The following article is an overview of the career of French pianist, composer, and arranger Alain Goraguer. The main source of information is an interview with Mr Goraguer, conducted by Bas Tukker in Paris, May 2011. The article, a rewritten version created in January 2023, is subdivided in two main parts; a general career overview (part 3) and a part dedicated to Alain Goraguer's Eurovision involvement (part 4).

All material below: © Bas Tukker / 2011 & 2023

Contents

- Passport

- Short Eurovision record

- Biography

- Eurovision Song Contest

- Other artists about Alain Goraguer

- Eurovision involvement year by year

- Sources & links

PASSPORT

Born: August 20th, 1931, Rosny-sous-Bois, Greater Paris (France)

Died: February 13th, 2023, Paris (France)

Nationality: French

SHORT EUROVISION RECORD

French arranger Alain Goraguer has a quite peculiar Eurovision record, having conducted five entries for three different countries, spanning a staggering 29 years (1965-94). His first involvement came in 1965, when his arrangement to Serge Gainsbourg's composition ‘Poupée de cire, poupée de son’ helped France Gall win the contest for Luxembourg. Subsequently, Goraguer led the orchestra for songs performed by Tereza Kesovija (Monaco 1966), Isabelle Aubret (France 1968), Joël Prévost (France 1978), and Nina Morato (France 1994). Moreover, he penned the arrangements to six more entries in the 1960s and 1970s, for which the orchestra was placed under the baton of other conductors.

BIOGRAPHY

Alain Goraguer was born in a Parisian suburb, but his youth was spent in places as far apart as Boulogne-sur-Mer, Lyons, and Nice. This was due to his father’s work for France’s National Police service.

“He was an officier de gendarmerie,” Goraguer explains, “and he was regularly moved from one post to another. This was common practice in the police services. My mother, who originated from Corsica, was an artistically minded woman. She was a good amateur pianist and singer. One day, when I was about ten years old, my parents took me to a concert in which a little girl performed a violin solo. This was while we were living in Lyons. The girl must have been about my age; she was absolutely beautiful and her violin playing was marvellous. The audience loved her, and so did I. Until that time, I hadn’t been particularly interested in music, but that one concert changed that. “I want to learn to play the violin as well,” I told my parents; and I insisted.”

“They then sent me to a violin teacher, and simultaneously my mother helped me on my way playing the piano. There was a piano in our house – and thanks to those violin lessons, I knew how to read notes. I just sat down and played a bit. Somehow, I was attracted to playing jazz; of course, during the war, jazz music wasn’t really acceptable, but that was no real problem for me, because I didn’t perform. All of this took place within the walls of our house; and only during the weekends, because my parents decided to send me to boarding school, which I wasn’t really happy with. Otherwise, I didn’t really suffer too much during the war years.”

Alain in his early 20s

“Slowly, I was less and less attracted to the violin; and more and more to the piano. Annoyed that I neglected the violin, my mother told the teacher about it. She was surprised to find that he hadn’t noticed a thing. “He’s an excellent student and I’m very happy about his progress.” This means that I must have had a bit of talent, because I hardly practised at all. As mother wasn’t keen to spend money on lessons I didn’t put much energy in, she told me I had to choose between the violin and the piano – and of course I chose the piano. I started taking piano lessons with a very good local teacher whose background was purely classical. As for the violin, je ne le touchais plus – I’ve never played it again for the rest of my life.”

“By the end of the war, my father had reached the pensionable age – and he decided he wanted to spend the remainder of his years on the French Riviera. We moved to Nice (which had just become French territory again after being occupied by Mussolini in 1940 – BT). After the liberation of that part of France, there were American seamen who regularly went ashore in the evenings to visit the local nightclubs and cafés. There were plenty of those in the port district. With some friends, I formed a little jazz group and we played in these cafés to entertain the Americans. Apart from the odd piano recital I had done at school, it was the first time I performed for an audience."

"It struck me that every American sailor was able to sing just about all jazz standards. Mind you, these aren’t easy songs to sing, but these guys were really very good at it. Somehow, the Americans are a musically gifted nation. With my friends, I played in all those clubs. The café owners didn’t pay us, but we didn’t really mind, because we loved playing; and besides, each night we went home with our pockets filled with tips the American guys had given us.”

“In Nice, I had the good fortune of meeting Jack Diéval, who was one of the greatest jazz pianists of his generation; really a grande vedette. I must have been 15 or 16, when my best friend had heard that Diéval was performing at various venues on the French Riviera at the time – and because this friend of mine was from a rich family, he managed to persuade his father to invite Diéval to their house for a lavish dinner! I was at the table as well, and this friend of mine introduced me to Diéval; “Monsieur Diéval, I would like you to meet Alain Goraguer. He is a friend of mine and he plays some great jazz piano.” Diéval was interested and asked me to play some pieces at the piano; and his reaction was absolutely wonderful. He said that I showed much promise; and he advised me to come to Paris, where he would introduce me to a piano teacher who could help me. This was great, because by that time I knew I didn’t want to go to university. I wanted music and nothing else! Fortunately, my parents didn’t object – and so I moved to Paris. That was in 1949.”

'Go-Go' with Boris Vian

“In Paris, Diéval introduced me to a classical piano teacher called Raoul Gola. He became my private teacher. In parallel, I also took music theory lessons with Julien Falk – studying fugue, counterpoint, and harmony. Both Gola and Falk were excellent teachers with an open eye to jazz. I owe Jack Diéval a lot for bringing me in touch with them. For the next four years, I was absorbed by my studies. I didn’t perform in groups or in jazz clubs – nothing of the sort. My parents supported me all the way, paying for all my expenses. This allowed me to live full board at a lodging-house.”

“For all those four years, I was a private student. I never studied at the conservatoire – although I spent one day at the Conservatoire de Paris. Julien Falk had recommended me to a piano teacher at the academy. There I was in her class, surrounded by boys who were about half my age, who performed all kinds of virtuoso exercises on the piano; I thought of myself as quite a good pianist, but I couldn’t keep up with them at all. After the lesson, the teacher asked me what my goals were. When I told her I wanted to become a professional musician, she exclaimed, “But you don’t have the required level at all!” When I explained her that I was mainly interested in playing jazz, she told me, “Well, in that case you won’t need me!” I always knew I didn’t want to be a concert pianist. At the time, the music which Gola put in front of me was quite complicated – and I loved those classical pieces, but jazz always was my passion. From that one day at the conservatoire onwards, I knew that I should forget about classical music and focus on jazz if I wanted to earn myself a living as a musician.”

“In 1953, I performed as a music professional for the first time. It was with a lady singer, Simone Alma. She sang French repertoire, but it included lots of jazz pieces which had been translated from English to French. Simone adored jazz. She didn’t perform that much – and when she performed, it wasn’t always in Paris. I became the piano-accompanist for her Parisian performances. She didn’t have a group of accompanying musicians; I was alone. Actually, I never performed as a musician in an orchestra. Why? Well, the opportunity never arose, but I don’t know if I would have been that keen. The atmosphere among jazz musicians usually wasn’t very good; people were jealous and hated each other. I didn’t like the jazz scene in Paris – and it is my impression that nothing much has changed ever since. The only time ever I performed solo as a jazz musician was around the time I met Simone Alma. I took part in a jazz piano contest and finished second – behind a young man called René Urtreger, who went on to have a fantastic career as a pianist. He even got to perform with Miles Davis.”

“Simone was always on the look-out for good new repertoire; songs which were a bit jazzy. One day she said, “Come with me to Boris Vian to see if he has got some songs for me.” Boris Vian was very much part of Paris’ literary scene and he wrote poems – but had started composing songs as well. At Boris’ house, I accompanied Simone at the piano while she was trying out songs he had in mind for her. Boris and I were immediately drawn to each other. He was a jazz man like me and we found we had a similar sense of humour. We exchanged phone numbers, and before long he called me back. By that time, Boris was performing as a singer himself with pianist Jimmy Walter, but Jimmy was also much in demand as a session musician. He wasn’t always available to work with Boris. Boris wondered if I would like to replace Jimmy now and again. After about a year, Jimmy Walter decided to focus exclusively on his studio work – and from that moment on, I became Boris’ regular piano-accompanist.”

During a recording session with Magali Noël and Boris Vian (mid-1950s)

“In his lyrics, Boris was an anti-establishment figure through and through. Jacques Canetti, the boss of record label Philips, allowed him to do whatever he liked. The lyrics of his chansons were never discussed; and I think Canetti pretty well understood that Boris wouldn’t have tolerated any interference. You shouldn’t think of Boris Vian as a politically engaged person; he was an anarchist, and by nature all anarchists are anti-political. Not even ‘Le déserteur’ (Vian’s best-known title, in which he vehemently critisises France’s involvement in colonial warfare – BT) is about politics – it’s an anti-war song."

"When Boris did a tour de chant, this was the only song which could be problematic. One night, while we were performing in Brittany, the Mayor of Dinard took offence at the lyrics and climbed on stage to drag Boris off. For a moment, it looked as if it would turn into a brawl, because Boris clenched his fists while still continuing his performance – and he sang ‘Le déserteur’ until the last line while this angry mayor was standing threateningly close to him. It was a sorry affair and I was happy to get away unscathed from the stage. Boris was braver than me, but at some point he stopped touring altogether. He was always someone with terrible stage-fright – and because he was suffering from heart problems, his doctors dissuaded him from working on stage.”

“My involvement with Boris continued, though, because we wrote quite a lot of songs together, some of which were recorded by Boris himself. I had never written songs before getting together with Boris, but he gave me the inspiration. Most of the time, I wrote a melody first which I brought to his attention – and then he usually came up with an idea for the lyrics very quickly. You may have heard of ‘La java des bombes atomiques’, which among the songs I wrote for Boris is probably the one which is best remembered today. We were also asked by others to write chansons for them, but first and foremost we composed because we liked to – and really to have a good time. There was always something unorganised and makeshift about my collaboration with Boris – it wasn’t my kind of approach to think along commercial lines, nor was it Boris’; and perhaps it was because this wasn’t the way of thinking of that age, if I may say so.”

“At the time, I wasn’t an arranger yet – and when Boris’ songs were recorded, he worked with Claude Bolling, Jimmy Walter, or André Popp. There’s one exception though, which is the song ‘Fais-moi mal Johnny’, which Boris and I wrote for Magali Noël, a great girl really and a gifted singer. It was an early attempt at rock ‘n’ roll and there wasn’t really much need to have a large orchestra backing her up; so I wrote a small arrangement as well as playing the piano. Boris himself made up part of the backing vocals on the spot, while we were already recording. It just goes to show how much we loved what we were doing.”

Goraguer released an instrumental solo record using the (female) pseudonym Laura Fontaine (1958)

“After he stopped performing, Boris became a producer at Philips – and he gave me the opportunity to record an instrumental album of American standards. It wasn’t recorded with an orchestra, but with me playing the piano backed up by bass and drums – simply a jazz trio. Boris came up with the idea of giving the record the title ‘Go-go-Goraguer’. From that time on, I was nicknamed Go-Go by many colleagues. One or two years later, I did another jazz album using the pseudonym Laura Fontaine. This was an idea which one of my friends at the Fontana record label came up with. The record company wanted to market the record as having been recorded in London by a lady-pianist – in those days, everything fashionable in music came from England. Of course, it was a marketing trick, because everything was recorded in Paris and the pianist was simply me. The record sold pretty well, until the imbecile who called himself artistic director at Fontana dropped the message in the press that Laura Fontaine was a fiction and that in reality she was a French pianist by the name of Alain Goraguer – and you know what, the record sales plummeted from that moment on. It was unfortunate to say the least.”

“By the time of Boris’ death in 1959, we didn’t really see each other very often, not because we had fallen out, but because I had become heavily involved in all kinds of studio work for Philips, which took up much of my time. The last thing I did was writing the music to the film J’irai cracher sur vos tombes (marketed in America as ‘I Spit On Your Graves’ – BT), which was based on a novel by Boris – but the film was produced without his involvement. Unfortunately it was very bad and didn’t have any success; and although Boris had told me how delighted he was with my jazzy soundtrack, he naturally was unhappy about the film itself; and in fact, at the premiere he had a heart-attack which caused his death.”

“Not counting those few rock recordings with Magali Noël, the start of my arranging career was with Serge Gainsbourg. I first got to work with him in 1958 when he had just signed his first record deal with Philips. Like with Boris Vian, I got on well with him straightaway – and we quickly became friends. For his first album, which included the song ‘Du jazz dans le ravin’, I created an atmosphere as if he was performing in a nightclub accompanied by a small combo. This surely was an innovation in terms of record arrangements in this country – adding a jazz feel to chansons. No other arranger had ever tried this. I did several more records with Serge, and the approach to the arrangements always remained more or less the same. At his request, I also composed the odd song for him.”

“When Serge was commissioned to write the music to the film L’eau à la bouche, he asked me to help. In reality, we composed the music together. Because the commission had been given to Serge, the two of us made an agreement to sign the music together as far as publishing rights were concerned, but to allow Serge to only have his name mentioned in the credits shown on screen. It was very important for Serge’s career as a film composer and, being his friend, I was happy to help him on the way. After L’eau à la bouche, we wrote the soundtracks to two more films on the same basis, but in the end we clashed. At the avant-première of our third film Strip-Tease (in 1963 – BT), Serge spoke to an audience of journalists and other professionals about his work as the film’s composer without mentioning my name – and not even crediting me for arranging or conducting the soundtrack. I was hurt. The following morning, I called him; in the end, he apologised, but I told him I had had enough. He couldn’t believe it, but I just couldn’t take being treated so disdainfully.”

Goraguer (second from left) in the recording studio surrounded by three other greats of French music - Serge Gainsbourg, Jacques Brel, and Michel Legrand (1960)

“Because there was a contractual obligation which had to be honoured, I did one more studio album with him, but from that moment on we only worked together indirectly, when he composed a song for an artist for whom I did the arrangements, like France Gall and Isabelle Aubret. Before breaking up with Serge, I advised him to consider choosing Michel Colombier as his new working partner. Colombier was a promising young pianist and arranger who was at ease as a record arranger as well as in film music – and he took my advice. For the next few years, he worked with Colombier on practically all his projects. In spite of what had happened, every time I met Serge after our break-up, it was as if we had never parted. Our friendship didn’t really suffer.”

“In 1960, Gérard Meys introduced me to Jean Ferrat. Gérard was Jean’s publisher and he invited the both of us to his office for a first meeting. Jean was a young singer-songwriter looking for an arranger. From that first encounter onwards, we got on extremely well. Probably because I was staff arranger at Philips at the time, I used the pseudonym Milton Lewis for the first record I did with Jean – because Jean was under contract with Decca! When I turned freelance some years later, those problems evaporated and I signed all subsequent arrangements using my own name. I found that Jean wrote excellent songs… ‘Nuit et brouillard’ perhaps being my favourite, although ‘Potemkine’ and ‘La montagne’ are masterpieces as well. As for my arrangements, I think I prefer ‘Raconte-moi la mer’, which isn’t among the best-known songs in Jean’s repertoire… but that is a score that could work independently as an instrumental piece as well. I’m rather proud of that one.”

“Although Jean Ferrat had a feeling for melody which was excellent, he wasn’t an accomplished musician on a technical level. He never studied music. Jean’s compositions weren’t finished products. He recorded me demos on which he accompanied himself playing the guitar, but he wasn’t able to bring about the tone shifts between the various parts of a given song. It was my job to more or less finish his compositions myself based on Jean’s template. In many of Jean’s songs, I added counter-melodies which became an integral part of the composition. Each time we started working on a new album, the two of us would meet at Gérard Meys’ office; together, we discussed what we had in mind for the songs – but there was little discussion, as Jean put complete trust in me. If I called him about some idea which hadn’t been on the table before, he just said, “You do as you want!” The recording sessions were easy; I don’t recall there was ever a problem.”

All in all, the partnership between Jean Ferrat and Alain Goraguer lasted for a staggering 35 (!) years (1960-95), in which Ferrat recorded 17 albums with Goraguer’s arrangements. Excluding some film compositions, for which Ferrat worked with other arrangers because Goraguer refused the commissions after his negative experiences with Serge Gainsbourg, the singer-songwriter always remained faithful to him. Throughout his life, Jean Ferrat made no secret of his political views, always remaining a staunch supporter of the ideals of communism.

One of countless Jean Ferrat releases arranged and conducted by Alain Goraguer, the 1964 EP 'C'est beau la vie'

When asked if he took offence at Ferrat’s extreme standpoints, Goraguer explains, “Well, admittedly, I would say I’m on the moderate right of the political spectrum, so I never really sympathised with Jean’s opinions, but there’s one important thing which should be explained when speaking about Ferrat’s communism – he never actually joined the French Communist Party. This allowed him to remain free and independent on an artistic level."

"I remember one song of his in which he expressed heavy criticism of the leader of the party, Georges Marchais (the song is ‘Le Bilan’ from 1980, in which Ferrat denounces Marchais’ loyalty to the Soviet regime in spite of the many crimes it committed – BT). For this I respected him. Having said that, we never discussed politics. Our conversation was always about music and music alone. Character-wise, Jean was a most charming man. I respected him; and the respect was mutual. Throughout these many years of working together, personal relations between us always remained excellent. This is one of the explanations for this unique partnership between an artist and a conductor; I for one have never heard of a track record in the world of music which comes even close to ours.”

“After having worked with Vian and Gainsbourg, I never had to go looking for new commissions. The successful records with Jean Ferrat made things even easier. I wouldn’t dare to say that my work from then on bore a stamp of quality, but at least it was written by someone who had a reputation in the business. For the next 15 years or so, I wrote arrangements for dozens and dozens of artists (in fact, Serge Elhaïk’s bible of French arrangers includes an – incomplete – list of 176 (!) artists who recorded their work with Alain Goraguer’s orchestra – BT). Because I was so sought-after as an arranger, there was little time to compose my own music. In the early days, I composed a couple of songs here and there, but I had to completely stop doing that, simply because there are no more than 24 hours in a day!”

“Asking me how long it took me on average to write a song arrangement is really an impossible question to answer. Sometimes, I have the inspiration to write the chart on the spot, but on some other occasions it’s hard work finding the correct approach. Each arranger has his own way of working; mine has always been to make drafts, writing down some ideas here and there, crossing out some of those after a second look, before finding a synthesis – it’s like writing the final version of a letter after having made notes on a scrap paper to order your thoughts. It also makes a big difference if you’re working with a songwriter who brings a written score, like Michel Legrand, an accomplished musician in his own right – if you were willing to examine it closely, the arrangement was already in it, so to speak… but in the case of many others, I had to work from demo tapes, which took more time and effort.”

Goraguer (second from left) in Studio Barclay-Hoche with (from left) sound engineer Claude Achallé, Marielle Braun (assistant manager at this Parisian recording studio), Jean Ferrat, and a second sound engineer, Philippe Omnès (mid-1970s)

“Hits? You’re asking me if I remember hit songs I arranged? Well, there must have been some successes here and there, because I wrote thousands of arrangements! Yes, I recall ‘Le métèque’ for Georges Moustaki, but that was just some strings which had to be added at the back… personally, I prefer a song like ‘Cent mille chansons’ for Frida Boccara. I adore it. I like to think that I gave it a distinct colour with a classically oriented string arrangement; but even for such a ballad, I’ve always loved adding some rhythmic elements, which perhaps is typical of my style of writing.”

“This classical cross-over approach also worked well for Nana Mouskouri. I worked with her for many years. She’s also one of the few artists with whom I also performed on stage. When the Montreal Symphony Orchestra in Canada celebrated its 50th anniversary (in 1980 – BT), Nana was invited to do a programme with them. I didn’t conduct the concert, but played the piano in the orchestra. It was a wonderful occasion and we were very well received. On stage, I also worked with Adamo at the Olympia and with Jean Ferrat in the Palais des Sports. I never went on tour with any artist. It wouldn’t have been possible. The studio work was simply too important to stay away from Paris for too long.”

“In the second half of the 1970s and beyond, I continued to work with artists like Isabelle Aubret, Nana Mouskouri, and of course with Ferrat, but by this time my main field of work had become writing film soundtracks. After J’irai cracher sur vos tombes and the films with Serge Gainsbourg, I became more and more in demand as a film composer. Producers were aware that I knew how to write film music. The fact that I had arranged music for artists in all imaginable different styles and genres helped me a lot as a film composer. Just an example… when there is a movie scene which takes place in a circus, you have to know how to write circus music. You have to be versatile and able to adapt to any given atmosphere. For a musician, working on films is definitely more interesting than arranging pop songs. As a studio arranger, your possibilities to write are limited by the lyrics and the vocal possibilities of the artist you’re working with. Film music gives you more freedom – the freedom to use an orchestra in any given way. There’s more creativity involved.”

From the late 1950s onwards, Alain Goraguer wrote the soundtracks to just under 100 films. Among the best-known titles are the comedy Perched On A Tree with Louis de Funès (1971), the crime drama The Dominici Affair with Jean Gabin (1973), and René Laloux’s animated science-fiction film Fantastic Planet (1973), which won several film prizes in France and abroad. Using his pseudonym Paul Vernon, Goraguer also wrote the music to erotic movies. In the world of television, he made his mark in the 1980s by composing the jingles and incidental music for various broadcasts, most notably the successful fitness programme Gym Tonic and the long-running German drama series Ein Heim für Tiere (ZDF). In 2006, the intro music for Gym Tonic was re-used for a TV commercial by a French telephone company – and the song was also remixed by various DJs.

Goraguer with lyricist and friend Claude Lemesle at the premiere of their musical 'Mademoiselle bonsoir' (2009)

When asked about the evolution of the studio business, Goraguer comments, “Pop music has seen an evolution which I think is sad. Electronic instruments took over the place of studio orchestras; and, even before that, opportunities to write orchestrations with a distinct character became fewer and fewer, simply because it wasn’t what producers were looking for any longer. Today, artists record their songs in home studios. Fortunately I always had my soundtracks to work on. There was never a question of being out of work. Of course I don’t take on as much workload as in the old days, but I’ve never stopped writing.”

“Recently (in 2008 – BT), I wrote the music to a film, Love Me No More, for which the director asked me because he loved my arrangement to ‘Le temps qui reste’, which was one of the last songs recorded by Serge Reggiani before he passed away. This director wanted me to write a soundtrack based on the harmonies in that song. I composed it working with my son Patrick, who studied at Berklee College of Music in Boston. The following year, the two of us teamed up again to compose a musical based on a script which Boris Vian wrote but never managed to finish because of his untimely death. The lyrics were done by my old friend Claude Lemesle. Its title was ‘Mademoiselle bonsoir’. That was another honourable commission.”

“A project which I enjoyed working on was the album ‘Dante’ with a hiphop artist, Abd Al Malik (also in 2008 – BT). I was contacted about this project by Malik’s producer. As it turned out, he had five songs for his new album written by Gérard Jouannest, who used to be Jacques Brel’s accordionist. When we met, I was surprised to find that Malik had detailed knowledge of me and my work in the world of French chanson. At his request, I wrote the arrangements to those five pieces by Gérard. As there was a considerable budget available, I worked with a large string orchestra – and it worked wonderfully well. Everything was recorded completely live; something which is rarely ever done in the world of studio music these days. One of the titles on that album, ‘Roméo et Juliette’, was recorded as a duet between Malik and Gérard’s wife Juliette Gréco. After the recording sessions were over, Malik told me, “I dreamt of this; it was exactly what I had in mind!”

Reflecting on his remarkable career as a studio arranger, Goraguer concludes, “I’ve always been of the opinion that it’s impossible to teach someone to write arrangements. I was never educated to arrange. Of course I studied harmony and counterpoint, which I would say are the grammar and orthography in language… in other words, a solid base from which you can work to learn your craft. From that moment on, if it turns out you’re able to write arrangements, I think of that as a gift from above. Some will never learn it, others find they have a talent for it. I’ve been fortunate enough that I possess that one gift. One time, a colleague in the business told me he had been asked by a record company to write the strings in the way that Goraguer did. When I took the time to think of those words, I realised that I could hardly think of a better compliment than that!”

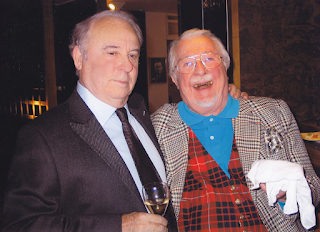

With the man who stood at the cradle of his career, jazz pianist Jack Diéval (2009)

EUROVISION SONG CONTEST

In the Eurovision Song Contest, Alain Goraguer conducted five entries for three different countries between 1965 and 1994. His debut involvement was with the song representing Luxembourg at the contest held in Naples in 1965, which won first prize and has become one of the trademark melodies in festival history; ‘Poupée de cire, poupée de son’. It was composed by Serge Gainsbourg and performed by 17-year-old France Gall. Not least owing to Goraguer’s striking arrangement of string and percussion, this song stood out from the crowd. When asked about this involvement, Goraguer just shrugs his shoulders.

“Writing the arrangement to this thing did not take me long; as so often, I sat at the piano and the idea came to me within a couple of minutes. The intro I wrote was based on a classical theme, which was quite innovative – not that I was consciously writing modern arrangements… it is just a part of my character to explore new ways. Musically speaking, I try to avoid trodden paths. With hindsight, the way in which I treated the strings, but actually the entire arrangement of ‘Poupée de cire’, was somewhat revolutionary. The loud percussion gave it a lot of dynamism. It was a totally different approach than the usual Eurovision orchestrations as Franck Pourcel and others used to write them in those days. Gainsbourg had had no input in the arrangement. It was thought up by me and me alone."

"I already knew France Gall long before the contest – actually, I met her before I first met Serge Gainsbourg in 1958! She was the daughter of Robert Gall, an important songwriter and music publisher. He was one of the big beasts in the business here in France; did you know he wrote the lyrics to ‘La Mamma’ for Charles Aznavour? France Gall started recording when she was fifteen – and I was her arranger from the beginning. Because everything coming from England was deemed fashionable at the time, I signed the arrangements for her using the English pseudonym Milton Lewis. France was a fantastic girl with a heart of gold; and she was a talented singer. Working with her was always a pleasure.”

“The rehearsals with the orchestra in Italy were fine. Especially the rhythm section did a good job. They gave us exactly what we were looking for. I don’t remember those days in Naples in detail, but I certainly wasn’t nervous to conduct the orchestra in Eurovision. I can’t remember ever being nervous in front of a group of musicians. I never took any conducting classes, but somehow I always managed without problems. It’s not that difficult actually. You require a minimum of technique – how to count in an orchestra, things like that… but from that point on, each conductor develops his own style, no matter if he works in the field of classical music or in entertainment."

France Gall during her winning Eurovision performance in Naples (1965)

"Like most of my colleagues, I began my learning process by watching other conductors at work in the recording studio. Once I started recording my own arrangements, I simply stood up and did it. Musicians have always told me that my movements and gestures are clear; there was never any problem. In fact, I’ve always loved conducting, especially when I was working with a string orchestra. When they’re playing well, a group of string players more or less becomes one musician with just one instrument; as if one person is playing it.”

“When we won the festival in Naples, Serge Gainsbourg was beside himself with joy. He had had to struggle for years for recognition in France. His first solo albums didn’t sell well at all. There were moments he was feeling desperate. Having such a major success in mainstream music on an international podium was great for him. It was the biggest triumph in his career up to that point. In those first difficult years of his career, I had been Serge’s arranger, but by the time of the contest in Naples, we hadn’t worked together regularly for some time. The Eurovision commission came my way because I was France Gall’s regular arranger. I had had my issues with Serge in the past, but in those moments of intense joy, everything from the past was forgotten. After we won it, Serge told me how happy he was that I had written the orchestration. For me personally, the 1965 contest was an important moment as well. Your name is mentioned a second time for the reprise of the song. First and foremost, it meant recognition for your work; not just in your own country, but Europe-wide recognition.”

“Commercially, it was a good moment as well, because France Gall had a big international hit with her Eurovision song. In those years, I composed some jazzy tunes for her. One of those (‘Le cœur qui jazze’ – BT) was released on the EP of ‘Poupée de cire, poupée de son’ – and as copies were on sale across Europe, it earned me a considerable amount of revenues. I was never in the business to earn lots of money, but of course I didn’t walk away from it once it came my way. I continued to work with France Gall for some more years until she chose a different career path with songs composed by Michel Berger, which I thought were really good too. The last time I worked with her was for a children’s record entitled ‘Sacré Charlemagne’” (in 1976 – BT).

Luxembourg's winning Eurovision team proudly sporting their winner medals - Serge Gainsbourg, France Gall, and Alain Goraguer

In 1966, when the contest was held in Luxembourg as a result of France Gall’s win the year before, Alain Goraguer conducted the Monegasque entry, ‘Bien plus fort’, composed by Gérard Bourgeois and Jean Max Rivière; and interpreted by Croatian songstress Tereza Kesovija, who was trying to build an international career. In a complete reversal of fortune for Goraguer, the song did not receive a single point and finished at the bottom of the scoreboard.

“Of course, it was never a pleasant experience when a song you had worked on as an arranger and conductor did badly in the voting,” Goraguer readily admits, “but, frankly speaking, a conductor had little to lose; from personal experience, I can say that, while winning the Eurovision Song Contest had a positive impact on your career, a bad result hardly affected it at all. For a singer, this is a totally different story. Tereza sang well; the problem was her song. It didn’t suit her vocal abilities at all. Putting it mildly, I would say it doesn’t rank among the better songs written by Bourgeois and Rivière.”

In the 1966 contest, Goraguer had a second iron in the fire, given that the Swiss entry, ‘Ne vois-tu pas’, performed by Madeleine Pascal, was also arranged by him. Oddly, in the contest itself, the song wasn’t conducted by Goraguer, but by Luxembourg’s resident conductor Jean Roderes.

“Yes, that’s quite odd, because I was there to conduct the orchestra for Tereza. Did I really arrange that song? I don’t remember it, but from my mouth those words don’t count for much. In the mid-1960s, I was overburdened with arranging work; I wrote hundreds and hundreds of scores, for dozens of artists. You cannot expect me to remember all of them, can you? Probably Swiss television decided they wanted to use the home conductor in Luxembourg. Perhaps they didn’t want to pay me for conducting their entry on television? Who knows. I’m afraid I can’t solve this mystery for you.”

Croatian songstress Tereza Kesovija performing 'Bien plus fort' as Monaco's representative in the 1966 Eurovision Song Contest in Luxembourg

In the 1968 Eurovision Song Contest, held in London’s Royal Albert Hall, the exact same situation occurred as two years before. Goraguer himself was present to conduct the French entry, performed by Isabelle Aubret. One of her fellow-competitors was Czech crooner Karel Gott, who represented Austria with ‘Tausend Fenster’, a song also arranged by Goraguer. This song, composed by Udo Jürgens, was recorded in Vienna, though, with the studio orchestra conducted by Robert Opratko, who also accompanied Gott on the festival stage in London. Although Goraguer himself didn’t remember this involvement, it seems logical that he was asked to work on the arrangement at the request of Udo Jürgens himself. In 1968, the year of the contest, Jürgens released a solo album co-arranged by Opratko and Goraguer. The first meeting between Goraguer and Jürgens might have taken place in Luxembourg two years previously, when the Austrian singer won the Eurovision Song Contest with ‘Merci chérie’.

When asked about ‘Tausend Fenster’, Austrian conductor Robert Opratko recalls, “I was asked by Udo Jürgens to conduct the song. The arrangement was ready and done – I only had to conduct it. Udo organised all of that. My contribution was just to conduct it in the studio and on the festival stage in London. It was the first time I got to work with Karel Gott, with whom I’ve remained friends all my life. It was unfortunate we finished near the bottom, but fortunately it didn’t really harm Karel’s career.”

The fact that Goraguer got to conduct the French entry is noteworthy, given that France’s conductor in the previous ten – and the following four – editions of the festival had always been Franck Pourcel, irrespective who the arranger of the song was. In London, Isabelle Aubret, who had won the 1962 contest with ‘Un premier amour’, finished third with the wonderfully understated and slightly folk-oriented ballad ‘La source’. When asked about the involvement of Goraguer as a conductor in the 1968 Eurovision Song Contest, Isabelle Aubret’s husband and manager Gérard Meys confirmed, “Because Alain had written the arrangements to ‘La source’, Isabelle and I wished to have him accompanying her for the contest in London as well.”

“Yes, in those days artists going to Eurovision for France were more or less obliged to work with Pourcel,” Goraguer comments. “Gérard and Isabel must really have pressed TV authorities about the matter, but I wasn’t involved in that myself. Gérard and I knew each other well due to our mutual involvement with Jean Ferrat. In parallel with Jean Ferrat, I wrote arrangements for Isabelle too. The Eurovision Song Contest wasn’t my first involvement with her. I was her regular arranger at the time – and we had a close working relationship which lasted for many years. She was a very artistic and pleasant person and, more importantly, a really good singer. ‘La source’ was brilliant in its simplicity, with great lyrics done by Henri Djian and Guy Bonnet. I decided to keep the arrangement sober, simply following the music."

"I remember the contest with Isabelle quite well. The Royal Albert Hall was a magnificent theatre. The English are very good at organising such an event. I distinctly remember one of the other delegations arriving late for their rehearsal. They arrived five minutes before the end of the rehearsing time allotted to them; and they were told that there was nothing that could be done about it. The artists apologised, but were indignant too. They tried to talk the show’s producer into giving them some extra time, but he said he could not change the schedule just for them. He was right in doing so and I really liked his attitude. In fact I recall being rather amused.”

Isabelle Aubret rehearsing her performance of 'La source' on the Eurovision stage in London's Royal Albert Hall with Alain Goraguer (in light blazer, left from middle) conducting the orchestra

“I didn’t really try to meet other participants in the contest. Usually, at such an event, you simply stuck with your own delegation. I remember being really happy with the performance of the English musicians. As you would expect from the English, they had assembled a fine orchestra. When we came third, Isabelle was bitterly disappointed. Because she had won the contest before and as she was a true winner by character, she was reduced to tears after the voting.”

Goraguer also penned the score to the French entry the following year, Frida Boccara’s Eurovision winner ‘Un jour, un enfant’ (1969), but this time he had to cede his place to the perennial Franck Pourcel. Even all those years later, Goraguer cannot hide his irritation when talking about Pourcel’s involvement in the Eurovision Song Contest.

“The truth is this; artists, who represented France, were obliged to have Pourcel as their conductor in those years. It was French television which wanted it that way. People in the business weren’t happy with Pourcel – and when I say ‘people in the business’, that includes myself. For the Eurovision Song Contest, he took the original orchestration which was written by me or another studio arranger, changed two or three notes and signed his name under it, claiming the arrangement as his. While my personal relationship with him was quite good, I thought his behaviour was shocking and scandalous. No, I never told him. It would have served no purpose, because he didn’t care what others thought of him. The man knew exactly what he was doing. It was very cynical, because it was only about money."

"‘Un jour, un enfant’ is a prime example. For the studio version, I wrote an arrangement of rhythm and strings only, in a style reminiscent of Frida’s hit ‘Cent mille chansons’. Then Franck Pourcel came along and added some brass elements. It was ridiculous, because these didn’t fit the song at all. Having made that tiny adaptation, he was paid all the money for the television performance; and I received nothing! I for one would have loved to do Eurovision with Frida Boccara, who was one of the artists I liked most on a personal level. The first time I worked with her, she invited me over to her place to discuss the songs and the arrangements. With her entire family, who were Jews from Northern Africa, she lived in two apartments in Paris’ 15th arrondissement. Her mother and all the others were extremely friendly. The atmosphere there was wonderful. I feel privileged having worked with Frida for some years; she was a great singer.”

Frida Boccara performing her Eurovision winner 'Un jour, un enfant' on the festival stage in Madrid (1969)

With ‘Un jour, un enfant’, Goraguer had his second involvement in a Eurovision win, though the events left him with a bitter taste in his mouth. Perhaps Pourcel did take notice, though, because for the 1970 and 1972 French entries, ‘Marie Blanche’ by Guy Bonnet and ‘Comé-comédie’ by Betty Mars, both arranged by Alain Goraguer again, he seems to have left the original arrangement unchanged. Goraguer also had a hand in the Belgian entry in 1970, ‘Viens l’oublier’, which was performed by Jean Vallée – and conducted by RTB’s musical director at the time, Jack Say.

“Jean Vallée was a great artist,” Goraguer comments. “He sang really well. Betty Mars is another artist who I would have loved to go to Eurovision with. I also arranged her first hit, ‘Monsieur l’étranger’. Her songwriter was Frédéric Botton, a guy who wrote a lot of music – I recorded dozens of his compositions. The outstanding memory I have of Betty is that she behaved like a tomboy; and that her entourage was a bit on the wild side. She was a really beautiful girl with a remarkable voice. It’s sad that she died so young.”

Excluding his involvement as an arranger and conductor in the 1976 French Eurovision pre-selection with Isabelle Aubret and ‘Je te connais déjà’ (composed for her by Jean Ferrat), Alain Goraguer’s next participation in the festival came in 1978, when the contest was held in Paris and he conducted the French entry, a somewhat pompous ballad, ‘Il y aura toujours des violons’, performed by Joël Prévost. The song managed to pick up 119 points and finished third in a field of 20 competing entries.

“Joël was quite a talented guy,” Goraguer recalls. “Unfortunately, he never really used his talent to the full. Having a tendency to be overconfident, he usually prepared his performances in a way which I thought was a bit amateurish. He could have had a better career. Having said that, we were happy to finish third; it was a good result.”

“My outstanding memory of the contest in Paris is how chaotic the organisation was. The contests abroad which I took part in, were always organised to perfection. In Paris, even the orchestra (led by French television’s musical director François Rauber – BT) wasn’t very good. It also struck me how little respect was shown to the participants. There was an air of disinterest over the contest. As a conductor, I was left to my own devices. I wasn’t really surprised, because people in France have no respect whatsoever for conductors. I did studio sessions in England with Nana Mouskouri and in Belgium with Adamo. In Germany, I recorded music for television series. In Canada, where I performed with Nana Mouskouri, I was treated with the same amount of respect as Nana herself. When I came down the airplane ladder, people started asking me for autographs. They were able to name a whole range of records I had worked on. Wherever you go, be it in Europe or in America, they know who you are – but once you arrive home in France, you go back to being a nobody.”

In 1981, Alain Goraguer conducted two songs in the French Eurovision pre-selection; ‘Les yeux fermés’, a chanson composed by none other than Jean Ferrat and interpreted by Evelyne Geller; and ‘Voilà comment je t’aime’, penned by Eddy Marnay and Michel Jourdan, interpreted by Frida Boccara, but neither of these songs came close to winning the ticket to the international contest, which was awarded to Tahitian singer Jean Gabilou.

Thirteen years later, at the age of 62, Goraguer made a surprise return to the Eurovision Song Contest when he orchestrated and conducted the French entry in the 1994 festival held in Dublin, ‘Je suis un vrai garçon’. This unusual effort was composed by Bruno Maman and interpreted by Nina Morato. In Dublin, Morato finished seventh in a field of 25 competitors.

When asked how he became involved in a song of which both the composer and the performer are of a much younger generation, Goraguer explains, “Bruno Maman is about as old as my son Patrick. They were friends from their early childhood and both became professional musicians. In the 1990s, they worked together very often. Nina Morato was a mutual friend of theirs. Patrick gave Bruno the idea of asking me to write the strings to his song, which by then had been selected for Eurovision by French TV.”

Nina Morato representing France at the 1994 Eurovision Song Contest in Dublin with 'Je suis un vrai garçon'

“I thought the song itself was rigolo, very funny. I liked the fact that it was impossible to put a label on it. Nina’s choice of clothes and stage performance were special as well. Unfortunately, she was perhaps a bit too crazy to have a good career, but it was undeniable that she had talent. The same could be said of Bruno Maman. Years later, I arranged two solo albums of his (in 2005 and 2008 – BT), but they didn’t sell well at all, which I thought was a real pity. They deserved more attention than they actually got.”

"In Ireland, I wasn't really involved in the contest, apart from conducting the rehearsals and the concert. By character, I'm not that interested in socialising anyway, but in Dublin I simply didn’t have the the time to come along with the others even if I had wanted to. Apart from the hotel where we were staying, I saw nothing of the city. Two weeks after the contest, I was due to record a new studio album with Jean Ferrat with poems by Aragon (‘Ferrat 95’, incidentally also Jean Ferrat’s last album – BT). When I left for Dublin, the orchestrations weren't ready yet. I couldn’t afford interrupting my work on them for a whole week. The deadline was too sharp for that. I spent every possible moment in Ireland in my hotel room, writing scores. I was brought to the auditorium by taxi to conduct the rehearsals with the orchestra, did my job there, and got back into the taxi as fast as I could to be rushed back to the hotel. Of course the orchestra was fine, so there was never an issue."

"I do remember the broadcast, with Ireland winning with a simple, beautiful song by two guys with a piano and a guitar (Paul Harrington & Charlie McGettigan with ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Kids’ – BT). It was a brilliant piece of music – very artistic and intricate yet straightforward at the same time. The Irish have a way of writing those excellent ballads, because they won with equally beautiful songs in the two years before, didn’t they? Unfortunately, the Eurovision Song Contest has changed since those days. It doesn’t even resemble the event in which I took part in my time. I don’t think beautiful ballads like that could win the contest nowadays.”

OTHER ARTISTS ABOUT ALAIN GORAGUER

So far, we have not gathered comments of other artists who worked with Alain Goraguer.

EUROVISION INVOLVEMENT YEAR BY YEAR

Country – Luxembourg

Song title – "Poupée de cire, poupée de son"

Rendition – France Gall

Lyrics – Serge Gainsbourg

Composition – Serge Gainsbourg

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

(studio orchestra conducted by Alain Goraguer)

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Alain Goraguer

Score – 1st place (32 votes)

1966 Luxembourg (1)

Country – Switzerland

Song title – "Ne vois-tu pas"

Rendition – Madeleine Pascal

Lyrics – Roland Schweizer

Composition – Pierre Brenner

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

(studio orchestra conducted by Alain Goraguer)

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Jean Roderes (MD)

Score – 6th place (12 votes)

1966 Luxembourg (2)

Country – Monaco

Song title – "Bien plus fort"

Rendition – Tereza Kesovija

Lyrics – Jean-Max Rivière

Composition – Gérard Bourgeois

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

(studio orchestra conducted by Alain Goraguer)

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Alain Goraguer

Score – 17th place (0 votes)

1968 London (1)

Country – Austria

Song title – “Tausend Fenster”

Rendition – Karel Gott

Lyrics – Walter Brandin

Composition – Udo Jürgen Bockelmann (Udo Jürgens)

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

(studio orchestra conducted by Robert Opratko)

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Robert Opratko

Score – 13th place (2 votes)

1968 London (2)

Country – France

Song title – "La source"

Rendition – Isabelle Aubret

Lyrics – Guy Bonnet / Henri Djian

Composition – Daniel Faure

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

(studio orchestra conducted by Alain Goraguer)

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Alain Goraguer

Score – 3rd place (20 votes)

Country – France

Song title – "Un jour, un enfant"

Rendition – Frida Boccara

Lyrics – Eddie Marnay

Composition – Emile Stern

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

(studio orchestra conducted by Alain Goraguer)

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer / Franck Pourcel

Conductor – Franck Pourcel

Score – 1st place (18 votes)

1970 Amsterdam (1)

Country – Belgium

Song title – "Viens l’oublier"

Rendition – Jean Vallée

Lyrics – Jean Vallée

Composition – Jean Vallée

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Jack Say

Score – 8th place (5 votes)

1970 Amsterdam (2)

Country – France

Song title – "Marie Blanche"

Rendition – Guy Bonnet

Lyrics – Pierre-André Dousset

Composition – Guy Bonnet

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

(studio orchestra conducted by Alain Goraguer)

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Franck Pourcel

Score – 4th place (8 votes)

Country – France

Song title – "Comé-comédie"

Rendition – Betty Mars

Lyrics – Frédéric Botton

Composition – Frédéric Botton

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Franck Pourcel

Score – 11th place (81 votes)

Country – France

Song title – "Il y aura toujours des violons"

Rendition – Joël Prévost

Lyrics – Didier Barbelivien

Composition – Gérard Stern

Studio arrangement – Alain Goraguer

(studio orchestra conducted by Alain Goraguer)

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Alain Goraguer

Score – 3rd place (119 votes)

Country – France

Song title – "Je suis un vrai garçon"

Rendition – Nina Morato

Lyrics – Nina Morato

Composition – Bruno Maman

Studio arrangement – Bruno Maman / Jam’Ba (= Jean M'Ba) / Alain Goraguer

(studio orchestra conducted by Alain Goraguer)

Live orchestration – Alain Goraguer

Conductor – Alain Goraguer

Score – 7th place (74 votes)

SOURCES & LINKS

- Bas Tukker interviewed Alain Goraguer in Paris, August 2011; the interview as published above is a new, rewritten version from 2023

- Serge Elhaïk did an interview with Alain Goraguer as well for his magnificent and highly recommended book "Les arrangeurs de la chanson française", ed. Textuel: Paris 2018, pg. 963-976

- Thanks to Robert Opratko for his additional comments

- An impression of Alain Goraguer's music can be accessed by clicking this YouTube playlist

- Photos courtesy of Alain Goraguer & Ferry van der Zant

- Thanks to Mark Coupar for proofreading the manuscript

No comments:

Post a Comment