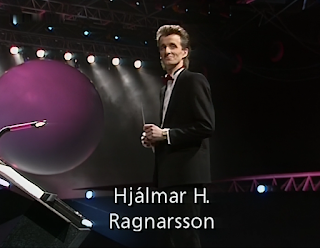

The following article is an overview of the career of Icelandic pianist, composer, and conductor Hjálmar Ragnarsson. The main source of information is an interview with Mr Ragnarsson, conducted by Bas Tukker in Kópavogur, Iceland, July 2012. The article below is subdivided into two main parts; a general career overview (part 3) and a part dedicated to Hjálmar Ragnarsson's Eurovision involvement (part 4).

All material below: © Bas Tukker / 2012

Contents

- Passport

- Short Eurovision record

- Biography

- Eurovision Song Contest

- Other artists about Hjálmar Ragnarsson

- Eurovision involvement year by year

- Sources & links

PASSPORT

Born: September 23rd, 1952, Ísafjörður (Iceland)

Nationality: Icelandic

SHORT EUROVISION RECORD

Hjálmar H. Ragnarsson was the conductor of the Icelandic entry to the 1987 Eurovision Song Contest in Brussels, ‘Hægt og hljótt’. Interpreted by Halla Margrét, this haunting ballad, composed by Valgeir Guðjónsson and arranged by Jon Kjell Seljeseth and Ragnarsson himself, finished 16th.

BIOGRAPHY

Hjálmar Helgi Ragnarsson was born in Ísafjörður in the remote West Fjords region in north-western Iceland, where his father had been running a music school since 1948. “Up until 1948, my dad had had a colourful life," Ragnarsson explains. "Hailing from the northeast of Iceland, he had moved to Canada in 1920. He had a passion for music, but his poor background did not allow him to go to a European conservatory. In America, he studied privately, meanwhile earning a living as a piano accompanist in North Dakota and the bordering regions of Canada, where quite many emigrated Icelanders lived."

"In 1942, when the Americans took over from the British troops on Iceland, he was stationed in Reykjavík as an interpreter and member of USA’s counterintelligence. There, he met my mother. Upon war’s end, he left for the US again, only to return three years later when he was commissioned by authorities in Ísafjörður to found a music school. For as long as I can remember, I was surrounded by music… there was always so much teaching going on in our house, that I usually had to go practicing somewhere else. Apart from studying the piano, I was taught the basics of music theory, arranging, and accompanying. Though you might think otherwise in such an isolated location, Ísafjörður was an inspirational place to grow up: it is a town with a strong cultural heritage.”

In 1969, 16-year-old Hjálmar moved to Reykjavík to finish his secondary education at the Reykjavík Junior College, where he took his final examination three years later. Meanwhile, he managed to obtain the diploma of the eighth grade in piano at the Reykjavík College of Music (1971). Upon his graduation from college in 1972, Ragnarsson was given the opportunity to study music in the United States.

“Of course, I could have chosen another subject to study – I was especially interested in science – but, at that point, I was offered a scholarship to study music at a university in Boston. In those days, Iceland was in many ways an underdeveloped country. There was no fully-fledged conservatory yet and to obtain a degree in music there was no option but to go abroad. When I was told about this scholarship, I thought it was too good an opportunity to miss. All of my expenses were paid for by a private fund attached to an opulent American businessman.”

As a student at Brandeis University, Boston (1974)

Between 1972 and 1974, Ragnarsson studied the piano as well as music theory, conducting, and composition at the renowned Jewish-American Brandeis University in Boston Mass., obtaining his Bachelor of Arts diploma. “Though I only spent two years at Brandeis, these years changed my life. First of all, I was lucky enough to study with a brilliant teacher of the old school, Seymour Shifrin. When I came to the US, I was convinced that composing was a craft too unapproachable and too holy to be touched. It was only for the Gods – the great classical composers! To my mind, it did not make sense to try to even come close to the quality of writing they had achieved. Shifrin, however, made me compose melodies for an entire year, which was an excellent training. He gave me the confidence to get started. The real eye-opener at Brandeis, though, was discovering the department’s electronic music studio. Laying my eyes on all of these synthesisers really gave me a positive nervous breakdown! All these patches, all these oscillators, those new sounds… that is when I became confident enough, thinking to myself, “I can do that – the Gods have never used these instruments!” I bought a detailed manual by Allen Strange, ‘Electronic Music’, which was the first serious study on this subject. For the next ten years, I took it with me wherever I went; it was my Bible!"

" From that moment on, my ambition was to make these new sounds work in serious music, in all kinds of different ways – by writing music for synthesiser, by transforming sounds taken from vinyl records, by performing all of this. It was the ideal combination of my interests in music and science. In Iceland, where technology was still very basic in the early 1970s, I would not have been able to get involved in this world of new music the way I could at Brandeis with its excellent studio. Moreover, coming from Reykjavík, Boston was almost a different planet. It was a world of progressive ideas, student strikes, radical music… I also was interested in King Crimson, Led Zeppelin, The Doors, and Janis Joplin. In spite of the fact that I immersed myself in this new world, I worked on my music studies night and day.”

In 1974, Ragnarsson returned to Iceland, for the time being settling down in his native Ísafjörður. “It was a conscious choice to temporarily put a stop to my studies. I decided it was time to get my practical upbringing. I worked as a teacher at the local music school and conducted choirs. I was only in my early twenties and I was younger than all singers in these choirs! It was an excellent training. Apart from this, I teamed up with my sister Sigríður Ragnarsdóttir, a pianist, and her husband Jónas, who is a composer. They had already settled down in Ísafjörður. We wanted to accomplish some of our mutual ambitions. Amongst other things, we started a chamber ensemble, with which we performed quite often. I also had my electronic music performed… my first compositions!”

In 1976, Ragnarsson was offered a new scholarship in the US, but he delayed it for one year to study at the Institute of Sonology at Utrecht University, Netherlands. “At that time, the institute in Utrecht boasted the best research centre for electronic music and computer programmed music in Europe. It was thrilling, because I felt part of a group of people who were at the front of developing electronic music. In my idealism, I was convinced that it was only a matter of months before the computer would replace all these obsolete classical instruments… pianos, clarinets; I could not care less about them at that time. My final project in computer programming in Utrecht was not even about making music – it was about getting sounds from the computer; and it took me three months to produce them! This year in Utrecht was important for more than one reason, as it also allowed me to discover Europe and its culture. I visited Paris several times. No, I never considered finishing my studies in Europe, as I did not like the old-fashioned approach of European music academies. In America, the music department is an integral part of a university; there is much more interchange going on between music and other fields of science there.”

Hjálmar with his sister, pianist Anna Áslaug Ragnarsdóttir, in the RÚV studios (1985). "We were recording my Five Preludes for Piano, which I had composed especially for Anna," Ragnarsson explains

Moving to the United States again, Ragnarsson settled down in upstate New York, studying at the prestigious Cornell University (1977-80), where he obtained his master’s degree with a thesis dedicated to life and works of Iceland’s most prolific classical composer, Jón Leifs (1899-1968).

“At first sight, Cornell might seem a strange choice given my focus and interests,” Hjálmar comments. “Cornell is among the universities in America with the best reputation, but there was no atmosphere of avant-garde there at all. There were no possibilities to work on electronic music, for example, but I decided to give that a rest for a while. To balance that, Cornell offered me scholarly surroundings and excellent traditional composition teachers. I mostly studied theoretical subjects, such as music analysis. It was here that I started my research on Jón Leifs. Jón Leifs lived in Germany for most of his life, but his compositions were very much influenced by Icelandic folk music. In Iceland, his nonconformism did not win him many friends, though. He was always bickering with others and, not being very good at communicating his ideas, he often failed to bring across his message. His music is most unusual. For example, he composed a piece called ‘Hekla’ containing parts for about twenty percussionists!"

"At Cornell, with the largest library of Icelandic books in the United States, I was really absorbed by this research on Jón Leifs… it was a pristine subject that had not been touched upon by any scholar yet. I could have turned my master’s thesis into a Ph.D. project, but that was not my ambition at the time. Even though the university was most supportive about the Jón Leifs project, I was keen to return to Iceland… it is the freedom, the nature, and the family-like way of living that you want to be part of. In the end, Icelanders are proud of their identity and I am no exception.”

Upon his return in Iceland (1980), realizing it would be impossible to specialize in electronic music alone, Hjálmar settled down in Reykjavík as a freelance musician, heavily involved in cultural life and working in many different fields. To begin with, he made a living as a conductor and a teacher, including teaching at the Reykjavík College of Music (1980-88) – where he founded the Department of Theory and Composition. Ragnarsson made his mark as a conductor of different choirs, including, most prominently, the Choir of the University of Iceland (1980-83).

Conducting a theatre orchestra, c. 1986

“I was very lucky to be invited to conduct the university choir, as it was composed of young and dynamic people – similar age as I was at the time,” Hjálmar comments. “I was given the opportunity to experiment extensively and we mostly performed new music – including my own compositions – using synthesisers and unusual light effects… The highlight certainly was a concert tour to the USSR in 1983. Being the choir of a university, we were invited to perform our music at many Soviet universities. We toured for two weeks, performing in cities such as Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev. The authorities there expected we would mostly perform folk songs and music in traditional settings, but what we gave them was essentially hardcore avant-garde; cluster-sounds, discordant harmonies, movement, light, synthesisers! The reaction of the audiences was fantastic, but the local organisation went nuts. Our printed program was confiscated, as it contained lyrics which could not be allowed. We were thrown into the coach right after each concert, preventing any contact between us and the students."

"Our last concert was in Tallinn, Estonia. After we had given our reprise, the audience rose to its feet and sang the Estonian national anthem! There was a rebellious atmosphere. In retrospect, what we did perhaps was quite risky, but it was an unforgettable experience. After returning to Reykjavík, I decided to stop working with the university choir. Having done this unusual tour, I felt we had done everything within our grasp. Moreover, by then, my wife had become deeply involved in politics, becoming a Member of Parliament on behalf of the newly established Women’s Alliance. This left me no other option but to give up some of my professional activities.”

An important source of income for Ragnarsson in the 1980s and 1990s was his theatre work, composing and orchestrating the music to dozens of theatrical performances, ranging from operas and serious plays to an Icelandic musical version of Charlie And The Chocolate Factory. For most of these productions, Ragnarsson was the musical director as well, conducting the pit orchestra. For Iceland’s National Theatre, Ragnarsson was the musical director for Icelandic productions of Brecht’s Schweik In The Second World War (1984), Garcia Lorca’s Yerma (1987), and Ibsen’s Peer Gynt (1991), composing new music to these pieces as well as to works by contemporary Icelandic playwrights such as Oddur Björnsson and Njörður Njarðvík. Moreover, he composed the music to several productions by the Iceland Dance Company and the Frú Emilia Theatre Company.

Meanwhile, Ragnarsson made his mark as a composer of modern classical works, working freelance for most of the 1980s and 1990s; in 1988-91 and 1997-98, he received a composer’s salary from the Icelandic state, which allowed him to fully focus on composing. Amongst his many secular vocal works and religious choral music, an a-capella Mass in Five Movements, created between 1982 and 1989, deserves special mention. Ragnarsson also composed solo works for piano, flute, recorder, and organ as well as creating opuses for chamber ensembles. Moreover, he wrote several pieces for full orchestra, including a Concerto for Organ and Orchestra (1997).

After his research project on Jón Leifs at Cornell, Ragnarsson continued to devote much time and energy on familiarizing the Icelandic public with, what he thought, the man who should be considered the country’s national composer.

“Already as a student, it was my ambition to give the legacy of Jón Leifs the status which Grieg’s has enjoyed in Norway and Sibelius’ in Finland. Back in Iceland, I tried to accomplish this by publishing articles and encouraging orchestras to perform parts from his oeuvre, whilst I edited some of his unpublished works. In a way, I was acting as Jón Leifs’ impresario – though that is a strange thing to say given the fact that he died in 1968. Between 1990 and 1995, together with Sveinbjörn Baldvinsson and director Hilmar Oddsson, I worked on the script of a feature film based on the life of Leifs, Tears Of Stone. The soundtrack is a combination of elements from Leifs’ oeuvre, folk music, and additional compositions by me. The film was a big hit in Iceland and received prestigious awards abroad."

"Although the film is not a documentary, it immediately established Leifs as the most unique of Icelandic composers and at the same time put him in the front as a composer of international stature. Today, his music is being performed regularly and musicologists are doing research into his work. Though at one point I decided it was time for others to take over, I was totally occupied by him for the best part of two decades. In my family, we often joked that we should leave an empty chair and put an extra plate on the table for Jón Leifs at the dinner table, as he seemed to be a fully-fledged member of the family. Sometimes, I found it hard to think or talk about anything else!”

After the successful Tears Of Stone project, Ragnarsson composed the soundtracks to two more feature films directed by his personal friend Hilmar Oddsson, No Trace (1998) and Cold Light (2004). In another field, media, he chose the music for several classical music programs on Icelandic national radio as well as private radio stations for many years, whilst he also was a member of programming commissions for art festivals. On top of that, he engaged in writing notes for records and CDs and lecturing and publishing extensively in newspapers and magazines about music and cultural matters in general. Ragnarsson also served as a board member of the Icelandic Performing Rights Society (STEF) and the Icelandic Music Information Centre, whilst he was the chairman of the Society of Icelandic Composers (1988-92) and the president of the Federation of Icelandic Artists (1991-98).

In this last-mentioned function, Ragnarsson helped to gather support in cultural circles and in politics for establishing a new academy for the arts, the first art education institution at university level in Iceland. When the government finally gave the green light to this project, he was given the task to put the ideas into practice. The Listaháskóli Íslands or Icelandic Academy of the Arts (IAA) was founded in September 1998 and the first department opened in the autumn of the following year. Ragnarsson became the institution’s first rector. Meanwhile, the academy has five departments; art education, theatre and dance, design and architecture, fine arts, and, of course, music. The total number of students is about 450.

Being awarded with the epithet of Honorary Artist of the City of Kópavogur (2009)

“From a musician’s point of view, the academy was needed, because Iceland did not have an accredited conservatory at university level," Ragnarsson explains. "That is why we had to go abroad to obtain a bachelor’s or master’s degree in music. Perhaps even more importantly, the IAA project gave me the possibility to put my ideals about education into practice. I have always been very critical of the way European style conservatories have been run, where teachers expect to be addressed as Herr Professor and students focus on only a few narrow subjects. I was more inclined to take up the American tradition, where relationships between students and instructors are more informal and music students are encouraged to explore other fields of arts as well."

"When establishing the department of music, our motto was; no passports please. I did not want to focus on the differences between different fields of art – in music, for example, the difference between classical genres, jazz, and pop – but on talent, passion, and devotion. In the end, when an artist is about to set off on a career on a large scale, he has to focus on one subject only – true, but before that, to my mind, he needs an artistic education that covers as wide a range of subjects as possible. In its structure, with cross-fertilization between different cultural fields, the academy is quite a unique institution in Europe. Apart from putting in my own ideals, establishing the academy was all about not disappointing the politicians responsible and the artistic community who had entrusted me this responsibility; the education and examination had to be of the highest possible standard.”

Ragnarsson, who was awarded with the Knight’s Cross in the Order of the Falcon (1996), the Gríman Theatre Prize (2003), and the title of Honorary Artist of the City of Kópavogur (2009), left the IAA in mid-2013 after three consecutive terms of 5 years as its rector.

“The academy allowed me to implement my ideas about music education and culture in general more than I could have in any other position, but it was time to let someone else with a fresh approach take over. In fact, my plan was to leave after my second term in 2008, but when the economic crisis hit our country, the budgets in the cultural sector were cut down by some 25 per cent. Leaving at that point would have felt like desertion. These were difficult years, but gradually, the situation has improved, which allowed me – confident about the academy’s future – to step down. Becoming a freelance artist once again, I am able to devote more of my time to composing. During my years at the IAA, I felt I had only used about a quarter of my abilities as an artist. I'm hoping to make up for that in the years to come!”

EUROVISION SONG CONTEST

After Iceland’s debut in the Eurovision Song Contest (1986) with the up-tempo ‘Gleðibankinn’ by the trio Icy, the country’s second national final, one year later, was surprisingly won by a totally different type of song. Valgeir Guðjónsson’s composition ‘Hægt og hljótt’ was the opposite of the archetypical Eurovision song; a subtle, sophisticated ballad with atmospheric lyrics, performed by a young opera singer, Halla Margrét Árnadóttir – in 1987 just a student, but later to make a wonderful career as a professional opera performer in Italy. As such, ‘Hægt og hljótt’ ranks amongst the most original entries ever to have been submitted to the Eurovision Song Contest. When it won the Söngvakeppni Sjónvarpsins, the Icelandic pre-selection, there was no orchestration yet, but just a provisionary arrangement with piano and some string and flute lines recorded on keyboards written by Jon Kjell Seljeseth. Up to that point, Hjálmar Ragnarsson was not involved in any way in Guðjónsson’s song. How did he end up conducting it in the international Eurovision final in Brussels?

“To be honest, I could never have imagined going to Eurovision until just a few weeks before the competition took place in Belgium," Ragnarsson laughs. "Actually, the year before, when Iceland participated for the first time, I made a point of not watching it. Our entry was ridiculous and tacky. Many people believed we would win – a typical case of a small nation with an inferiority complex; we were going to show Europe how it is done! It must rank as the most absurd self-delusion of our nation ever. The more high-brow artistic community in Iceland, in which I was deeply involved, was totally against spending government money on this participation. Many of my friends believed we should not be doing Eurovision anyway. On the evening of the live broadcast, I went to a wedding celebration of friends of mine. Driving back home, it struck me that the streets were empty. Everybody in Reykjavík was glued to their television set. On my way back, I made an effort to take all detours possible to make sure the broadcast would be over when I would arrive home. I did not want to have anything to do with that stupid TV event at all! The lack of reflection about that song and that performance annoyed the hell out of me.”

Then, in March 1987, Hjálmar’s good friend Valgeir Guðjónsson won the Icelandic pre-selection as a composer with ‘Hægt og hljótt’. “Because of my involvement in cultural politics here in Iceland, I had some friends in the pop music sector as well. Valgeir was one. He was in some excellent pop groups from the early 1970s onwards and had proved himself as a talented songwriter. Our wives were quite close friends and so were we. When Valgeir’s song won the Söngvakeppni, I was pleased. Compared to the year before, I thought, we are doing something right now. This is sensitive and sincere; whatever placing we will get in Europe, we do not have to be ashamed of ourselves. But, you are right; I had no involvement in recording the demo version.”

“At that time, I was working in the National Theatre as a composer and music coach, preparing a large-scale production of a play by Garcia Lorca, Yerma. Then, there was this phone call from Valgeir. He was in trouble! With only days to go before the deadline when the scores to the international Eurovision Song Contest had to be submitted, he needed a new orchestration. From what I understood, he wanted more or less the same arrangement as in Jon Kjell Seljeseth’s demo, but now with real, classical instruments and more embracing strings. Initially, Valgeir had called upon another composer to write out the arrangement, but that turned into a disaster; it was too complicated, too contrapuntal, and somehow too academic. Valgeir had decided to throw it away."

Valgeir Guðjónsson, composer of ‘Hægt og hljótt’. Promotional photo, 1987

"When he, clearly distressed, asked me to help him out, I protested. The premiere of Yerma was quite close and the rehearsals were in full swing. In the end, I succumbed to his pleas – I wanted to do my good friend a favour. So there I was, spending a couple of nights writing a new arrangement. I wrote out the parts for all instruments by hand. It had to be done fast. The key was to allow the strings to come in from below and above in a way that they added to the atmosphere of the song without intruding its simplicity or the beauty of Halla’s voice. Then, we rushed into the studio to record the accompaniment with string players of the Iceland Symphony Orchestra. Even there, we only had a very limited amount of time to our disposal to make a decent recording. It was stressful! Luckily, I had a very good concert master in Szymon Kuran and everything worked out fine.”

With the recording of ‘Hægt og hljótt’ done, Hjálmar was eager to fully concentrate on the approaching premiere of Yerma, but songwriter Valgeir Guðjónsson had other plans. “I thought my job was finished. I had no idea I would be needed anymore. A couple of days later, however, there was Valgeir on the phone again. Now that I had arranged and conducted the studio version of the song, he felt I had an obligation to come to Brussels to conduct there as well. He said that the studio arranger and the conductor in the contest had to be one and the same person; later I found out that this was not necessarily true! Anyway, at that time, I felt Valgeir left me no other option. It was not that I was reluctant to go to Brussels, especially with a good friend such as Valgeir, but… this meant I was away from Reykjavík for an entire week! To make sure the rehearsals of Yerma in the National Theatre could continue, I had to find another musical coach to replace me. It could well have turned into a disaster, which, in the end, it did not – fortunately!”

Given his involvement in the avant-gardist artistic circles in Iceland in general, and especially because of his outspoken criticism of the Icelandic entry in 1986, nobody could have been more surprised about his involvement in the Eurovision Song Contest one year later than Hjálmar Ragnarsson himself.

“Indeed, it was surreal. Some of my friends from the artistic world could not stop making fun of this highbrow guy who was all of a sudden going to Eurovision. It was even a subject of satire on TV – yes, you can say my participation did not go unnoticed in Iceland. I was known for experimental music and demanding avant-garde; and now, on the bus taking us to the airport in Keflavík, I found myself quizzed by radio journalists putting a microphone to my mouth asking me about how I believed Iceland would do in the contest! Quickly, I struck up a bond with the two guys who provided the background vocals. They had a classical background as well. All three of us believed the contest was some sort of joke because our country had presented itself in such a foolish way in 1986. In spite of that, now that we were in it, we decided to give it our all.”

“In Brussels, we sometimes felt we had landed on a different planet. At some party to which we had been invited, I and my two friends loudly asked ourselves, “What on earth are we doing in this crazy place?” The atmosphere at the festival was very superficial and sometimes straightforwardly stupid. There were yellow press guys all around and you were offered gifts by sponsors at all times, such as perfumes and even toilet paper! We really felt out of place at moments like that. In our spare time, we tried to do some sightseeing in Brussels."

Halla Margrét backed up by Valgeir Guðjónsson at the piano; promotional photo (1987)

"On a positive note, we had a great time with the Israelis for the entire week of preparations. Our performances were quite close to each other in rehearsals and, for some reason, our delegations gravitated towards one another. The two singers (Datner & Kushnir - BT) were comedians and fantastic performers. Their choreography was great too and, though I do not speak a word of Hebrew, I thought the song was extremely funny. I was kind of convinced they would win the contest! Having studied at the Jewish Brandeis University in Boston and having performed at the ISCM World Festival in Israel, it felt special hanging out with these people, feeling these strong ties to Jewish culture in me. Their conductor (Kobi Oshrat - BT) was a great guy as well. In Iceland, his Eurovision winner ‘Hallelujah’ was a big hit. At the contest in Brussels, everyone knew he was the guy who had written that song.”

“In rehearsals, I found out soon enough that the Belgian orchestra was excellent. Our arrangement included just the string section, with some additional percussion and tympani, and we played it through a couple of times. The orchestra players told me they liked the score and my approach. Playing the orchestration really was the easiest part of the job. As far as I was concerned, we needed to focus on the stage presentation and on the quality of the sound. In the end, I found myself harassing the Belgian organisation with all kinds of questions. Actually, this should have been done by the team of RÚV, the Icelandic broadcaster, but they did not seem to be taking the contest too seriously, instead spending a lot of their time on shopping. I felt they should have asked for improvements in the camera work, demanding a more innovative approach from the Belgian director. Valgeir, who was on stage miming the piano, was not always there, being asked for all kinds of interviews and attending press conferences."

"In Brussels, I did not have as many social duties to perform as Valgeir, giving me the time to focus on the technical side. I worried about the mixing of the sounds of the orchestra and the background vocals. Apparently, I did not succeed in explaining to the sound engineers what the problem was – in the live broadcast, the background singers could hardly be heard at all. Probably, the RÚV team thought I was a nuisance, asking for all kinds of impossible details. It just goes to show how seriously I took the job now that I was involved.”

“You know what annoyed me most about the whole performance we did? That white piano! Valgeir’s piano on stage was white. How can you present a song in a serious way with such a kitschy thing on stage? I voiced my opinion on that as well, but I could not have my way all the time. Working with Halla Margrét was a nice experience. She was a likeable girl and I was much impressed by her vocal abilities, but she was very inexperienced and quite nervous. She relied a lot on me throughout the week – perhaps because she knew I had this background in classical music. In contrast to what I expected, I found there were some very good songs and vocalists amongst the other participants. Umberto Tozzi from Italy stood out as a performer, and his song ‘Gente di mare’ was great as well. The French song (Christine Minier’s ‘Les mots d’amour n’ont pas de dimanche’ - BT) did not get that many points, but I thought that one was pleasant as well.”

In the live show, when Ragnarsson was introduced as the conductor of the Icelandic entry and took his bow, he was visibly nervous, his hands shaking as he lifted them. Hjálmar remembers these instants well.

Halla Margrét (right) with the Netherlands' performer Marcha at a cocktail party - Brussels, Eurovision 1987

“I took more time than any other conductor that evening before counting the orchestra in. While I was in the dark, waiting for the host to introduce me, I was suddenly aware of the immense audience of such a programme. How many people would be seeing me... 200 million, 300 million perhaps? In avant-garde and radical circles, on moments like this, people do striking things on stage, making a point to prove that they are nonconformist; for example by cutting off a sleeve or exposing themselves in an offending way. Suddenly, I felt this weird urge to make a statement as an artist. This was an opportunity! However, debating with myself, I felt I could not do that. After all, this Eurovision participation was the project of Halla and Valgeir – who was I to destroy that? The moment the camera turned to me, I was just recovering from that thought, which stayed with me until the moment I started to conduct. From then on, it was down to business and being a professional again.”

In the voting, Iceland only managed to collect only 28 points, finishing in a 16th place in a field of participating countries. “Admittedly, we expected more," Ragnarsson admits. "We never believed we would win, but we thought jurors would sympathise with our song and award it with some decent points here and there. When it comes to explaining why they did badly in a Eurovision voting, many artists resort to stupid conspiracy theories, but I am not one of them. Perhaps, in the context of a Eurovision competition, ‘Hægt og hljótt’ was not spectacular enough – a little underwhelming."

"Obviously, Johnny Logan, who won it, had a big ballad, ‘Hold Me Now’. He probably drew away some votes that would otherwise have gone to our ballad. Frankly, I cannot say ‘Hold Me Now’ was a good winner. Though Johnny Logan gave a great performance, at the same time exposing all the pain in him and being very charming, the song itself is not going anywhere; it is not much of a composition. It does not have a climax and the build-up is extremely simple. It is a very small statement, in a way. I am sure it was Johnny’s charisma which won him the trophy.”

“My best memory of the entire Eurovision week is of the after-party. All of the week, there had been this superficial atmosphere of throwaway entertainment… lots of fuzz about simple songs. Now that the voting was over, all artists became everyday persons again. Suddenly, there were no photographers following Halla around any longer. All the sugar and hupla surrounding the competition was gone and everyone started behaving in a normal way. That is when you can start communicating, having sensible and interesting conversations. This kind of melancholic atmosphere when the curtains have been drawn and the concert is over is something I particularly like. We met some interesting people after the show was over in Brussels. I remember having a chat with host Viktor Lazlo. Saying that we were disappointed? Actually, no! We finished the project in a way which we were all happy with and now it was time to go home!”

Back in Iceland, Hjálmar got back to work in the National Theatre. “My friends in the theatre prepared me the honour of a small act; a parody on my participation as a conductor in the contest. It was just between rehearsals on the large stage, a little performance for me and a few others - very nice! Some of my artistic friends, however, did not speak to me for weeks! Especially one composer did not like what I had done and criticised me for having participated in this silly event; I who had thought of my involvement in the contest as a radical act! Indeed, without wanting to make too much of it, to my mind, it was a small message that the walls between elite culture and mass entertainment could be torn down. Looking back on it, I am proud of what we did. We came to Brussels with a great song and we performed it in a professional way that everybody in Iceland could be proud of. It did not matter that we came 16th, because we had presented ourselves in a credible and dignified manner.”

Halla Margrét with the two singers of Nevada, Portugal's representatives at Eurovision 1987

OTHER ARTISTS ABOUT HJÁLMAR RAGNARSSON

So far, we have not gathered comments of other artists who worked with Hjálmar H. Ragnarsson.

EUROVISION INVOLVEMENT YEAR BY YEAR

Country – Iceland

Song title – “Hægt og hljótt”

Rendition – Halla Margrét Árnadóttir

Lyrics – Valgeir Guðjónsson

Composition – Valgeir Guðjónsson

Studio arrangement – Jon Kjell Seljeseth / Hjálmar H. Ragnarsson

(studio orchestra conducted by Hjálmar H. Ragnarsson)

Live orchestration – Hjálmar H. Ragnarsson

Conductor – Hjálmar H. Ragnarsson

Score – 16th place (28 votes)

SOURCES & LINKS

- Bas Tukker interviewed Hjálmar H. Ragnarsson in Kópavogur, Iceland, July 2012

- A book about Iceland’s involvement in the Eurovision Song Contest: Gylfi Garðarsson, “Gleðibankabókin”, ed. NótuÚtgáfan: Reykjavík 2011

- Hjalmar Ragnarsson’s master thesis: “Jón Leifs, Icelandic Composer: Historical Background, Biography, Analysis of Selected Works”, Cornell University: New York 1980 (unpublished)

- Several of Ragnarsson’s publications were given an English release, including the textbook “A Short History of Icelandic Music to the Beginning of the Twentieth Century”, ed. ICE – MIC, 1984

- Photos courtesy of Hjálmar H. Ragnarsson and Ferry van der Zant

No comments:

Post a Comment