The following article is an overview of the career of Swedish trumpet player, composer, arranger, bandleader, and producer Lars Samuelson. The main source of information are three interviews with Mr Samuelson, conducted by Bas Tukker in April 2024. The article below is subdivided into two main parts; a general career overview (part 3) and a part dedicated to Lars Samuelson’s Eurovision involvement (part 4).

All material below: © Bas Tukker / 2024

Contents

- Passport

- Short Eurovision record

- Biography

- Eurovision Song Contest

- Other artists about Lars Samuelson

- Eurovision involvement year by year

- Sources & links

PASSPORT

Born: August 4th, 1935, Sundbyberg, Greater Stockholm (Sweden)

Nationality: Swedish

SHORT EUROVISION RECORD

Lars Samuelson took part as a conductor in the Eurovision Song Contest on three occasions, leading the orchestra for the Swedish entries ‘Judy, min vän’ by Tommy Körberg in 1969, ‘Jennie, Jennie’ by Lars Berghagen in 1975, and ‘Satellit’ by Ted Gärdestad in 1979. Many years later, he was also involved in the festival as the producer of Roger Pontare’s Eurovision entry ‘When Spirits Are Calling My Name’ (2000). Moreover, Samuelson was the musical director of the Swedish Eurovision final, Melodifestivalen, on four occasions in the 1970s, as well as being one of Sweden’s jurors in the 1973 international final in Luxembourg.

BIOGRAPHY

Lars Gunnar ‘Lasse’ Samuelsson was born in 1935 in Sundbyberg, on the outskirts of Stockholm. “I come from a working-class family; nothing special, normal working people. My father was a typesetter at a newspaper in Stockholm. At that time, when I was young, there were two options open for young guys in their free time: sports or music. Initially, I was a sports man, but in the apartment block where our family lived, there was someone able to play an instrument in every house. That was quite unusual. This awakened my interest. Then, when I was sixteen, I happened to walk by a store of second-hand musical instruments. In the shop window, my eye was caught by a trumpet. I fell in love with that instrument instantly. It was very cheap, but still I couldn’t pay it. I had to borrow money to buy it. From that time onwards, my life started revolving around the trumpet. I went to music school to take lessons. By then, I was already out of regular school. I had a job as a designer at the same newspaper where my father was working, but there was no passion in it for me. Every free hour was spent on the trumpet.”

“In those days, jazz music was what pop music is today. All the young guys in our apartment block were listening to jazz. My idol was Stan Kenton; his big band was the most modern and innovative. My first teacher at the local music school happened to be a very good one; his name was Ingvar Cederberg. He was a military trumpet player originally from Scania in the south of Sweden. He helped me a lot. I wasn’t a naturally gifted trumpet player; I had to practise for hours a day to improve my skills. Meanwhile, I was playing in all kinds of amateur bands and orchestras. Gradually, I noticed I was getting better and better – not only technically, but also in terms of reading music.”

“At age nineteen, I was called up to perform my year of military service. I was stationed in Ystad in the far south of Sweden. Although my teacher had good connections in the army, he didn’t manage to persuade my officers to allow me to join the army band. Even when he asked me if I could at least rehearse with them, the permission wasn’t granted. That was a blow. I was to be a regular soldier. In the army barracks, I continued to practice on my own – two hours every evening. Until that time, music had just been a hobby, but I was getting into it more and more. During that year in Ystad, my thoughts started gravitating towards studying music. My parents didn’t agree with me. ‘Don’t be a musician,’ that’s what they told me every time. Perhaps that’s why I decided I wanted to go ahead with it anyway! Being a musician would be my dream come true. After coming out of the army, I decided to go ahead and study trumpet at the Royal Music Academy in Stockholm.”

Lars (front row, second from left) in an orchestra of music students, led by his first teacher Ingvar Cederberg (in black, middle of front row), c. 1949

“In the following five years, my life was subdivided between the academy and playing in all kinds of dance bands at the weekend. Before long, I was earning enough of an income from music to give up my job at the newspaper. One of the orchestras I played in was led by Seymour Österwall. He formed a new band of young musicians every year and toured Sweden for the summer season. In fact, the guy I replaced in the brass section was Benny Bailey! Many good musicians started their careers in Österwall’s band, but the music you got to play with him wasn’t very interesting. This was pure entertainment music. You just played with him for a year to build your reputation and then you moved on. Around that same time, I also played in the theatre orchestra of Eva Engdahl. Eva was the mother of Georg Wadenius, the future guitarist in Blood, Sweat & Tears.”

“In 1958, I joined the Malte Jonsson Band in Gothenburg. I must have played with him for the best part of a year. Playing with Malte Jonsson was one step up from Seymour Österwall. This was a big band and Malte himself was interested in more modern types of jazz music. We did a radio concert every week and the band was also playing in studio sessions regularly. The first one I was involved in was when we were booked to back up The Delta Rhythm Boys, a famous American vocal group. That first time in the studio, I was intimidated – not because I didn’t know what to do or because the music was difficult, but because I realised how important it was; you knew that many people were going to listen to the recording. I really felt the pressure of the occasion.”

“After playing with Malte Jonsson for a season, I returned to Stockholm to continue my studies at the academy. Coming back, I noticed how much more seriously I was taken by fellow musicians. They respected you when you told them you were studying at the academy, but once they found out you had been playing with Malte Jonsson, they were more impressed. The band had a good reputation. Apparently, I was on my way to becoming a good musician! Even though I was still a student, I was regularly called upon to do replacement jobs with the radio orchestra of Thore Ehrling – and later also Harry Arnold’s radio big band. Apart from that, I became a regular player at studio sessions as well. I was very interested in studio work. Those gigs were well paid and it was a confirmation of your standing in the business. You were only asked if others knew you were any good.”

“My main teacher at the academy was Allan Olsson, a tenor trumpet player at the opera house in Stockholm. He was a very good guy with an open mind to all music. He didn’t look down upon me for playing jazz. You couldn’t study jazz music at the academy back in those days, but I must say I was fortunate to receive such a thorough classical education. I loved classical music, but I never seriously considered playing in a symphony orchestra. First, the music was too difficult to play for me. Besides, as a trumpet player in a classical orchestra, you’ll get to play just five minutes on average in two hours of rehearsal. The rest of your time is spent counting bars. It would have bored me after a while. My wish was to play a lot and get better, which is what I did in all those dance bands. Without the academy background, though, I couldn’t have had the career I had. I didn’t take the final exams, but nobody could take away from me those five years of classical trumpet lessons and the background in theoretical subjects, mainly harmony. Given that I turned to arranging and leading bands later on, this was very important.”

“The following years were subdivided between playing studio sessions and working as a live musician. The main band I played in during the early 1960s was the Putte Wickman Orchestra, which was a big band. I was a founding member and I stayed with Putte for two or three seasons. Putte was a brilliant clarinettist, but he was a special guy to work with. Whenever we went to a gig, all the musicians travelled on a big coach, but Putte preferred driving there with his own car. However, he was an awful driver. He was always speeding and had accidents regularly. I remember two or three times, on our way home after a concert, we had to stop on the roadside because we found Putte’s car smashed up in the woods. He then had to hop onto the bus after all and that’s how he got back to Stockholm. Putte might have been a little crazy, but I had a fun time playing with him. Like me, he had become a musician against the wishes of his family. He practised a lot just to prove them wrong – and that’s part of the reason why he became so big and famous.”

“In 1963, I formed my first own band, the Swing Sing Seven. This was a typical Friday-Saturday-Sunday entertainment band. For some two or three years, we played at Nalen, a famous restaurant in the heart of Stockholm. To broaden our repertoire, I started writing little arrangements myself. It wasn’t long before I could put my fledgling arranging skills to use in the studio as well. One day, I was booked as a trumpet player for a session which was to be conducted by a German arranger. He should have come to Stockholm, but he didn’t show up – and then someone asked who could take over the job from him. I raised my hand. I wrote the arrangements and guided my fellow musicians through the session; and it went well.”

Lasse (far left) as part of an orchestra accompanying Danish bandleader and comedian Boyd Bachmann (centre) on a Swedish tour, early 1960s

“That was the start of my career as an arranger. From then on, producers knew they could book me to write scores for them; and there was a lot of arranging work in those years. In the beginning, I mainly copied arrangements of American and German songs which were covered by Swedish singers. Basically, I just plagiarised the work of arrangers from overseas. This was an essential step in order to learn how to go about it. Meanwhile, I was doing a little studying by myself to get to know the range of the various instruments, but the main learning school in terms of arranging was listening to records from abroad and writing out the parts. You first have to learn what others have written before you can invent something of your own; I firmly believe in that. As a trumpet player, I had done the same – copying the style of older trumpet players who I thought were good. Yes, plagiarism is a requirement in music if you want to progress. Others may disagree with me, but that’s certainly how I learned my trade!”

“Most of the time, copying those foreign songs was easy work – German Schlagers especially weren’t usually very hard to write an arrangement to. Still, the work could be tricky. I was regularly asked to arrange American songs which had been recorded with a big orchestra in the US – but the budget only allowed a group of ten session musicians. This was where some creativity was involved! After a while, I was given the opportunity to try my hand at writing original arrangements as well. I was slowly starting to understand what I was doing, you know! I learnt a lot from Stan Kenton and the West Coast arrangers; they were my inspiration, but generally I simply followed my intuition. Writing arrangements is essentially about improvisation and imagination.”

“In 1965, I was commissioned to put together a band to accompany a young Swedish rock singer, Jerry Williams (pseudonym of Sven Erik Fernström – BT). It was an eight-man band called The Dynamite Brass. I wasn’t particularly fond of rock ‘n’ roll music, but you have to live, you know! It was obvious there was a development happening in those days. Interest in jazz music was on the wane. All the young guys were playing rock and pop. As a musician, you have to move with the times. I was one of the first jazz musicians in Sweden to play with rock ‘n’ roll guys. More important than the style of music we were playing was the fact that I got along well with Jerry Williams. When you’re working with fellow musicians for months on end, you have to like them on a personal level. I don’t like working with everyone, but Jerry was a nice guy. We always had a good time together.”

Single release of the Dynamite Brass with Jerry Williams, with Lars Samuelson as bandleader (third from right), 1967

“After a while, The Dynamite Brass was also invited to perform with others. Swedish Radio hired us to play in live radio shows nearly every week, working with guest artists. We even accompanied a very young Elton John on his first tour abroad. He wasn’t a star yet, but at least I can say I wrote band arrangements for Sir Elton John! We also accompanied Siw Malmkvist in Munich, where she had been booked to perform in a nightclub for half a month. This wasn’t rock ‘n’ roll music at all, but my band consisted of experienced session musicians who could play in virtually any style you asked of them. During our time in Germany, we also did some TV gigs with Siw. She was a really popular artist in Germany at the time. Siw was very nice to work with. Her skill at learning to sing in foreign languages was exceptional. Her secret was that she wasn’t afraid to make mistakes. Siw wasn’t what you call a perfectionist. She was just having fun. That made her look so easy-going and relaxed on stage.”

“I also did a lot of session work for Siw in those years – but then I worked with many artists… Alf Hambe, Svante Thuresson, Siw Malmkvist, Tommy Körberg. In fact, there must have been many more. When I think back to those years, there is a big black hole in my memory. I don’t remember much of it. Over the years, I literally wrote thousands of song arrangements. It wasn’t that I was a very talented arranger – I would say I think some ten percent of my charts are any good, no more. There were many guys in the business who wrote much more refined scores. My main quality was that I was fast. One day, I received a telephone call from Lee Hazlewood, an American country singer who was living in Sweden. He called me at 8am asking me to write an arrangement for him. It took me no more than an hour, a copyist wrote out the parts for me, and then we rushed to the studio… and by 11am, the song had been recorded. In just three hours!”

“For some five or six years, I played live on stage with The Dynamite Brass at night, while working as a studio musician during the daytime. I was the guy who never said no. Whoever called me for a score, it didn’t matter – I always said, ‘Yes, I’ll do it.’ Somehow, writing arrangements came easy to me. Apart from all that, I also released a couple of solo recordings as a trumpet player. A producer asked me to record some material; and also in this case, I said yes, because as a session musician, you do what’s asked of you. I did my best, but I’m not very proud of those instrumental releases. I never had the ambition to be a trumpet soloist. I have always been much more of an orchestra guy, a team player. As you can imagine, these were incredibly busy years. Looking back, I worked much too hard. I liked my job, but I wasn’t looking after my family well. My wife was very good to me. She must have been very lonely at times. I’m not proud of that.”

With jazz singer Lill-Babs (1973)

“Apart from all the other things I did in those years, I was also part of a group of musicians who were regularly called upon by Swedish Radio to perform in jazz programmes. Not long after the disbandment of the Harry Arnold Orchestra, which had been the radio big band for some years, the Swedish Radio Jazz Group was formed (in 1967 – BT). It consisted of eleven musicians and I must have been part of it pretty much from the outset. Some years later, this group was the nucleus of the new SR Big Band. There were some great musicians in it – the greatest arguably being Arne Domnérus, who played the saxophone and the clarinet. He was the nominal leader of the band, but he never conducted it. There was no fixed conductor.”

“After I had gained a little bit of a reputation in television circles for doing Eurovision with Tommy Körberg in Madrid in 1969, I became in demand to lead the big band for television shows. Producers were asking for me. If additional musicians were required, I called upon my buddies from the record studio. This band was the strongest I played in. For most of the performances, I simply played in the trumpet section at the back of the band. I only conducted them when the music required a conductor. For most big band music, you just have to start the band – and then, if you have a good rhythm section, they will pretty much lead the others from that point on.”

“For television, we worked in different set-ups; it depended on what the production team was looking for in a programme. In 1973, I formed a small combo for a show produced by Torbjörn Axelman, with Lill Lindfors and Lee Hazlewood starring. It featured songs written by Lee for which I wrote the band arrangements. That show (called NSVIP, ‘Not So Very Important People’ – BT) went on to win the Rose d’Or in Montreux. One of the other programmes which had been submitted for consideration in Montreux was a show featuring Frank Sinatra! For the rest of his life, Lee Hazlewood told everyone that he had beaten Frank into second place! He was very proud of that.”

Rehearsing with the Swedish Radio Big Band and singer & TV host Östen Warnerbring (mid-1970s)

“Another programme which I conducted was Oppopoppa, originally a radio show, but later redeveloped for television. It involved outdoor concerts on stages across the country with the big band and guest singers. The producers managed to lure many international artists to come to Sweden to perform with us. Generally speaking, I liked those TV gigs. The level of musicianship involved was high. I always preferred playing anonymously as a trumpet player in the band rather than being up front conducting them. In those cases when I was conducting, I was happy that I was always standing with my back to the audience. One time, while I was busy working on a set of arrangements at my home desk, my wife cut my hair. As I remember, the result wasn’t very good; and I had to do a TV show that night! I looked a bit weird with this new hairdo – but because the cameras were only filming my back, it didn’t matter anyway. For me, doing television was never about being famous. I just wanted to work with my fellow musicians, enjoying the music and creating a good sound.”

“Some of the international artists we worked with in radio and television programmes came back to go on tour with our big band. These included Jerry Lewis and Sammy Davis Jnr. Sammy Davis had only been convinced to come to Sweden because Lena Horn told him that our band was so good. We toured the Scandinavian countries with him for many years. Sammy was an excellent professional; one of the best I worked with. Off stage, he mostly preferred to keep to himself. We usually travelled to concerts by train. In those cases, Sammy had a cabin of his own. When it was winter, the temperature in it had been heated up to 40 degrees at least. He hated the Scandinavian cold, but he came anyway! Artists like Jerry Lewis and Sammy Davis usually brought their own arrangements, which they guarded very carefully. After every concert, the scores were gathered and locked away in a big suitcase. They didn’t want others to steal the charts written for them by their American orchestrators.”

“Some time in the mid-1970s, I was asked to join James Last’s orchestra on a tour in Belgium and England. I just did the one tour with Hansi, as we called him, but I played the trumpet on an album he recorded around that same time as well. He already had one Swedish trumpet player, Leif Uvemark; and, when there was a vacancy in the trumpet section, Leif must have mentioned my name. Most of the other musicians were from Germany and they had a choir from England. Of course, James Last’s music wasn’t jazz, but he was a great arranger and it was a very good experience to play with him. Hansi looked after his musicians well. When we were rehearsing, he always made sure there was a bar where we could hang out during our breaks. The hotels we were staying in were the very best, the restaurants the most expensive, and the pay was good. These weren’t things I was always used to as a musician.”

On tour with Sammy Davis Junior, mid-1970s

“Meanwhile, I continued working as an arranger with pop singers in the first half of the 1970s. Some of them, guys like Björn Skifs, Tomas Ledin, and Ted Gärdestad, were artists of a new generation. Those rock guys respected me for the work I had been doing with Jerry Williams. I was a little younger than most of my fellow arrangers, but I was some ten years older than most of those new rock kids. Some of them looked up to me as some sort of father figure. I distinctly remember Tomas Ledin coming to me and playing some of his songs on the guitar. I thought he was good and decided he deserved a chance. Tomas’ first two albums, with which he made his breakthrough, were produced by me and released on the RCA label.”

“A singer with a more conventional repertoire whom I also accompanied on her first steps as a solo artist was Titti Sjöblom. She was the daughter of Alice-Babs and had recorded some things as a child, mostly with her mother, but the first album she did in her own right was arranged by me (in 1971 – BT). In fact, Titti picked me as her arranger. I subsequently did two more albums with her and our working partnership lasted for many years longer. In 1975, I accompanied her to Bulgaria, where she represented Sweden in the Golden Orpheus Festival. I also did a similar contest in Romania once. All those countries in Eastern Europe had their own song festival. Titti was a pleasant girl to work with. I really liked her. She had a good reputation which she fully deserved.”

“In 1973, I founded my own record company, Four Leaf Clover. Sometimes I was approached by young artists who I felt were really good, but didn’t get the opportunity with one of the established companies. That’s what made me think I could be the one to help them. One of the early examples was the guitarist Janne Schaffer, whose first album was released by my company. Of course, I also liked jazz music a lot. There was an American trumpet player and bandleader, Thad Jones, who came to Sweden to play with the SR Big Band. Thad liked the orchestra so much that he asked if he could write arrangements for them. I agreed immediately and that’s where the record comes from; the radio recordings the big band did with Thad. That album (‘Greetings And Salutations’ – BT) was nominated for a Grammy in the United States. It didn’t win the Grammy, but it was a success in itself that a release of this little, new company of mine was in contention for such an important prize.”

Conducting a studio session with a group of string players for Titti Sjöblom's debut album in 1971

“As a producer, I never told the artists I signed what they had to do. I signed them because I liked their music and their ideas. I just used my ears – and my ears told me if the music was good. My weakness was that I didn’t know anything about the business part of recording. Generally speaking, the record company wasn’t a commercial success, though it was on an artistic level. For me, music was always number one. I was really happy with the material we were releasing. By focusing on jazz, however, you knew in advance that the potential number of record buyers in Sweden wasn’t that high. My biggest mistake was that I hadn’t foreseen I would lose most of my arranging work for other companies. They were afraid I would lure away their artists to my own company – and I lost those record labels as customers as a result. They found other arrangers to replace me. This cost me a lot of money!”

“Of course, I still had my work for radio and television. One of the most interesting projects I got to work on in Swedish Radio was the Nordring Festival. I was conductor of the Swedish entry four times (Groningen 1974, Oslo 1975, Inverness 1976, and Dublin 1979 – BT). The event was held in a different country every year and all the radio stations taking part brought a programme of 45 minutes of music. I was asked to do Nordring by radio producers here in Stockholm. They brought their ideas for a programme and I wrote the arrangements. I can tell you it took a lot of time to write a 45-minute arrangement! But it was always nice to work on, because the music was so good. I have particularly good memories of our 1979 entry, which had Janne Schaffer on guitar and Arne Domnérus on sax. It was a medley of Swedish folksongs done in a jazzy way; a really interesting programme.”

“The scariest thing about Nordring was having to conduct a professional radio orchestra with a large string section. The first time I took part was in 1974, when the festival was held in Groningen, but the rehearsals with the Netherlands’ radio orchestra, the Metropole Orchestra, took place at the broadcasting house (in Hilversum – BT). I’ll never forget the moment I came in for that rehearsal. While I was waiting, I saw the Belgian conductor at work. He counted in the band – but they didn’t play! Perhaps he had been unkind to them before I came in? Perhaps he had made some obvious mistake? At any rate, the musicians felt he wasn’t up to the standards they expected from a conductor – and in the end, he had to go… and then I was next to rehearse with them! I was nervous, I can tell you that. What was I to do? I’m aware that I’m not a good conductor. Before I started, I decided to explain that I’m not a professional conductor, but that I was confident that we could do a good job together if the musicians were willing to help me. In other words, I tried to get them on my side, especially the concertmaster, who I asked which gestures would be most helpful when working with the string section. That’s how I made it work in the end. Looking back, I regret that I never took conducting lessons, because they could have helped me getting more respect from the orchestras I worked with.”

Samuelson at Nordring 1976 in Inverness with the three Swedish representatives, Olof 'Olle' Thunberg, Svante Thuresson, and Marianne Kock; Olle Thunberg is the father-in-law of opera singer Malena Ernman and grandfather of climate activist Greta Thunberg

“The atmosphere at a Nordring Festival was much better, much more relaxed, than at Eurovision. At Eurovision, artists were always surrounded by representatives of their record companies. There were lots of journalists around. You could just feel the pressure being put on the singers. At Nordring, this wasn’t the case; it wasn’t a commercial event. For a week, you were just away on a trip abroad with a nice group of fellow musicians – and I was good friends with the singers who took part for us; guys like Östen Warnerbring and Svante Thuresson. We weren’t even that much aware that it was a competition. It wasn’t important who won it. The main thing was that you got to do a programme of interesting music which was broadcast in all participating countries. That was the main thing. Yeah, it was great. It’s a pity they stopped organising this festival.”

“In Sweden, the best TV programme I was involved in was I morron e’ de’ lörda’, which was a jazz music show with the SR Big Band. It ran for some five or six seasons in the second half of the 1970s into the early 1980s. The host, Östen Warnerbring, was a jazz musician himself and he did a good job on it. I conducted the band the way I preferred – simply from the trumpet section at the back of the stage. For each programme, I was excited to find out which guest artists from abroad the production team had invited. Over the years, we played with Anne Murray, Georgie Fame, Rich Matteson, Dexter Gordon, and many others. The budget must have been huge. It could be hard to work with all those stars, but most of them were very friendly. We started the rehearsals at 10am. Each programme involved at least ten new arrangements; and then we did a live recording in the evening with an audience. There was some pressure, but the music was at the centre of the programme – and I liked that.”

“One of the later programmes I did with the SR Big Band was in 1983, when the Gröna Lund amusement park in Stockholm celebrated its 100th anniversary. There was a huge open-air show, which was broadcast live on TV – and my band accompanied all the artists who had been invited. One of them was Tina Turner. I still remember how the producer walked up to me, saying simply, ‘Here you have a cassette with the music – now you go and write the arrangements for her.’ She did a set of six of her most popular songs, and I wrote all the scores for the band and the backing choir. I had never met Tina Turner before. In rehearsal, it turned out everything was ok, which I was very happy with. She proved to be easy to work with; a very nice girl.”

Lasse (far left) leading the SR Big Band the way he preferred it; from the back (1974). The musicians in the front row, from left: Erik Nilsson, Jan Kling, Claes Rosendahl, Arne Domnérus, and guitarist Rune Gustafsson; second row, from left: Lars Olofsson, Torgny Nilsson, and Bengt Edwardsson

“In the 1980s, when Swedish Radio decided to get rid of the big band, I did quite a lot of work as a composer of advertisement jingles and documentaries. I also wrote the score to a film called Raskenstam, a comedy directed by Gunnar Hellström. Agnetha Fältskog was one of the actors in it. Gunnar came back from the USA, where he had directed several episodes of Dallas. He personally asked me to compose the soundtrack to his film. He had his ideas about what he wanted the music to be like. Writing the score wasn’t that difficult. I received a list which provided detailed information on how long each piece of music had to last – and so I did just that, following Gunnar’s instructions. It wasn’t that much different from writing arrangements to pop songs.”

“Meanwhile, I was putting a lot of energy into my record company Four Leaf Clover. In the 1980s, I released several LPs done with my old band leader Putte Wickman, as well as producing records with trumpet player Rolf Ericson. At the start of my professional career as a trumpet player, Rolf had been one of my idols. Having played with Duke Ellington and so many other greats in the US, he had all the qualities to be a soloist in his own right, but he had always been too shy. He was just a musician; the only thing he liked to do was play the trumpet – and he could play whatever you wanted him to. It felt gratifying to give him the opportunity to finally record some interesting solo work. The first recording I did with Rolf was done on the Sonet label, although it was my production – and then I signed him for my own company for the following releases. I’m particularly proud of those records and I still listen to them quite often.”

“It wasn’t just guys from the older generation I signed on my label. Some time in the first half of the 1990s, I had been booked to do a performance with Arne Domnérus’ trio down in Malmö. On the night, we shared the stage with a local band, the Monday Night Big Band. Listening to them, I was impressed with the performance of the pianist, a young man called Jan Lundgren. I asked him if he was interested to do a solo record. That’s how I became the producer of his two first albums, which were very good – and then a bigger company came along and signed him. That was the fate of Four Leaf Clover; whenever an artist was successful, he was offered more money by a rivalling company. I accepted it as a fact of life. I’m happy to know that I stood at the cradle of the careers of quite some good musicians. Jan Lundgren is now a very successful pianist in Sweden and across Europe.”

Samuelson with (from left) Danish-Swedish arranger/bandleader Julius Jacobsen, jazz pianist Gunnar Svensson, and Thore Ehrling, longtime conductor of the SR Big Band (c. 1979)

“Also in Malmö, I worked with the local Fire Brigade Orchestra for about a decade. Most musicians in this big band were amateurs, but they were really good. During the summer season, they performed with popular Swedish singers – and for the arrangements, they turned to me. I wrote some 400 arrangements for them. They usually performed with a drum major up front, so I didn’t conduct them very often. On one occasion, when they took part in a military tattoo in Hanover in Germany, they invited me to come over and conduct one song with them.”

“After the turn of the century, I allowed my work pace to slow down a little bit, although I still took on some arranging projects, including the comeback album of Nina Lizell. Then, in 2006, all of a sudden, I received a phone call from Las Vegas. It was my old friend Lee Hazlewood, the country singer who I had worked with in Sweden thirty years before. He told me that he was terminally ill. He wanted to record a last album and he wondered if I was interested in writing the orchestrations. Of course I agreed. I’m a little proud of this – I mean, Lee was a big guy in the States. He had worked with Nancy Sinatra and Duane Eddy. He could have asked anyone to arrange the album for him; there are a lot of good arrangers in America, but instead he thought of me. We had worked together in the recording studio and on television shows in the 60s and 70s. I had also helped him with some film music. Apparently he was happy with what I had done for him in the past.”

“Most of the music was recorded in Stockholm with Swedish musicians. Because Lee’s French publisher wanted two French girls to sing backing vocals on the record, we spent some days in Paris – but then Lee decided to cut them off the final mix. I don’t know what happened exactly, but they may have asked for too much money which Lee wasn’t willing to pay. For the release of the record (entitled ‘Cake Or Death’ – BT), I flew over to Vegas. Lee passed away not so long after that. I’m quite happy with the work I did on that album. It was the last international production I was involved in as an arranger.”

Conducting a one-off performance with the Munkfors Big Band and guitarist Janne Schaffer (1980)

“The last time I did a concert must have been six or seven years ago (with the interview taking place in 2024 – BT) when I accompanied Georgie Fame on stage in Linköping. Georgie is an old friend who I worked with a lot in the old days. After that gig, I came home and I’ve never opened my trumpet case since that day. I was happy with the way I played, nothing wrong with that – but afterwards I was just feeling so tired. Around that time, my wife fell ill and her health declined in the following years. She passed away in 2023. Since then, I’ve been feeling pretty empty. Last week, a big band in Stockholm asked me to rehearse them. I doubted if I should do it; in the end, I did it, but in fairness I think I’m too old now to tell musicians what to do. Somehow, the interest isn’t there any longer. I’m feeling sorry about that, but what can you do?”

“This doesn’t mean that I spend my time doing nothing. These days, I listen to a lot of old master tapes and digitalise them – radio tapes and studio tapes of my record company Four Leaf Clover. It’s really enjoyable work, because there were a lot of good concerts and good musicians I got to work with. Maybe some of those recordings can still be used. There are enough of them to keep me busy for the next ten years – and this in spite of the fact that we haven’t released anything in the last twenty-odd years. Nowadays, it’s so funny to note that old records which I released on my label back in the 1970s are discovered by new audiences. In 1976, I did a live album in Stockholm with an American folk singer called Odetta. She once performed with Harry Belafonte. Recently, all of a sudden, that album has been getting a lot of attention on Spotify. The advantage of the Internet is that the music you recorded decades ago can now be reached with a few mouse clicks by listeners all over the world. Don’t you think that’s great?”

“Sometimes, I listen to contemporary jazz. Some of it is good, but I don’t like everything. The musicians nowadays are usually much better educated than we were. There are excellent jazz academies. Technically speaking, I wouldn’t have been able to compete with most young jazz musicians, but many of them seem to want to prove in every single concert that they can play a lot of notes very fast and in an extremely high pitch. Somehow, the feeling isn’t there. The older generation of jazz musicians used to take a breath in between their phrases. Today, you’ll find musicians who just play and play without taking a break. They are too much for me. Perhaps they just need a little more time. It usually takes quite long to find your true personality as a musician.”

Lee Hazlewood's last album 'Cake Or Death', released in 2006, was orchestrated by Lasse Samuelson

“When I think back over everything I have done in my life as a musician, it has been more than I could have dreamt of as a young man. I’m so happy with all the things that I’ve done. In retrospect, I’ve been lucky to be born in Sweden, which had one of the best jazz scenes in Europe. Many American musicians came to Sweden and Swedish musicians worked in America and then brought back their experience. As a result, the level of musicianship was very high. I worked with many good musicians. Then I’ve had the good fortune of being able to work with the SR Big Band, with which I did so many excellent programmes and concerts. I pretty much fulfilled all my ambitions as a musician. It didn’t matter if I was trumpet player number four or standing in front of the band conducting them. I was happy when I could work with my colleagues and play. Yes, I’ve had a good life.”

“If there’s one regret I have, it’s that I didn’t compose that much. I wrote a little film music and some advertisement jingles, but apart from that the only music I wrote were B sides. When a producer wanted to record a single with a singer, he needed a second song to fill the flipside. If I was the arranger, he often asked me if I could write a little tune. As an arranger, you tend not to think that much of your own music. I wrote arrangements in every style they wanted of me; rock, pop, jazz, anything. You could say that my brain was split – split between all those genres. The focus wasn’t there to sit down and compose my own music. I would have liked to try my hand at writing children’s songs, a musical, or some good jazz tunes, but there was no time for that. My role was being an arranger and bandleader and that’s what people asked me to do. Now I have the time to write compositions, but the inspiration is no longer there. It’s too late, I guess!”

“I still like to meet the musicians with whom I worked and who are still alive – although their number is decreasing rapidly, of course. Whenever I meet one, I’m always surprised when he says, ‘Do you remember that one concert we did fifty years ago?’, or something along that line. Usually, I don’t remember instantly, because I did so many different things. Then the memory slowly comes back and it makes me very happy. There are so many great things to look back on. I have the good fortune of still being in good health. Whereas I was a social guy all my life, I’m now happy to take it easy and live quietly. Perhaps that’s the secret of a long life; don’t get involved too much… and keep listening to good music, that’s the best advice I can give to anyone!”

EUROVISION SONG CONTEST

Lars Samuelson took part as a conductor in three Eurovision Song Contest editions, the first one being in 1969, when he was a fledgling 33-year-old record arranger. In that year’s Swedish preselection, Melodifestivalen, he had two irons in the fire, ‘Judy, min vän’, performed by Tommy Körberg, and ‘L, som i älskär dig’ by Britt Bergström, for both of which he got to conduct the orchestra for his own arrangement. Whereas Bergström failed to make an impression and finished in joint-last place, Tommy Körberg won the competition and thus became Sweden’s representative at the international festival in Madrid. As such, Samuelson got to join him as Sweden’s musical director at the contest in the Spanish capital.

“It wasn’t the first time I’d worked with Tommy,” Lars Samuelson recalls. “I had already done an album with him and he was popular; one of a young generation of singers making their mark. His songs were receiving a lot of airplay and Tommy himself was invited to perform in television shows regularly. To me, that explains in part why Tommy won Melodifestivalen. It was the first time he took part and the audience were looking for a fresh face. He was young, good-looking, and of course he had a very good voice. As a composition, ‘Judy min vän’ wasn’t anything special; just a normal song, but it worked because it had a little pop rhythm which gave it a more modern sound than the average Swedish popular song in those days. That was the other key to the success.”

“It was the first time I took part in Melodifestivalen as a conductor, but I had been involved previously. On one occasion, three or four years earlier, I had been in the trumpet section of the orchestra accompanying the programme. I was happy to take part in Melodifestivalen as a conductor. At the time, it was a good music programme in which the artist and the song were the central features. Going to Spain was an exciting prospect. I had been abroad before, performing as a trumpet player in bands and orchestras on tour in Denmark and West Germany, but this was something of a different level. The Eurovision Song Contest in Madrid was the first time I was part of a real international event – or the international music world, if you like. I was quite nervous being a part of that, although I knew what I was supposed to do – but when you’ve never been to such a festival, you don’t really know what to expect.”

Tommy Körberg (far left) during the studio recording of 'Judy, min vän' with (from left) producer Gunnar Bergström, songwriter Roger Wallis, and engineer Michael B. Tretow

“Before we left for Madrid, there had been some discussion in Sweden about Spain hosting the contest. There were some people who argued that we shouldn’t be going there in the first place, because this was a dictatorship led by a fascist, Franco. It was a political discussion. I didn’t get involved in that. My view has always been that politics is the business of politicians and music the business of musicians. I was in it for the music. Music is the one language in the world that I believe in. With my music, I can play anywhere in the world and reach out to others. If some other people say that I shouldn’t do this or that, I won’t listen, because they don’t know a thing about music. I’ve performed just about everywhere… Lebanon, India, Romania, Bulgaria, and I never gave any thought to the political situation in those countries. Maybe it was bad thinking, I don’t know, but to me the music was all that mattered. We went to Madrid and just did our performance the way we were supposed to do without having any business with Mr Franco.”

“Of course, we noticed that the security was strict. You could walk about in Madrid as a tourist freely, but around the concert hall there were hordes of policemen – and they took their job very seriously. One day, they even refused to let me in for rehearsal, because I had forgotten to take my accreditation pass with me. They only let me in after I had shown them my name in the programme booklet. It didn’t make me nervous. As I explained, I was there purely to do my job as a musician. I was a little nervous about conducting the orchestra, but the other circumstances didn’t concern me much.”

“The thing I was most afraid of when stepping onto that conductor’s platform in Madrid for the first rehearsal was the language barrier. Around me, I was hearing only Spanish, a language that I don’t understand. I had been hoping to get by with a little English. At that point, one of the violinists stood up and started speaking in Swedish to me! It was something I hadn’t expected. He said, ‘I worked in Sweden, so I can help you translating your instructions for my colleagues.’ That was a relief.”

The lapel pin reading 'actuante' (Spanish for 'performer') serving as an accreditation which Lars Samuelson forgot to put on his jacket - as a result of which he nearly missed a rehearsal in Madrid

“As far as I remember, after that, the rehearsals were easy. I’m aware that I’m not a good conductor, but you didn’t have to have a good technique to conduct a Eurovision song. You just started the band and then the tempo remained the same until the end. The main thing was checking in rehearsal if all the musicians played their parts correctly. If a section of the orchestra came in at the wrong moment, it was up to the conductor to tell them and give them a clear cue to make sure that they would fall in at the right time. Once that job had been done in rehearsal, you just started the band and beat the same tempo for three minutes. There was nothing more to it.”

“During rehearsals, I met the conductor who took part for Britain, Johnny Harris. He was a character! I knew that he was a seasoned arranger and conductor for lots of BBC television shows and I was looking up to him immensely. Here was a musician who had seen it all before and who seemed to know exactly what he was doing. I was new to all this, so I was in awe of this man.”

“In between rehearsals, we had a good time with Tommy and the Swedish TV production team which had joined us in Madrid. We were also happy to meet Siw Malmkvist. She took part for Germany. I worked with her a lot, even accompanying her to Munich, where she had been booked to perform with my band in a nightclub for half a month. During our time in Germany, we also did some TV gigs with Siw. She was really popular in Germany at the time. It was fun to meet her in a completely different country. We didn’t care about her being our rival. We were friends and we had a great time together. Tommy was much younger and less experienced as an artist than Siw, but I don’t remember him being very nervous. I had the impression that he was happy to be there.”

Tommy Körberg and Siw Malmkvist posing for press photographers in a bullring in Madrid in between their rehearsals for the Eurovision Song Contest

“I didn’t expect us to win or do really well in the voting. There were a lot of good songs taking part. We weren’t among the best and not among the worst, so I suppose we just about deserved what we got (finishing ninth in a field of sixteen – BT). Looking back, Madrid was a good experience. You were there a whole week, performing a three-minute song four or five times in rehearsal – and then one more time in the concert. Doing that first contest changed my career. It was my breakthrough on Swedish television. Television producers started taking notice of me and invited me to be the musical director for many different shows in the following years. Until that time, I had done a lot of radio, but TV was a new line of work for me.”

Three years later, in 1972, Lars Samuelson was also commissioned to take on the role as musical director of Melodifestivalen, the Swedish Eurovision selection programme. Eventually, Samuelson took on this role four times; after 1972, he was asked again in 1973, 1974, and 1977. Apart from having to bring together the orchestra, he conducted the entries for participants who came without a conductor of their own choice.

“These could also be artists who competed with a song which I had arranged myself,” Samuelson adds. “In those years, I was record arranger for singers like Tomas Ledin, Titti Sjöblom, and Lasse Berghagen. For their festival entries, I naturally conducted the orchestra myself. The orchestra for the national final wasn’t the Swedish Radio Big Band, although I asked some musicians from that band – but most of the players were the guys I worked with in the recording studio. In order to play this type of pop music, you have to be able to learn scores fast. Jazz guys are trained to be good improvisers, but some of them tend not to be that fast reading scores. For such a programme, you don’t have that much time to rehearse a set of songs. Everything had to be done in a hurry. Musicians were always eager to be in the Melodifestivalen orchestra, because it was high-profile work and the pay was generous.”

Looking well-turned out and smart while walking onto the conductor's platform for the Swedish performance at the Eurovision Song Contest in Madrid

In 1973, after having led the orchestra for Melodifestivalen, Lars Samuelson travelled to Luxembourg with the Swedish delegation – not to conduct the orchestra, but to be one of the jurors in the international Eurovision final, held in the Grand Duchy’s capital. Between 1971 and 1973, the result of the contest was determined by a jury consisting of two people from all competing countries.

“Swedish television asked me to go there. They thought I was a logical choice, given that I had been the bandleader in the Swedish final. I felt obliged to do it, because I worked so extensively in broadcasting at the time. The other Swedish juror was Lena Andersson, a singer who was under contract with Stikkan Anderson’s company Polar. I was in Luxembourg for a whole week. We were staying in a hotel in a public park, closed off from the outside world. There were no other houses around it; it was a place which was completely isolated. The building was surrounded by soldiers guarding the place. This might have had to do with Israel taking part in the competition (after the Munich massacre at the 1972 Summer Olympics, authorities in Luxembourg were afraid of more Arab terrorism directed against Israelis – BT). You couldn’t go anywhere. As a juror, you were obliged to attend all rehearsals. I felt I was wasting my time, being stuck in a hotel and then being led out to the theatre to watch others at work. This was boring. I’m a musician and I prefer to play. I did the job to please Swedish television, but my heart wasn’t in it.”

Strikingly, Samuelson did not give any participating entry the maximum of five votes. He gave four votes to just two songs, ‘Tom Tom Tom’ by Marion Rung (Finland) and ‘Power To All Our Friends’ by Cliff Richard (UK). “I must admit that I don’t remember a single song taking part that year, so I cannot explain why I didn’t give five points to any of them – other than that I must have honestly felt that nobody was good enough to earn a maximum. The stand-out memory of my week in Luxembourg is that Swedish Radio refused to pay me the bill of the hotel bar. One night, I had offered a drink to the jurors from all the participating countries. When I filed the declaration, those in charge of the broadcaster in Stockholm said they couldn’t pay for those kinds of expenses. In all, I don’t have the happiest of memories of Luxembourg.”

Juror's accreditation for the festival in Luxembourg (1973)

The following year, in 1974, Melodifestivalen was won by ABBA, who then went on to help Sweden win their first Eurovision trophy with ‘Waterloo’. The song was conducted by Sven-Olof Walldoff. The year before, ABBA had also been in the Swedish final, but on that occasion their entry ‘Ring ring’ had failed to win the competition. Contrary to ‘Waterloo’, ‘Ring ring’ was conducted by Lars Samuelson.

“Yes, I conducted it, but I didn’t write the arrangement,” Samuelson comments. “I suspect Sven-Olof Walldoff wrote that score as well, but perhaps I had to take over from him as a conductor because he had other obligations. I honestly don’t remember. I do remember that Benny and Björn were looking up to me a little bit at that early stage of their career. They were part of a younger generation of pop musicians who had huge respect for the studio guys who were into jazz and had the theoretical knowledge of music they didn’t have. Don’t forget they were ten years younger than me. For them and guys like Tomas Ledin and Björn Skifs, I was a bit of a father figure. I didn’t feel it that way, but I guess some of them did.”

“I would lie if I told you I saw the potential of ABBA as an international band before they won the contest in 1974. They were a normal group and in the beginning their music wasn’t that good. For me, ‘Waterloo’ wasn’t a winner. I respected Björn and Benny; they were really nice guys, but I was surprised when they won the Swedish final. If you ask me, the key to their success was their manager, Stikkan Anderson. He could sell anything. He opened the door for them, taking them under his wing and allowing Björn and Benny to relax and focus on the musical side. Stikkan had a great talent for marketing and he sold the group to a worldwide audience in a way nobody else could have done.”

With ABBA's Benny Andersson (photo probably taken at Melodifestivalen 1973)

“Of course, making Sven-Olof Walldoff dress up as Napoleon was Stikkan’s idea as well. It was a typical gimmick which only he could come up with. I can tell you that I was happy that I wasn’t in Sven-Olof’s place. I wouldn’t have done it, that’s for sure. It was a bad idea. Most people thought it was funny, but that was all it was. It didn’t help the song at all. Walldoff was a very nice guy. We were friends. He was originally a trumpet player like me – and also like me, his main quality as a record arranger was that he was very fast. He worked as a studio arranger for many years and that remained his main field of activity. He did some TV work, but not that much.”

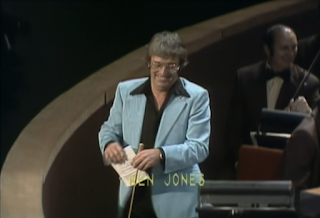

In fact, one of those TV assignments for Walldoff came along in 1975, when he took over as musical director for one edition of Melodifestivalen, held in Gothenburg. In that programme, Lars Samuelson took part as conductor of three entries, including the winning ‘Jennie, Jennie’, composed and performed by Lars Berghagen.

“They used to say that the guy who came second in Melodifestivalen in one year, usually wins the year after, and that’s what happened with Lars Berghagen,” Lars Samuelson thinks. “He had been defeated by ABBA the year before and so I guess it was his time. He was popular with the Swedish audience and, in that respect, you could say he deserved the win. Not that I was expecting it – I’m surprised every year with who wins Melodifestivalen. Even after all those years, I can’t tell you why one song catches on and the other doesn’t. The general public and I don’t have the same taste. ‘Jennie, Jennie’ was a typical song for Lars Berghagen. He was a Schlager singer. It’s no coincidence he also recorded it in German. Lasse was attempting to break into the German market in those years. The song was easy to arrange; very straightforward, nothing special really.”

Lars Berghagen celebrating his first place in Melodifestivalen 1975 in Gothenburg

“At that time, I worked extensively with Lars Berghagen. I arranged three or four albums for him and we also did several summer tours across Sweden. He usually accompanied himself on the guitar while singing. Yeah, he was a good guy and pleasant to work with, although I wasn’t that close to him personally. Our relationship was purely professional – two professional musicians doing their job together.”

“Originally, Swedish television had asked me to do the MD job,” Samuelson reveals, “but the string players didn’t think I was classical enough to conduct them. Contrary to the freelance orchestras which usually accompanied the Swedish finals, the majority of the players in that Eurovision orchestra came from the SR Symphony Orchestra. They weren’t necessarily the best musicians to accompany pop songs. When they had made it known they didn’t want to work with me, the producers turned to Mats Olsson. I wasn’t angry about that at all. Mats was a fine musician and an excellent arranger. He was a little older than me. When I started my career as a studio musician, I had been his copyist for some time. I was on good terms with him. It was a sound idea to ask him for the Eurovision job in Stockholm. Mats had to attend the rehearsals of all the participating countries. Perhaps he was a little more patient than me; I would have found that very tedious. The only thing he got to do in the live show was conduct the introduction and some interval music. I was happy to just have to do the Swedish song.”

Lars Berghagen on the Eurovision stage in Stockholm, backed up by The Dolls (Annica Risberg, Kerstin Dahl, and Kerstin Bagge)

In the run-up to the international final, a group of Swedish artists who felt the Eurovision Song Contest was too commercial organised an alternative festival by way of protest. Strikingly, their ringleader was Roger Wallis, who had been the composer of Tommy Körberg’s ‘Judy, min vän’ six years previously.

“They were crazy,” Samuelson laughs. “They called their own work progressive music, but there was nothing progressive about it. It was the same type of pop music that everybody was singing at the time. They claimed Eurovision was too commercial, but in the end all pop music is about reaching an audience, isn’t it? In fact, other than that, I don’t remember much of the contest in Stockholm. I wasn’t away in a foreign country, I wasn’t staying in a hotel. For the rehearsals, I drove down to the hall from my own house – and straight back after they were done. I was busy working on other arrangements, and I could use all the time that was available. On the night of the concert, I just conducted Lars Berghagen’s song and then I went home again. I didn’t wait for the voting, because we weren’t expecting Lasse to win – at least, I wasn’t. I guess I wasn’t feeling so involved that year.”

In the end, ‘Jennie, Jennie’ finished in a respectable eighth place. After Sweden skipped the 1976 Eurovision Song Contest, the country returned in 1977. For that year’s national final, Lars Samuelson was back as musical director, conducting three of the ten competing entries himself. The winning song, ‘Beatles’ by the group Forbes, was arranged and produced by Anders Berglund. Berglund was the pianist in Samuelson’s orchestra that night, but stepped up to the podium to conduct this one entry, which incidentally also was his conducting debut in the contest. In the Eurovision final in London, ‘Beatles’ failed to catch on with the jurors, finishing in last place.

Being introduced as musical director of Melodifestivalen 1977

“This was one of the few occasions where I can say that I saw the bad result coming,” Samuelson comments. “‘Beatles’ was a weak song. It was a bad idea to sing a song about The Beatles to begin with. You don’t write a song about them – they’re too big for that. Another thing was that the song itself didn’t resemble the style of The Beatles at all. It sounded more like a parody. I guess the result wasn’t that much of a disaster for Anders Berglund. He had the opportunity to prove himself as a conductor like I had done in Madrid. It was a big thing for him at the time.”

Kickstarting his television career, Anders Berglund was invited to take over from Lars Samuelson as musical director for Melodifestivalen 1978. “Some of the musicians I usually worked with were angry with the decision to have me replaced with Anders,” Samuelson recalls. “It wasn’t that they didn’t like him – not at all, but they simply couldn’t understand what I had done wrong. I knew what the reason behind it was. For the 1977 Swedish final, I had skipped three hours of rehearsals. Those rehearsals started on Monday, but I had had a concert with Sammy Davis Junior in Oslo on Saturday, and another one in Copenhagen on Sunday. We then took the night train to Stockholm. On Monday morning, although feeling utterly exhausted, I did the first full day of rehearsals for Melodifestivalen. That same evening, we flew over to Helsinki for another show with Sammy Davis.”

“Coming back from Finland the day after, I was so tired that I decided to take a couple of hours of extra sleep. I knew that the morning session with the orchestra was going to be spent on songs which weren’t going to be conducted by me anyway. There were other guys conducting the band. I arrived at 1pm to do the afternoon session. In that morning rehearsal, I would have had nothing to do, except being there to oversee what others were doing. Some people in the production team weren’t happy about that. They felt I had been lazy. One of them was the main producer of Melodifestivalen the following year – and he decided to ask Anders instead of me. The way the decision had come about was strange, but this wasn’t a disaster. I think it was time to have someone new take over the Eurovision job, a younger guy. Anders put a lot of energy into the show and he did a good job on it.”

Ted Gärdestad (left) with session guitarist Janne Schaffer during the recording of the former's debut album 'Undringar', produced by ABBA's Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus (1972)

Other than that, Anders Berglund also added a string section to the Melodifestivalen orchestra. For the last three of the four festival orchestras put together by Lars Samuelson between 1972 and 1977, there had just been an extended big band without string players. “Mind you, I would have liked to have strings in my festival orchestras as well, but I wasn’t given the budget to do so,” Samuelson points out. “Apparently, more money had been set aside for the 1978 final. It could be a bit of a challenge to accompany pop songs with just a big band. You had flutes and an organ to cover it up a bit, but for some songs strings would have made for a better sound.”

After giving up the MD’ship of Melodifestivalen, Lars Samuelson returned in the following years as conductor of two more entries, the disco-esque ‘Harlequin’ by the eponymous group in 1978 and ‘Satellit’ by Ted Gärdestad, which won the competition in 1979.

“I had been involved with Ted Gärdestad practically from the start, writing some of the arrangements for his early albums. He was very young at the time. In those early years of his career, Björn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson took care of Ted. When they no longer had the time to work with him after the breakthrough of ABBA, Janne Schaffer took over as his producer. Janne is an excellent guitarist who performed with Stan Getz at the Montreux Jazz Festival. I’ve always been close with Janne. It’s something you can’t explain; with some people, you feel a connection, and with others you never will. Janne and I have always had this connection. I was the producer of his first solo album and I called upon him to play in all my sessions. He was also a permanent fixture in my television orchestras and the SR Big Band.”

“Janne was a very able arranger for Ted. He was well versed in contemporary pop music, much more so than I was in 1979. By that time, I had practically given up working as a studio arranger for pop songs. When Ted was chosen to perform ‘Satellit’ in Melodifestivalen, Janne Schaffer called upon my help. In the recording studio, he usually wrote Ted’s arrangements, but his way of arranging wasn’t with pencil and paper. Instead, he used to do it by playing the guitar and telling the other guys in the studio how he wanted them to play their parts. These were band arrangements without strings or brass – and they were very good ones, because Janne has always had a good ear. However, he never conducted, not even in the studio; this was something that suited me better. That’s why Janne asked me to add strings and brass parts to this one song, ‘Satellit’, and conduct it in Melodifestivalen. So the arrangement was a combined effort of the both of us.”

Ted Gärdestad in the early years of his career with his manager Stikkan Anderson

“I wasn’t surprised when Ted won the Swedish final. At the time, he was a very popular artist in Sweden and this was a good song. The lyrics are very good, which you don’t find very often in a Eurovision song. Ted’s brother Kenneth wrote them; he usually wrote the lyrics for Ted’s songs. The music was also interesting. It had an American pop rhythm in it, which gave the song a modern feel. It was a big hit in Sweden and it has become some sort of an evergreen.”

After winning Melodifestivalen, Ted Gärdestad represented Sweden at the 1979 Eurovision Song Contest final, held in Israel’s capital Jerusalem. On the official participants’ list compiled by Israeli television, the page detailing the members of the Swedish delegation mentions Lars Samuelson as conductor and Janne Schaffer as his assistant conductor, a somewhat unusual description. “Of course Janne didn’t help me with the conducting job,” Samuelson explains, “but he had co-written the arrangement with me, so probably that’s why Swedish television gave him that title when sending the list of names to Israel. Janne didn’t have a role other than being with us in Jerusalem and sitting in at the rehearsals. Apart from that, we were simply together as friends, enjoying each other’s company.”

“After that first Eurovision ten years before in Madrid, I had been abroad a lot and I really liked to travel, but I had never been to Israel before. It turned out to be a very nice trip. I had my wife with me. Together, we visited the Wailing Wall in the old town of Jerusalem – and with the Swedish delegation, we went on a daytrip to Masada and the Dead Sea. I can still see myself floating on the salty water while pretending to read an Israeli newspaper. Yeah, it was a good experience. The local people organising the festival took good care of you. The security measures were quite strict, with armed soldiers on every floor of the hotel in Jerusalem we were staying in, but I suppose they were necessary.”

Ted Gärdestad with Janne Schaffer, who had meanwhile taken over as Ted's producer from Björn and Benny, at work on the studio version of the 1979 Swedish Eurovision entry 'Satellit'

“At the first rehearsal with the orchestra in Jerusalem, the exact same thing happened to me as in Madrid ten years before. Most of the musicians spoke only Hebrew, but one of the players in the string section stood up and said that he had worked in Sweden in the past – and that he was happy to be my translator. I was happy with the way the orchestra performed, but Ted and Janne weren’t really. They were complaining that the rhythm section sounded a bit old-fashioned, without the oomph they were looking for. Remember that ‘Satellit’ was quite a modern song. Ted especially felt he had to work with orchestra musicians who didn’t understand his type of pop music. That’s what he told us, but he didn’t feel like talking to them about it.”

“I explained to Ted and Janne that we just had a couple of short rehearsals. There was just time to look at the broader picture – making sure that the musicians were playing the right notes, which they were. In such a situation, you can’t go into detail, having long conversations with the guys in the rhythm group. They had so many other songs to rehearse as well. You see, Ted was a young guy with another feeling for music – and he was a good musician; in Jerusalem, he played the electric piano live on stage. After I had talked to him, he understood the situation and that was the end of the discussion. None of our delegation complained with the Israeli production team and rightly so. The orchestra was just fine.”

“In Jerusalem, I was happy to meet some musician friends. The first was Allan Botschinsky, an excellent trumpet player who conducted the Danish entry. The first time I had met him was when the Swedish Radio Jazz Group travelled to Copenhagen to do a programme together with the Danish Radio Big Band, of which Allan was a member. Later on, I worked with him in Helsinki for an album by Esko Linnavalli which I produced (‘A Good Time Was Had By All’ in 1976 – BT). It was a big band recording. For those sessions, a real star ensemble of jazz instrumentalists came to Finland. These included Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, Dexter Gordon, and Allan. Allan was a bit withdrawn and I doubt if he enjoyed taking part in Eurovision all that much. In Jerusalem, we spent some time together and had a drink.”

The winning team of Melodifestivalen 1979 enjoying the afterparty, from left - producer Janne Schaffer, Ted's brother and lyricist Kenneth Gärdestad, Ted himself, and conductor Lars Samuelson

“Another guy who I knew in Jerusalem was Fritz Pauer. He played the piano on stage for the Austrian entry. One year before, he had been part of a quartet of musicians featuring on an album with Rolf Ericson and Johnny Griffin produced by me (‘Sincerely Ours’ – BT). Those sessions had been done in a studio in West Berlin, which was virtually next to the Berlin Wall. Fritz was an excellent jazz pianist. It was a nice surprise to meet him at the Eurovision Song Contest.”

In the voting procedure, ‘Satellit’ never got away from the lower regions of the scoreboard, eventually having to settle for seventeenth place in a field of nineteen entries. The Swedish delegation must have had higher hopes, but Samuelson shrugs his shoulders.

“We didn’t feel too disappointed… at least I didn’t. This is a game and everybody comes up with a completely different song. It’s hard to judge music anyway. Ted wasn’t too down-hearted about it. I don’t think he was ever thinking seriously that he could win the festival. Ted, his brother Kenneth, Janne – they were all philosophical about the result. The only guy who was deeply unhappy was Stikkan Anderson, who had come to Jerusalem as Ted’s manager. After he had propelled ABBA to world fame, he was living in parallel universe high up in the sky. He thought he could sell anything to anyone worldwide. We would all have been happy with a few more points for Ted, but Stikkan was in it to win the whole thing. His expectations were unrealistic.”

Ted Gärdestad celebrating his Melodifestivalen victory on stage

“My most lively memories of Israel are of our journey back home. The delegations from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden had all been booked on the same flight to Copenhagen. Initially, we were told we had to wait because the weight of the baggage was too high. Then it turned out security officers were checking everyone’s luggage. Apparently, there was a bomb scare. This took two-and-a-half hours. Then the all-clear sign was given; there was no bomb after all and we could take off. On the flight, we had one big party with all three delegations, celebrating that we were on a plane which was bomb-free!”

Coming back to Sweden, Lars Samuelson wrote the arrangements to two single records with Swedish-language cover versions of songs taking part in the contest in Jerusalem; ‘Colorado’, the Dutch entry, with Lill Babs; and ‘Hallelujah’, the Israeli entry, with Jan Malmsjö – with versions of the songs from Spain and the United Kingdom on the B side. “Honestly speaking, I have only vague memories of that,” Samuelson comments. “I remember a producer asked me to work with Jan Malmsjö to record the winning song, but nothing other than that. With over 4,000 arrangements written, many of them went into the black hole of my brain! It was just another job.”

“It was the last time I worked with Ted. The bad result in Eurovision certainly wasn’t the end of his career in Sweden. He was popular for some more years, but then he became religious and got into Bhagwan. Until that time, Janne Schaffer had guided him artistically, but unfortunately Ted lost the plot on a personal level. It’s very sad how his life ended at such a young age. He was a really nice guy.”

Gärdestad seated at his electric piano during one of the Eurovision rehearsals in Jerusalem

In 2000, 21 years after his last participation as a conductor in the Eurovision Song Contest in Jerusalem, an unexpected epilogue followed in Lars Samuelson’s Eurovision career. His record company Four Leaf Clover released the Swedish festival entry ‘När vindarna viskar mitt namn / When Spirits Are Calling My Name’, performed by Roger Pontare. In the international final, held on home soil in Stockholm’s Globe Arena, this Swedish effort finished in seventh place.

When asked how this song crossed his path, Samuelson explains, “It was offered to me by Roger’s publisher. He was looking for a record company and I decided to do it. In fact, Roger had been in the Swedish final the year before – and then I had agreed to release the song as well, but that one didn’t win. Four Leaf Clover was always a company which mainly released jazz music and not so much pop, but Roger is a unique singer with a very strong voice. A couple of years earlier, he had released an excellent jazz album with Sinatra songs. I had worked with him as an arranger and I liked him. When first hearing a demo of Roger’s Melodifestivalen song in 2000, I didn’t have to think twice. I wasn’t surprised when it won the Swedish final. It was the strongest entry that year – an unusual song with a folk element woven into it and meaningful lyrics.”

“Roger wasn’t your typical Eurovision singer, but he liked to do the festival. He had taken part before with a duet partner (representing Sweden at the contest in Dublin in 1994 with Marie Bergman and the song ‘Stjärnorna’ – BT). In a country like Sweden, where the contest is popular, it’s a good move for any artist to try his luck in Melodifestivalen. After the festival, you can go on a summer tour and do lots of concerts. There’s no artist who says no to such a prospect.”

“I just produced the song; I wasn’t involved in writing the orchestration. That was done by Peter Ljung. Peter was the pianist in Curt-Eric Holmquist’s orchestra which accompanied Melodifestivalen in Gothenburg that year. I asked him to rewrite the record arrangement for the orchestra – which was the best idea anyway, because he was there in rehearsal and could discuss the score with Curt-Eric and the other musicians in the band. Unfortunately, there no longer was an orchestra to accompany the international final. I was there in Stockholm, but just in rehearsals. By the time the show got underway, I was happy to be back home sitting in front of my television. Apart from Roger, I liked the Olsen Brothers. I had already noticed them during rehearsals and I was happy when they won the contest for Denmark. They were very nice guys. Later on, I wrote them some arrangements when they came over to Sweden to do a one-off concert with the Malmö Fire Brigade Orchestra.”

Inducted in the Melodifestivalen Hall of Fame (2020)

“Around the same time that Roger Pontare took part in Eurovision, Swedish newspapers were writing how much better it was now that there was no orchestra sitting on stage and spoiling the image. I can’t begin to understand such a view. To me, a contest with just backing tracks and without an orchestra is like a Christmas tree without decorations on it. Since they had the orchestra removed from the programme, the music no longer seems to be the focal point. Don’t get me wrong, I have nothing against dancers – dancing can be wonderful to watch, but the festival used to be about melodies. Nobody seems to care about the melodies anymore. The image is all that counts.”

“I do still tune in for Eurovision, because whether you like it or not, it’s still an important event… but I can’t bear to watch it from the start. I prefer to switch on the television when they show the short versions of all the songs just before the voting. I do wish they would rethink the formula. It would be so much better with an orchestra. Hearing and seeing real musicians playing the music would make the songs much more interesting to listen to. Looking back, it’s ABBA who started it. They were the first to use pre-recorded backgrounds for their song in Sweden – and they spoiled the whole thing.”

“In 2020, I received an award and I was inducted into Melodifestivalen’s Hall of Fame. It was nice to be reminded of my involvement in Eurovision, but I wouldn’t say that it was a stand-out experience in my career. I mean, I worked on so many other TV shows. In I morron e’ de’ lörda’, a music programme with the SR Big Band in the 1970s, I got to work with international stars who were flown in from England and the States. I have sharper recollections of that show. But regardless of that, Melodifestivalen and Eurovision were and still are important events. At my age, you have so much to look back on and you have to be proud of everything you did. Of course conducting the festival was just a job, but it’s always nice to hear when other people recall your work from the past.”

OTHER ARTISTS ABOUT LARS SAMUELSON

Singer Titti Sjöblom recorded her first three albums with Lars Samuelson as her arranger in the early 1970s: “When I accepted the offer to make my first solo album, my terms were to be allowed to pick the songs and the musicians myself. I insisted on having Lars Samuelson and his big band. His arrangements sounded a bit like Blood, Sweat & Tears; very modern. The musicians in his band were the best available in Sweden. Lasse himself was fantastic to work with. He was always cool and calm, making everyone around him feel at ease and give their very best. I also noticed how his musicians appreciated working with him. He was right when he said that he was satisfied with the arrangements for my first album in 1972, because they were excellent. Later on, Lasse came up with the idea to ask Per-Erik Hallin to write a song for me. Per-Erik was the favourite piano player of Elvis Presley and worked in Las Vegas for some years. It was the beginning of a happy artistic partnership between Per-Erik and me; we performed a lot together in Sweden and beyond. I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to work with Lasse for so many years. I also was good friends with his charming wife Jeanette and their son Håkan. (2024)

With Titti Sjöblom (1971)

EUROVISION INVOLVEMENT YEAR BY YEAR

Country – Sweden

Song title – “Judy, min vän”

Rendition – Tommy Körberg

Lyrics – Britt Lindeborg

Composition – Roger Wallis

Studio arrangement – Lars Samuelson

Live orchestration – Lars Samuelson

Conductor – Lars Samuelson

Score – 9th place (8 votes)

Country – Sweden

Song title – “Jennie, Jennie”

Rendition – Lars Berghagen

Lyrics – Lars Berghagen

Composition – Lars Berghagen

Studio arrangement – Lars Samuelson

Live orchestration – Lars Samuelson

Conductor – Lars Samuelson

Score – 8th place (72 votes)

Country – Sweden

Song title – “Satellit”

Rendition – Ted Gärdestad

Lyrics – Kenneth Gärdestad

Composition – Ted Gärdestad

Studio arrangement – Janne Schaffer / Lars Samuelson

Live orchestration – Lars Samuelson

Conductor – Lars Samuelson

Score – 17th place (8 votes)