The following article is an overview of the career of Portuguese singer-songwriter, guitarist, and arranger Carlos Alberto Moniz. The main source of information is an interview with Mr Moniz, conducted by Bas Tukker in 2018. The article below is subdivided into two main parts; a general career overview (part 3) and a part dedicated to Carlos Alberto Moniz's Eurovision involvement (part 4).

All material below: © Bas Tukker / 2018

Contents

- Passport

- Short Eurovision record

- Biography

- Eurovision Song Contest

- Other artists about Carlos Alberto Moniz

- Eurovision involvement year by year

- Sources & links

PASSPORT

Born: August 2nd, 1948, Angra do Heroísmo, Terceira Island, Azores (Portugal)

Nationality: Portuguese

SHORT EUROVISION RECORD

Apart from his involvement as a performer, songwriter, arranger, and conductor in many editions of the Portuguese Eurovision pre-selection, Carlos Alberto Moniz orchestrated and conducted two Portuguese Eurovision entries, ‘Há sempre alguém’, performed by Nucha in 1990; and, two years later, ‘Amor d’água fresca’ by Dina.

BIOGRAPHY

Hailing from the Azorean archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, Carlos Alberto Moniz was born in 1948 on the island of Terceira. Though his ancestors do not include any music professionals, it was almost genetically destined that he became one.

“I didn't really have a choice”, Moniz laughs. “My granddad was a good amateur violinist. He wrote some small symphonies based on local Azorean folk music. My father was a bank clerk, but he had a passion for the piano. In the evenings, he played in a jazz big band which performed at the US Airbase on Terceira Island. All the greats of the American entertainment industry passed by to perform for the US military, including Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra; my father didn't even know who these guys he was accompanying really were at that time! Playing the piano in the weekends made him some extra money which was used to refurbish the family house here and there. Encouraged by my father, I started learning music with two music teachers. They were Raul Coelho and Manuel Arraial. I studied solfege and harmony, while I also practiced the piano and the violin. I never became a professional at either of these instruments, but, with hindsight, it was a useful learning school for a future arranger.”

At special festivities in the local seminary, Carlos Alberto played the violin in the Terceira Island Chamber Orchestra, but in the meantime, another music instrument had won his particular affection: the guitar, on which he mainly taught himself how to play.

When asked why the piano fell from grace, Moniz jokingly comments, “Because I couldn't carry a piano! On a serious note, I guess the guitar was better suited to the style of music I wanted to play. Though I've always loved classical music, I never had the ambition to go that direction myself. I was interested in Brazilian rhythms and, later on in the 1960s, The Beatles appeared on the scene. Someone who went on a holiday trip to London brought me a sheet music book of Beatles songs. I memorised all of them. With some high school friends, I formed a little band with which we played cover versions of pop songs from the UK and America. Years later, looking back on our teenage days, some of my fellow band members complained about how exigent I had been, demanding them to play all notes and chords exactly as on the Beatles records. Being a Beatles fan, I never became a follower of the Rolling Stones school of pop music. In any type of music, I prefer melody over power; even of the classical composers, I appreciate the qualities of Beethoven, but the romantic style of the likes of Ravel and Debussy is simply better suited to my ears.”

Carlos Alberto as a toddler with his grandfather, violinist and composer João Moniz, and his father, jazz pianist Alberto Moniz

Though his parents left him a free choice, Carlos Alberto could not imagine making a living as a music pro and instead chose a seemingly safer career path by studying engineering at Lisbon’s Superior Institute of Agronomics. In 1967, aged 19, he moved to Portugal’s capital.

“Under the Salazar regime, one of my uncles was the director of the Terceira Agronomic Station. He suggested to me to go to Lisbon and study engineering to come back after that and become his successor. That is the way you got a job back in those days – it sounds awful now, but back then I did not think it was a bad idea at all! From the start, I felt at ease in Lisbon. I soon made friends, especially at the students’ association of the Agronomics Institute, where the democrats would gather every week and invite a singer-songwriter for a performance. I was there all the time with my guitar on my knees, hoping that any of these artists would invite me to play along – and, one day, what I had hoped for actually happened. Performing at our students’ club was Adriano Correia de Oliveira, who approached me, “You are a kid from the islands, aren’t you? Well, tomorrow I am recording a studio album with Azorean music. Would you like to join me there?” This was my dream come true! So I came to the studio and played on this album. Coincidentally, José Afonso was in those same studios that day and invited me to travel to Madrid with him to record an album of protest songs. That is how my career as a musician kick-started. As you will understand, although I stayed at the institute for some 7 years, I never finished my agronomy studies…”

Throughout the 1970s, Moniz was the guitarist for stage performances of three of Portugal’s best-known troubadours; José Afonso, Adriano Correia de Oliveira, and Carlos Paredes. Logically, given the nature of the Estado Novo regime, it was not until the Carnation Revolution in 1974, when the Portuguese shook of the yoke of the authoritarian Estado Novo regime, that the careers of these left-wing protest singers really took off.

“I wouldn't say that is entirely true… Of course, the revolution was the moment when they became national icons, especially José Afonso – his song ‘Grândola, vila morena’ was played on the radio on the 25th April as the signal for revolutionaries to start their coup. It became the anthem of the revolution. But in the last years of the Estado Novo, when Caetano had taken over from Salazar, the regime’s policies had already been less oppressive. Caetano hoped it would be good for his reputation to open up some windows which had hitherto remained closed – and so Afonso and the others were allowed to perform, as long as they left the issue of the colonies and other sensitive political subjects alone. Their music would not be played on the radio, but Afonso’s albums, which were recorded abroad, were sold under the counter everywhere. So it wasn't only in 1974 that we showed up. The nucleus of left-wing artists in Portugal had already been there for years. After the revolution, there was a lot of political zeal among musicians in Portugal. I would say 90 percent of us were socialists or rather anti-fascists – myself included!”

Recording José Afonso’s 1974 album ‘Coro dos Tribunais’ at the Pye Studios, London, from left to right - Afonso himself, Fausto (guitar), Vitorino (keys), Michel Delaporte (percussion), and Carlos Alberto Moniz (guitar)

In the second half of the 1970s, Moniz toured extensively with Afonso, Correia de Oliveira, and Paredes, and not only in Portugal – in the wake of the Carnation Revolution, international interest in Portuguese folk music grew considerably. In 1975, Moniz joined ‘Zeca’ Afonso at the Festival of Political Songs, East Berlin. Two years later, he represented Portugal on the same stage, this time backing up Carlos Paredes, with whom, moreover, he also performed at the Intervision Song Contest in Sopot, Poland.

“We went absolutely everywhere in those years. One week, I was in Greece with Carlos Paredes; and the next month I would be with Zeca in Canada or Holland… I performed in over 20 countries. Considering how many high-profile invitations we received, you would be surprised at the improvised character of what we did on stage. I remember one time, performing with Zeca Afonso at the Fête d’Humanité in Paris, a grand occasion with big names… Mikis Theodorakis and Leonard Cohen; as we came on stage, my question to José simply was, “Zeca, what is the first title we are going to play?” When we went into the studio to record an album, we created the sound of most of the songs on the spot."

"Zeca was a great character who only knew a couple of chords to play on the guitar, but many of the melodies he created are fabulous. I worked with him for 6 or 7 years, though on and off. He taught me to be totally honest as a musician – if he sang a song about workers on the land, he would actually go out to the countryside to play for these men and women. Paredes, on the other hand, showed me the importance of humility. When we performed together, he always wanted his chair to be next to mine… he absolutely refused to be up front on his own. At Intervision, he simply drew his chair back during a live television performance, which caused considerable panic amongst sound technicians there!”

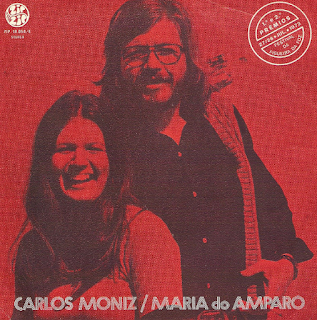

While touring with Afonso and others, Carlos Alberto Moniz also developed a repertoire of his own. With his girlfriend (and later first wife) Maria do Amparo, he formed a vocal duo specializing in Azorean folk repertoire.

“Maria is an Azorean like me, but I met her in Lisbon and that's where we became a couple. She was passionate about Azorean music and collected traditional island melodies, to which we added a touch of our own. Azorean melodies had been a love of mine already before meeting her. Most of them are incredibly melodious! In 1969, I first performed on nationwide television with ‘Samacaio’, an Azorean traditional. Shortly thereafter, I met Maria, discovering we had a shared passion. Over the next 15 years, we released several albums. Our recording of the song ‘O ladrão’ even did well in the charts! It was an Azorean traditional, a fun song telling the story of a thief stealing things here and there. This was still under the ancient regime of Caetano. One day, right after a radio broadcast of one of Caetano’s speeches, the technician, instead of putting on Vivaldi, played our song, ‘O ladrão’ - ‘O Thief’! Afterwards, the guy was heavily reprimanded by his superiors. He has always maintained it was a mistake, but I'm not so sure – in fact, I think he must have done it on purpose!”

In 1973, Maria do Amparo and Carlos Alberto Moniz won the Figueira da Foz Song Festival with a song written and arranged by Carlos Alberto himself, “In fact, that was kind of funny, because the second place was for a song composed by Pedro Osório. Pedro was a good friend from the Lisbon music scene and someone who usually wrote the arrangements for us. One day, while sharing with him my ideas I had for a new record by Maria and myself, Pedro said, “No, I am not going to write the arrangements for you – this time, you should do them by yourself!” I was astonished, because I lacked the knowledge to do that and I implored him… I mean, he was a friend!"

"What he wanted to bring about, in fact, was to force me to improve my knowledge of music theory. He felt I could be an arranger myself – and he was right. Technically, I was actually quite a bad guitarist… not nearly good enough to be of much use in studio sessions, but I always had ideas about the instrumentation. I followed arranging courses at Lisbon’s music academy for four years, but perhaps more important than that was the advice of Pedro Osório and another influential studio arranger, Thilo Krasmann. Thilo gave me some theory books, ‘Sounds and Scores’ by Henri Mancini for example… and he took time to sit down at the piano with me, listening to my ideas and giving his opinion. Thilo could always be trusted to be honest. When he didn't like a song or an arrangement, he would tell you so – bluntly, in the face, something which a native Portuguese wouldn't do so easily. He was a great guy and a fantastic musician. For my learning curve as an arranger, his contribution was crucial. So when I received the winner’s medal in Figueira da Foz in 1973, Pedro, perhaps a little frustrated about coming second, joked about how he should never have given me the idea to study arranging, “What have I done… you learnt too much!”

Apart from all activities mentioned in the above, during the 1970s Carlos Alberto Moniz worked on studio sessions, not only as a fledgling arranger, but as a guitarist and backing vocalist as well. In this role, he worked with the likes of José Carlos Ary dos Santos, Paulo de Carvalho, Tony de Matos, Fernando Tordo, and many others. Moreover, he was part of several short-lived groups, such as Improviso, Outubro, and Os Jagunços do Ritmo – all of them including Maria do Amparo, who became his wife in 1973. Besides, with Pedro Osório and Samuel Quedas, he formed the gimmick trio SARL in 1974.

Record release of the Figueira da Foz winning song: Maria do Amparo and Carlos Alberto Moniz

“SARL and Os Jagunços were essentially joke groups… hanging out with music friends and having a good time together. Outubro was something else. Apart from Maria and me, it included Alfredo Vieira de Sousa, Pedro Osório, and Madalena Leal. We toured quite extensively and recorded two albums, neither of which were million sellers, but they contained some really good melodies which are dear to me.”

In the latter half of the 1970s, Carlos Alberto Moniz became involved in writing music for television as well. José Barata-Moura, a professor of philosophy but a gifted writer of children’s music at the same time, asked Moniz to be the guitar player for a studio session of recordings for the children’s programme O fungagá da Bicharada (1976).

“That was because Barata was an even worse guitar player than me,” Moniz laughs. “So that is the reason he asked me for his sessions and we quickly became friends. Before Barata, all children’s music had simply been adult songs with diminutives in the lyrics. Instead, he chose to write lyrics about animals, the clock, the colours… and thereby opened a new way of approaching children’s music. At one point, he asked me to write 12 additional songs for his programme – which I did; additionally, with Maria, I released an album of these songs… and we continued being involved in writing and singing music for children in the following years.”

Over the 1980s, Moniz was involved as a composer and musical director in many different children’s programmes, among which Zarabadim and Uma história ao fim do dia, which involved writing a new bedtime song for children each day – for this daunting task, Moniz mostly worked with lyricist José Jorge Letria. Moreover, he got a foot in the door in other television work as well. In 1981, co-composing with Thilo Krasmann, he wrote and arranged the music to variety show Sába dá bádu; he also penned the scores to several television films and series, including Era uma vez (1987) and comedy detective series Duarte e companhia (1988-89).

Grupo Outubro, from left to right: Carlos Alberto Moniz, Madalena Leal, Pedro Osório, Maria do Amparo, and Alfredo Vieira de Sousa

“That series was great to work on. Rogério Ceitil, the author, director, and producer, was a great professional, but quite a demanding guy at the same time. He showed me the film on an old-fashioned moviola in a small studio and I played the accompanying music simultaneously on a piano – and we recorded it directly on tape. Sometimes, Rogério’s shepherd dogs would bump into the room and run over the moviola, after which we had to put the bits and pieces of celluloid back again. If anything, this was improvisation!"

"As a composer of TV music, you have to be able to work fast. I try to be a perfectionist, but when there is a deadline, the job has to be finished. The real perfectionist will never work for television. At the same time, it can be a frustrating job. I wrote some jingles and intro music to programmes as well. When I played the tape to the director or producer, they would switch on a chronometer – and their reaction would be, “Fantastic, 9 seconds!”, or, “No, no, this is no good – 11 seconds, too long!” They didn't care at all about the melody itself. Television sometimes means you have to stop being a creative artist; it's mostly about delivering what others want from you.”

All the while, Carlos Alberto Moniz continued working as a studio arranger with the likes of Luisa Basto, Fernando Tordo, and Zélia Rodrigues, while – after separating from Maria do Amparo – cautiously embarking on a solo career as a singer as well. In 1987 and 1989, he released two entirely self-composed, self-arranged, and self-produced albums, ‘Histórias de um Português qualquer’ and ‘Rua dos navegantes’. For the last-mentioned LP, with lyrics by José Jorge Letria, he received the Prémio Casa a Imprensa, an annual prize awarded by music critics. As a soloist, he participated in international song festivals in Rostock and on Corfu.

When asked if it was not until breaking up with Maria do Amparo that he managed to find his own voice, Moniz comments, “There may be some truth in that. I have enjoyed immensely singing my own material, but, though it was not my plan from the outset, I feel, in retrospect, that every singer and every musician should work in groups before going solo. By listening and adapting to others, you learn a whole lot, not only in terms of vocals, but rhythmically as well. Singing in groups, first in the Azores and later with Maria, was an important learning experience for me.”

With José Jorge Letria and French singer-songwriter Georges Moustaki at the 1991 Corfu Song Festival, Greece

Whereas Carlos Alberto Moniz had worked as a television composer exclusively for state broadcaster RTP, in 1993 he switched to the new private station TVI, becoming its Head of Children’s Programmes. At TVI, he hosted a daily children’s show, A casa do Tio Carlos (= At Uncle Charles’ House).

“My switch to TVI came as a shock to RTP. I had been working for several years on a weekly children’s show called Arca de Noé, for which, each time, a different animal was at the centre of attention. With José Jorge Letria, I wrote a suitable song for each of these programmes, in total perhaps some 140 songs. That programme was quite successful, which is why TVI was interested to sign me. In A casa do Tio Carlos, I was Uncle Charles and it was a success; I received guests from the world of entertainment… Dulce Pontes, for example, and many others. I recall a special outdoor show at the Feira Popular in Lisbon, which was organized as a spin-off of the TV programme – and a couple of thousands of children attended. That must have been the peak of my popularity! After less than a year and a half, RTP persuaded me to come back to re-start Arca de Noé, which I did; perhaps I shouldn't have done that, because their main reason for getting me back was probably that their audience shares had dropped due to A casa do Tio Carlos; but then, those are not my worries, because I have enjoyed working for RTP as well as TVI.”

In the 1990s and 2000s, Carlos Alberto Moniz continued composing music for television programmes, amongst which the miniseries O beijo de Judas (1992) and films such as Arre potter qu’é demais (2007) and Vozes de abril (2008). Although, due to the studio revolution which saw synthesisers and computers replacing orchestras in pop music, arranging work more or less dried up, Moniz orchestrated the album ‘As canções possíveis’ with poems of Nobel Prize winner José Saramago sung by Manuel Freire (1999) and Paulo de Carvalho’s 2003 release ‘Até me dava jeito’, for which he co-signed for the arrangements with Mike Sergeant. Furthermore, he co-composed and arranged the music to about a dozen of revues, which were performed at the Maria Vitória Theatre in Parque Meyer, right in the heart of Lisbon.

“Revue is a form of theatre which is more or less extinct nowadays, but until about 2005, it still drew good crowds. I started as the assistant to Thilo Krasmann, who was the director of revues at the Maria Vitória Theatre. Everytime Thilo recorded the music to a performance, I joined him in the studio and helped him out with additional material. When he stopped working for the theatre, I took over. We always worked exclusively with backing tracks; there was no live orchestra playing. Working on revues involved writing and rehearsing songs at very short notice, adapting arrangements until the evening before the premiere.”

True to his heritage: Carlos Alberto Moniz following the band at Terceira’s annual street festival. Moniz, commenting, “To my children, I've always explained that it is as important to lead the Eurovision orchestra as it is to play drum at the last row of your local band”

In 1999, Moniz released not one, but two solo albums, ‘Marchas e passodobles’ and ‘Clássicos Açorianos’, proving his continued attachment to his home islands and its folk music. “True, I'm a proud Azorean. Not a chauvinist, but still; proud. Every year, there is a big open air music festival on Terceira Island. Music bands march through the streets performing marches and two-steps. For each edition since 1975, I have composed an original piece to be played at the festival. The ‘Marchas e passodobles’ album was a compilation of these compositions. ‘Clássicos Açorianos’ was a more daring project. I imagined what it would be like to have the beautiful folk melodies of the Azores played by string quartet. I found a fantastic pianist-arranger to write arrangements in classical style to 16 traditional songs – no modern influences, just classical by the book… and it turned out very well.”

Being the easy-going and talkative person that he is, Carlos Alberto Moniz was asked to be the host of a weekly radio talk show for Antena 1, called Perto do coração, which ran for 6 seasons (1998-2004). In it, he interviewed artists and politicians for a two-hour-conversation. It was the start of a career as a presenter for several more radio and television programmes, including ‘Casa dos Açores’ (2004-06), a TV talk show going on air live for RTP Açores and RTP Internacional. Between 2008 and 2015, he hosted Portugal sem fronteiras, another live entertainment show, this time for RTP1.

When asked if he likes the medium of television, Moniz responds, “As long as it is live, yes! Pre-recorded television is a mess. Directors continue to ask you to repeat your song or conversation, because of some trivial thing – there was a fly in the image, for example. In the process, all spontaneity is killed. For a live show, you know in advance you have one hour or two hours, and whatever happens, is transmitted. As a musician, I've always preferred improvising as well. It gives me a good feeling to simply put trust in the team of people working on a performance or a programme, and it usually results in a certain amount of naturality which comes across well with the audience.”

As a recording artist and solo singer, Carlos Alberto Moniz has continued working until today. In 2003, he recorded an album with poems about the Azores, to which he composed new music, ‘Herdeiros da Maresia’; among other releases, he made a new CD in 2014, ‘Vinho dos poetas’, for which he composed a song to each wine region of Portugal. With his considerable repertoire, he has performed across Portugal, ranging from big podia, such as the Estoril Casino, to the very small.

At work in the recording studio: Carlos Alberto Moniz with Pedro Osório, shortly before the latter’s passing in 2011

“The inspiration is still there, both as a songwriter and as a performer. It doesn't really matter if there is a theatre of 1,000 spectators or two dozen people in a retirement home, to whom I share my recipes for cakes in between songs. I do 80 percent of my performances for free… it simply is a passion, something I hope to continue doing for as long as possible.”

Having worked as guitarist, singer, composer, arranger, radio and television host, would Carlos Alberto Moniz – looking back – not rather have specialized in any of these activities instead of being the ‘Jack of All Trades’ that he is?

“No, I'm an enemy of specializing. For example, at a given point, I received lots of commissions to compose film music… and I thought to myself how nice it would be to go to America to study film composition and learn more – but it would have meant I had to leave behind performing my own songs on all these different wonderful stages in Portugal. Throughout my career, I have always mixed up learning with working, and recording with performing… and I guess, now that I will be 70 this year (the interview took place in January 2018 – BT), it is better to continue just doing that. Combining all these different things at the same time is what I did in the 1970s and what I am still doing now. My life is pretty much the same as it was 40 years ago… well, hopefully I make less mistakes now!”

From 1983 onwards, with some breaks in between, Carlos Alberto Moniz has served the SPA, Portugal’s Association of Composers, Authors, and Music Publishers as a board member. In 2000, he received the Medal of Honour of his birthplace Angra do Heroísmo and, three years later, Portuguese president Jorge Sampaio made him Commander in the Order of Merit of his country. Moniz has four children and three granddaughters. His daughter Lúcia is a singer and movie actress, who, most notably, performed in the UK romantic comedy Love Actually, a box-office success in 2003.

On the island of Madeira for a one-off performance of songs by Max (Maximiano de Sousa) with a full symphony orchestra, January 2018

EUROVISION SONG CONTEST

Although it was in 1990 that Carlos Alberto Moniz made the first of his two appearances as the conductor of the Portuguese entry in the international Eurovision final, his involvement in the contest goes back much further than that. In 1973, with Ana Teodósio, Manuel José Soares, and Carlos Alberto’s wife Maria do Amparo, he was part of the quartet Improviso which participated in the Festival RTP da Canção, Portugal’s annual selection programme for the Eurovision Song Contest.

“We were a group brought together shortly before the Festival RTP and Improviso was the only name we could come up with – because we were an improvised group! The attraction of taking part was first and foremost the Festival RTP itself. Back in the Estado Novo days, it was practically the only window in Portugal to show that we existed at all. If we won the Eurovision ticket, that would have been fine – but merely as a bonus. Our song ‘Cantiga’ was written by João Rafael and well-constructed, but with no chance of winning. I remember Fernando Tordo was the winner (with the song ‘Tourada’ – BT). At the time, I was very happy for him; later on, he became a great friend of mine.”

The 1979 edition of the Festival RTP da Canção was a particularly busy one for Carlos Alberto Moniz, as he participated with 3 different songs, two of which were self-penned and performed in a duet with Maria do Amparo, ‘A outra banda’ and ‘Camponês dos campos de água’; both were eliminated in the semis. Still, Moniz ended up performing in the final with ‘Uma canção comercial’, a song composed and arranged by Pedro Osório and performed by SARL – Sociedade Artística e Recreativa Lusitana, a trio comprising Osório himself, Moniz, and Samuel Quedas. In spite of the fact that the song was an evident parody of what a Eurovision song should be, SARL came quite close to winning the ticket to the Eurovision final in Jerusalem, finishing third behind eventual winner Manuela Bravo.

“SARL was a joke project,” Carlos Alberto explains. “The abbreviation is used in Portugal for joint-stock companies, but Pedro gave it a different meaning. It was his idea from the outset, and he composed all material. In the 8 years of our existence, we didn't tour – this was really only about singing funny songs and getting some televised attention. ‘Uma canção comercial’ was our highlight with SARL. In the 1970s, as ABBA won Eurovision and the contest was taking a different direction, we tried to follow these developments. The lyrics are, "I have to do a commercial song which fills all the parameters of Eurovision," describing the recipe for a winning song… and it almost won, as we came third! When we saw so many people enjoyed the song, we feared it would develop into something bigger… I mean, who would want to win international fame for wearing your grandmother’s hat and a robe worn over your pyjama, which is what I did?"

Single release of the two songs with which Carlos Alberto Moniz and Maria do Amparo took part in the 1979 Festival da Canção

"Maybe, deep down, Pedro was really serious about SARL. To my mind, he always was better as an arranger than as a composer. He wrote dozens of brilliant arrangements for Paulo de Carvalho, Fernando Tordo, and others, but only a couple of really good songs. ‘Uma canção comercial’ isn't among them. The chords were correct, the words were funny, and our vocals were OK, but the flame to turn it into something really good was lacking – which is probably something that could be said about the SARL project as a whole.”

With SARL, Carlos Alberto Moniz took part in two more editions of the Festival RTP, in 1980 and 1982, while also participating in the year in between, this time once again as a duo with Maria do Amparo with a Earth, Wind & Fire style song written by the duo itself: ‘Olá rapariga, olá’. In 1986, Moniz had a go at the Portuguese pre-selection, performing ‘Canção para José da Lata’ with a backing band comprising, among others, Armindo Neves.

“That year, the Azores were allowed to submit three songs for the Festival RTP,” Moniz recalls, “and mine was one. I really love that song, with very good lyrics by Álamo de Oliveira about a folk singer from the islands. The music and the arrangements are a combined effort of myself and the rest of the group. We were not a regular band… these were simply the guys with whom I had recorded the song in the studio. Nevertheless, it worked really well on stage, but of course the song itself was too complicated to do well in Eurovision. On the Azores, it's a song which is still regularly played on the radio even nowadays.”

At the Festival RTP da Canção, over the years, the practice of who conducted the orchestra changed from year to year. Sometimes, the task of conducting all entries, regardless of who had written the arrangements, was given to one maestro – the last edition with this ‘system’ was in 1980 with Jorge Machado as the musical director and the conductor who accompanied the winning act to the international Eurovision final. After that, apart from the editions without a live orchestra (such as in 1984 and 1986), there was the habit of allowing each act to pick the conductor of its choice; in most cases simply the musician who had written the orchestration. As such, Carlos Alberto Moniz made his first appearance as a conductor in the Festival RTP da Canção in 1987, though, between 1980 and 1986, he had already penned the orchestrations to six songs taking part in the competition, performed by the likes of Helena Isabel, Fernando Tordo, and Zélia Rodrigues, which were either conducted by other maestros or performed with a backing track instead of a live orchestra.

Moniz with the band which backed him up at the 1986 Festival RTP da Canção, from left to right: Armindo Neves (guitar), José Marinho (synthesizer), Manuel Necas Félix (drums), Carlos Alberto Moniz himself, António Ferro (bass), and João Nuno Represas (percussion)

In the 1987 Festival da Canção, held on the island of Madeira, Carlos Alberto Moniz conducted the orchestra for his own arrangement to ‘Imaginem só’, a song composed by Maria Guinot and performed by Ana Alves. How much of a conductor was Moniz by 1987?

“Well, admittedly, I'm not a good conductor, in spite of being quite a good arranger. I never studied any classical orchestra conducting. Instead, I picked up my knowledge by watching how other maestros worked in the studios, guys as Pedro Osório and Thilo Krasmann… but they never conducted much better than I did. Thilo wrote perfect arrangements, but his way of conducting was slightly unorthodox – so, technically speaking, I maybe didn't have the best role models! My way has always been to keep it simple and stay away from the dramatic movements which belong to classical conducting… and, whether it was in the studio or at a festival, the orchestra musicians were my friends and forgave me my lack of technique! As a conductor of my arrangements in studio recordings, I had picked up enough experience to stand up in front of an orchestra on stage. I remember the festival in Madeira with Ana Alves, but not because of the music. All participants of the programme stayed on the island for 10 days, enjoying the wonderful sunny weather. I only had to work on a couple of rehearsals and then do the television show in the end. It was very easy.”

In fact, Ana Alves came quite close to winning the right to represent Portugal at the Eurovision Song Contest in Brussels, but in the end she finished third, as the group Nevada and their song ‘Neste barco à vela’ walked away as winners. In 1989, Carlos Alberto Moniz returned to the Festival RTP da Canção as the arranger and conductor of a song performed by José Alberto Reis, ‘Palavras cruzadas’. Its composer, Carlos Paião, had died in a car accident several months prior to the festival. On the night, the song finished 4th. Nevertheless, Moniz walked away with a trophy at the end of the night – the prize for the best orchestration, though he had to share it with Armindo Neves for his arrangement to one of the other entries.

In 1990, Carlos Alberto Moniz was approached by Luís Filipe Aguiar (1952-2015) to be the musical director for his entry in the Festival RTP da Canção, a song called ‘Há sempre alguém’, performed by Nucha, a twenty-three year old singer from Águeda. Luís Filipe wrote the music to this happy, upbeat song in collaboration with Jan van Dijck.

A moment of relaxation in rehearsals in the 1989 Festival da Canção in Evora - the five arrangers being 'conducted' by the orchestra's drummer; from left to right - Ramón Galarza, Carlos Alberto Moniz, Fernando Correia Martins, Armindo Neves, and Luíz Duarte

“Luís was a producer and studio director,” Moniz explains. “He asked me because, at that time, I recorded my compositions to the Arca de Noé television series in his studios. He liked my professional approach and we were friends. Luís already had a basis for the arrangement, but he didn't have the technical ability to write for classical instruments. He gave me a midi file with ideas for the orchestration which he had created on his keyboard. I remember it was an extremely complicated arrangement, with several tracks on top of each other and lots of double notes. My job was to make it simpler… to choose between all these different suggestions which he had put into the file while adding some ideas of my own without killing his original intentions for the song. So to put it entirely correctly, the arrangement was mostly by Luís, while I was the song’s orchestrator. I went to the Festival RTP without any expectations, but young Nucha turned out to be a very good performer for this type of commercial music. The combination of song and singer worked well and that's why she won.”

The logical result of this was that Carlos Alberto Moniz would also be the conductor of the Portuguese Eurovision delegation at the 1990 international festival final, held in Zagreb in what was then still Yugoslavia, a country which – in retrospect – was on the brink of civil war. Was there something of that in the air in 1990?

“Zagreb was beautiful and we enjoyed being there," Moniz comments, "but we felt something which was not good. On every trip which was organised for us, we were accompanied by double or triple security… there were armed forces behind us and police officers on all street corners. This was obviously not a trouble-free country, but we could never have predicted what happened there one year later…”

Compared to the Portuguese national final, the sound of ‘Há sempre alguém’ had been slightly modified. Instead of an entirely live version played by the orchestra, the Zagreb version included a backing track of keyboard and drums.

“Luís Filipe had insisted that we should make a playback track to which the orchestra would play along to give the song a sound which was somewhat steadier. It was his production, so it was up to him to decide, but I felt slightly embarrassed about the situation. I didn't feel the courage to start the rehearsal with the Yugoslav orchestra by saying to the pianist and the drummer, “You and you do not play – you can leave”; that would have been professional, but my heart would not let me. So I said to them instead, “I am sorry about this, but we have parts of this pre-recorded and put on a tape.” The arrangement itself was not difficult for the string and brass sections. When writing arrangements for pop music, I often thought about what Thilo Krasmann had taught me, “Give them a score which is easy to play.” It was a wise lesson, because musicians will like it when you give them a relaxed time while rehearsing. There was nothing to worry about with the Zagreb orchestra; they played well.”

Nucha with her winner's trophy of the 1990 Festival RTP da Canção featuring on a cassette with all entries in the competition

During rehearsals, Moniz could not help noticing that hardly any camera attention was given to the orchestra, and none at all to the maestros conducting it. As it turned out, in order to win some time, the production team had decided to do away with the traditional bow allowed to each country’s conductor in advance of the song.

“Slowly, it started to dawn on me that on television, this would just be about singers and backing choirs, backing choirs and singers... and I was not happy. In between rehearsals, I had a chat with the Greek maestro (Mike Rozakis – BT) and the two of us agreed that we should not let this happen. We decided to draft a short letter to the organisation committee specifying that we strongly disagreed with their decision; and we stated that, if in the general rehearsal we would not be shown on screen, we refused to perform at all… and, without us, the orchestra would not play – so there would not have been a festival!”

“Once we had put together our little document, I went to the hotels of all delegations, looking for all conductors. I had to hurry, because, as far as I remember, this was on Saturday morning – in other words, on the day of the festival. I took much time, but I found all my colleagues and they all signed up. The Greek maestro and I… we took it to TV Zagreb’s head office, where we were courteously received. They explained to us that it was a matter of keeping the programme’s total duration in check, but we replied that this was nonsense. They could at least show us while counting in the orchestra… we would have to do that anyway – instead of filming the lamps in the ceiling of the hall, they could film us! They said they would discuss the matter – and the Greek guy and I decided to stay to wait for the decision. It was hot and we stood there, the whole afternoon, outside a TV director’s office… but in the end they gave in! I wish I still had that piece of paper with all those signatures, because it is a precious document. I felt it was important to stand up against all of this, because I suspected this was the beginning of doing away with the orchestra altogether and replace it by playback – which indeed happened some years later.”

And thus, TV viewers from all over Europe saw Carlos Alberto Moniz counting in the orchestra for the Portuguese entry, with a big smile on his face and… wearing a striking black jacket with big white numeral signs on it. He also wore it for the Portuguese pre-selection back in Lisbon. Was there any special reason for choosing this jacket? Moniz cannot help but laughing when reminded of his costume.

“I bought it in Stockholm! I was in Sweden to do a performance of poetry at the Stockholm University. José Saramago, who hadn't won the Nobel Prize yet (Saramago won the prize in 1998 – BT), held a presentation of his poems and I performed some Portuguese poetry put to music while playing the guitar. One or two days before the concert, I did some sightseeing in Stockholm and found myself in a clothing shop, where this jacket caught my eye. The shop assistant claimed they had only made two of that type of clothes – and that the first one had been sold the day before to Mick Jagger! Following my first impulse, I bought the jacket. No idea if the Jagger story was true or a selling trick! Back then, I had some 15 kilos less than nowadays and the jacket suited me well, so I wore it at the Eurovision Song Contest. Even nowadays, friends occasionally remind me of that suit. I never threw it away, but gave it to my daughter Lúcia some time ago… so she's wearing it now!”

Stage photo taken during the rehearsals of Portugal’s entry at the 1990 Eurovision Song Contest: Lisinski Hall, Zagreb

Asked if he remembers some of the other participants of the festival in Zagreb, Moniz instantly replies, “Toto Cutugno (the singer from Italy who eventually won the contest – BT)! During rehearsals, he was constantly making jokes at me because of football. He said he was a Milan supporter and asked what my favourite club was. Well, Benfica, I answered… and he kept on posing me the same question the following days, and although I realised he was fooling around, I did not understand until someone explained to me that fica is a really bad swear word in Italian. Every time I said 'Benfica', he was in stitches – if anything, it illustrates how relaxed the atmosphere amongst the artists was. I also remember the conductor from Ireland (Noel Kelehan – BT). He played the piano very well and he also played a lot of Scotch! The amount of alcohol this guy could tolerate was incredible! When I asked him to sign our petition of all conductors, he said, “Alright, I will sign the paper, but I don't agree very much with what is going to happen… because of you, I run the risk of my head appearing on television – and my wife thinks I am in New York!” Unforgettable, this old chap with his white hair – what a character!”

On the big night of the contest, Carlos Alberto Moniz could have been forgiven for feeling nervous about conducting the orchestra after what had happened to the Spanish entry. Due to a technical blunder, Spain’s MD Eduardo Leiva could not hear the click track of the backing tape and as a result the performance of the entry from Spain had to be re-started.

“Maestro Leiva was angry,” Moniz remembers, “and he had every right to be angry. Backstage, we were all talking about it. Did the technicians do it on purpose because of how the conductors had stood up against the organisation? We will never know. I was kind of nervous; I felt the responsibility and the meaning of power – while walking on stage, the thought crept into my head that I could stop the entire show by not counting in the orchestra. Of course, it was an idiotic thought and I had no reason to not simply do my job – I suppose it is a normal thing when realizing that, in a couple of seconds, millions of people will be watching you.”

In spite of Nucha’s confident performance, ‘Há sempre alguém’ only picked up 9 points – with only Norway and Finland scoring worse. “The score is never important to me,” Moniz comments. “The performance sounded well and we had nothing to be ashamed of. Until Salvador Sobral won the contest for Portugal (in 2017 – BT), we believed it was impossible to win the contest. I mean, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark always seemed to exchange votes, and there were some other groups of countries sticking together as well. As far as I remember, the entire Portuguese delegation accepted the result as a fact of life. Our delegation was led by professional and helpful RTP people; they even sent me a note supporting my decision to send a protest to the organising committee about the conductors and the orchestra.”

Dina and her backing group during rehearsals at the 1992 Eurovision Song Contest in Malmö

Two years later, in 1992, Carlos Alberto Moniz was again part of the winning team of the Festival RTP da Canção; ‘Amor d’água fresca’, a quite original love song composed and performed by Ondina Veloso – in arte: Dina – with lyrics by actress and poet Rosa Lobato de Faria. One additional attraction of the song was the wonderful string arrangement. Again, Moniz was commissioned to do the orchestration for the song thanks to Luís Filipe, its producer and also arranger of the record version.

“Luís simply trusted me to respect his ideas and translate them into notes. I approached this song the same way as ‘Há sempre alguém’ in 1990. Some strings, some interesting rhythmical lines – the starting point is knowing about harmony, and the rest flows from that. I thought it was a good song; the lyrics and music worked well together. Rosa Lobato de Faria was an able lyricist. Moreover, the melody was different from the standard pop song; most songs in the charts and in Eurovision sound similar in terms of rhythm and melody, but, in a way, this one stood out.”

The 1992 Eurovision Song Contest was organised in the southern Swedish town of Malmö. "That was lovely, because I like Sweden a lot. The security measures were less tight than in Zagreb; in fact, as far as I recall, there were none at all. We had the opportunity to travel across the sea strait to Copenhagen in Denmark for a day trip. On the other side, we bumped into Mário Soares, the Portuguese president who happened to be on a state visit in Denmark… and we said, “Hi, Mr President!” When he heard we were Portugal’s representatives at the Eurovision Song Contest, he invited us to have dinner with him that night. We explained to him that our delegation consisted of some 30 people, but he said it was no problem. “Simply come, all of you!”, he said. That evening, at the Copenhagen town hall, we understood why he was not worried about the expenses, because it turned out the dinner was offered by mayor of Copenhagen! We accompanied our president to the dinner, had a great time, and were sailed back to Malmö that same night.”

As so often in the history of the contest, Portugal had to make do with a meagre score. Dina and ‘Amor d’água fresca’ finished 17th in the contest. “I don't know if Dina was disappointed. All I know is that the rehearsals with the orchestra were flawless and that Dina was a nice artist to work with. On the other hand, I don't know much about the policy of winning and losing. I loved going to Eurovision because I was looking forward to conducting an orchestra abroad and to listening to the work of composers from other corners of Europe. To me, that was the importance of Eurovision – gathering people of different cultures.”

Father and daughter at the 1996 Eurovision Song Contest: Carlos Alberto with Lúcia Moniz in Oslo

After one more isolated arrangement for the Festival RTP da Canção in 1993 to a song which was eliminated in the semi-final (‘Baila, baila’ by Tozé Lobo), Carlos Alberto Moniz returned to the Portuguese Eurovision pre-selection as its musical director in 1996; in this capacity, he conducted the three participating entries of which the arranger declined leading the orchestra himself; ‘Start stop’ by Vânia Maroti, ‘Canto em Português’ by Patrícia Antunes, and ‘Ai a noite’ by Elaisa. The programme, broadcast from the Teatro Politeama in Lisbon, was a special one for Moniz, as his own daughter Lúcia participated as a vocalist – and she won, with the song ‘O meu coração não tem cor’, a delightful folk melody written by José Fanha and Carlos Alberto’s old friend Pedro Osório.

“Of course, I was extremely proud of my daughter, but I couldn't jump onto the stage to embrace her, because I was the MD of the show and had to remain neutral while the programme was running! Afterwards, I was criticised by some people for not showing how happy I was, while someone else cynically remarked that Lúcia had only won because I was the leader of the orchestra!"

"When Pedro Osório won, he told RTP officials he needed an assistant conductor to accompany him to the Eurovision Song Contest in Oslo; he said it was to check if the sound was right while he was conducting the orchestra, but of course it was just a pretext to allow me to come along! It was great being in Norway with Lúcia; and all members of the backing group as well as José Fanha, and Pedro Osório – who were good friends – so we were a group of happy people in Oslo. For press conferences, it was not just Lúcia; we all came along, and the background group took along their musical instruments. We were kind of popular with the journalists. Unfortunately, RTP did zero for the promotion of the song. The record release was a clumsy demo version and it was accompanied by an A4 sheet of paper with some biographical information about Lúcia… that was it. When she did very well at the beginning of the voting, the director of RTP who was with us in the greenroom, was despairing. “Oh, what a tragedy, what is going to happen if we win!?”, she screamed.”

In the end, Lúcia Moniz and ‘O meu coração não tem cor’ finished 6th, the best Portuguese result ever in the contest – that is, until Salvador Sobral finally, after over fifty years of Portuguese involvement in the contest, broke the spell and gave the western half of the Iberian peninsula its first Eurovision victory in 2017. Given his fatalism about Portugal’s result in the festival over the years, Carlos Alberto Moniz must have been surprised when ‘Amar pelos dois’ won the contest.

“Well, I was a member of the professional jury in Portugal which chose him in the pre-selection, awarding the maximum of points because the composition and the string arrangement were so beautiful. The general public in Portugal had another favourite, but fortunately our votes tilted it in Salvador’s favour. Regrettably, a song like ‘Amar pelos dois’ has become the exception in Eurovision. I've stopped watching years ago. It is a nice show for people who like that kind of entertainment, but, to me, it has become a format. Not even Salvador can change the recipe of Eurovision, I'm afraid. It has gone too far adrift to be saved. I must say, though, I won't forget the day he won. I happened to be in Tokyo. That very same day, Pope Francis visited Portugal and Benfica won the Portuguese league title – so everything came together… in one word: fantastic!”

21 years later - Carlos Alberto and Lúcia Moniz in 2017

OTHER ARTISTS ABOUT CARLOS ALBERTO MONIZ

So far, we have not gathered comments of other artists about Carlos Alberto Moniz.

EUROVISION INVOLVEMENT YEAR BY YEAR

Country – Portugal

Song title – “Há sempre alguém (Sempre)”

Rendition – Nucha (Christina Baldaia)

Lyrics – Francisco Teotonio Pereira / Frederico Teotonio Pereira

Composition – Jan van Dijck / Luís Filipe

Studio arrangement – Luís Filipe

Live orchestration – Carlos Alberto Moniz

Conductor – Carlos Alberto Moniz

Score – 20th place (9 votes)

Country – Portugal

Song title – “Amor d’água fresca”

Rendition – Dina (Ondina Veloso)

Lyrics – Rosa Lobato de Faria

Composition – Ondina Veloso

Studio arrangement – Luís Filipe / Ondina Veloso

Live orchestration – Carlos Alberto Moniz

Conductor – Carlos Alberto Moniz

Score – 17th place (26 votes)

SOURCES & LINKS

- Bas Tukker interviewed Carlos Alberto Moniz on January 10th, 2018

- Photos courtesy of Carlos Alberto Moniz & Ferry van der Zant

WEBSITE

No comments:

Post a Comment