The following article is an overview of the career of Spanish singer-songwriter, arranger, and producer Ramón Arcusa. The quotes are a mix of two sources; first, there are Ramón Arcusa’s entertaining and very well-written memoirs: 'Soy un truhan, soy un señor’ (ed. MR: Barcelona, 2020). Additionally, Bas Tukker had an extensive email exchange with Mr Arcusa in July and August 2020, discussing various parts and aspects of the latter’s career in music. The article below is subdivided into two main parts; a general career overview (part 3) and a part dedicated to Ramón Arcusa's Eurovision involvement (part 4).

All material below: © Bas Tukker & Ramón Arcusa / 2020

Contents

- Passport

- Short Eurovision record

- Biography

- Eurovision Song Contest

- Other artists about Ramón Arcusa

- Eurovision involvement year by year

- Sources & links

PASSPORT

Born: December 10th, 1936, Barcelona (Spain)

Nationality: Spanish

Nationality: Spanish

SHORT EUROVISION RECORD

As a songwriter, Ramón Arcusa represented Spain in the Eurovision Song Contest on three occasions. In 1968, teaming up with Manuel de la Calva, he composed the Iberian country’s first winning entry, ‘La, la, la’, performed by Massiel. Four years later, Arcusa was invited by composer Augusto Algueró to write the lyrics to ‘Amanece’ for Jaime Morey. Finally, in 1978, he co-signed and arranged ‘Bailemos un vals’, with which José Vélez obtained a ninth place in that year’s festival final in Paris; for this last entry, Arcusa conducted the Eurovision orchestra himself.

BIOGRAPHY

Born in the grim years of the Spanish Civil War, Ramón Arcusa Alcón grew up in an Aragonese family which had moved to Barcelona. His father earned a living as a metal worker. Due to meagre living conditions in Barcelona itself, Ramón spent part of his childhood at his mother’s family in the Teruel region. As he relates in his memoirs, published in 2020 under the title ‘Soy un truhan, soy un señor’, he learnt to sing traditional Aragonese jotas at an early age.

“Many Sunday afternoons, we met up with other families hailing from Aragon, each week in a different house. The atmosphere used to be wonderful; there were cookies, pasta, wine, or some cheap liquor made with powders of concentrate and alcohol, and people used to sing jotas, tell tales, and exchange gossip. Each brought what he could to liven up the party. My father played the guitar as well as the bandurria, the Spanish mandolin, and was great at singing jotas. My brother Alfredo and I used to sing the tunes he had taught us, while accompanying ourselves at the guitar. Actually, we enjoyed quite some success! We even won singing contests organised at the Centro Aragonés, where the Aragonese community of Barcelona used to meet. Besides, I also sang in the church choir of my primary school, in which I was given solo parts. Later, I became the leader of a children’s choir which I conducted in my own way. The role was given to me as I was the only boy able to read the score. Music was my hobby… I loved it!”

Noting his son’s talent, Ramón’s father entered him at the Barcelona Municipal Conservatoire of Music. “I was nine years old then,” Ramón adds. “My father thought I could make a career as a musician… how wrong he was, eh! I followed courses in solfege and piano. In theory lessons, I was always the fastest pupil when our teacher gave us the assignment to write down the melody that he was playing at the piano, but, on the downside, I was unable to sight-read music scores with the speed of a true musician. To make up for that, I learnt my piano scores by heart, which enabled me to pass the exams of both courses without too much of a problem. My father had bought me a second-hand upright piano. In our apartment, I spent a minimum of a couple of hours per day having a go at it. No doubt, the other residents in the building block – and those living in the surrounding blocks as well – must have hated me. I went to conservatory for just three years. It’s the only formal music training I received in my life. In retrospect, those courses in solfege and piano helped me more than I was prepared to believe at that time.”

When Ramón was twelve years of age, his parents decided to send their son to a vocational school, cutting short his regular education as well as his conservatoire lessons. Two years later, he was hired as an apprentice at Elizalde S.A., a manufacturer of aviation engines. Until 1958, he worked for the Elizalde mill as a technical draughtsman. There, he met his future singing partner in the Dúo Dinámico, Manuel de la Calva. Manolo was a young man of the same age, who had some experience as a jazz singer at Club Hondo in downtown Barcelona. Manuel and Ramón worked at the same department.

“The draughtsmen’s room, with drawing tables and matching drafting machines, was about eight by fifteen metres. From where I was sat, Manolo’s table was at the far end of the room. Sometimes, he was humming melodies which I, in my turn, would accompany with percussion rhythms, which I produced by hitting my table ‘artistically’ from a distance, while also adding voices ad lib in an attempt to imitate an orchestra."

"After some time, we found out we both were really ‘into’ music. One day, when we had been working in the same section for some three years already, I suggested to try and sing something together. I was curious if it would work. It must have been in the locker room of the factory, where I took advantage of an ‘oversight’ (which is the word we used for disappearing from the workplace for a while without permission) to take my guitar. There, we sang together for the first time. From the outset, we both saw that something interesting could come out of this. Of course, we didn’t find the right style immediately, but with just two voices and a guitar we already managed to create a pleasant sound. Manolo with his bright, distinct, very recognisable voice, and me trying to harmonise second voices behind, which were as interesting as possible. We were getting there! That’s how it all began: the Dúo Dinámico.”

Prior to teaming up with Manuel de la Calva, Ramón was part of Trío Calamidades, an amateur group which he formed with his brother Alfredo and a mutual friend, Emilio Tito; sadly, Alfredo Arcusa died unexpectedly after contracting peritonitis at the age of 25. Looking for a new opportunity to play music and carve out a musician’s career for himself, Ramón convinced Manuel to form a duo. As both guys were interested in new styles of music from England and America, they aimed at creating a rock ‘n’ roll repertoire in English… and by the end of 1958, the Dúo Dinámico made their stage debut at a winter festival on Barcelona’s Plaça del Sol. There, the announcer, unable to pronounce the English language, introduced them as Dúo Dinámico instead of the name they had come up with themselves: The Dynamic Boys. In the following months, they performed in local restaurants and cabarets while still retaining their daytime job at the factory. Meanwhile, Ramón bought his first electric guitar.

“There are no schools and universities for pop singers,” he comments. “Therefore, you must try by yourself, learning things here and there, copying, rehearsing, and of course – as with nearly everything in life – using your common sense, which is exactly what we did. At the Hondo Jazz Club, we obtained the most recent records from abroad, brought to us by an Air France steward, ranging from Elvis to Sinatra, but also Fats Domino, the Platters, Nat ‘King’ Cole, Paul Anka, and the duo which we idolised above all others: the Everly Brothers. They had a unique talent for creating a wonderful two-part sound. While we were rehearsing, we noticed we were getting our vocals right. What was more, they sounded different from those of other groups: we were identifiable, which was hugely important. In those early months, we also called ourselves The Du-du-á, because, when one of us sang the melody line, the other accompanied him by adding ‘dudua’ sounds. We were having fun.”

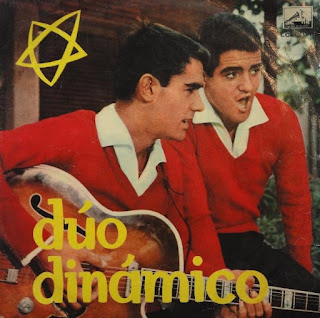

In 1959, the Dúo Dinámico were offered a record deal for four songs, to be released on an EP. Right from the start, Ramón and Manuel seemed to have a keen eye for marketing. “The general manager of the Odeón record company – the one with the wind-up disc gramophone and the puppy – was called Mr Alberich,” Ramón recalls. “Solemnly, he declared, “Of course, we don’t have the budget to put a colour photograph on the sleeve. It’ll be in black and white.” Manolo de la Calva and I were stunned. With the sleeve photo in mind, we had just bought bright red jerseys at Gonzalo Comella’s clothing store. Determinedly, we told him we would pay for the photo ourselves. We went looking for the best photographer, Jaime Déu Casas, who took the picture which was printed on the sleeve of our first EP. That photo put us back 1,000 pesetas, but it was cheap as we knew how important the image was. Those at the record company didn’t have a clue.”

Pioneers in the field of rock ‘n’ roll in Spain, the Dúo Dinámico touched the right cord at the right time. Their material, predominantly written by the boys themselves, thrilled teenage audiences, initially in Catalonia, and from their 1961 no. 1 hit ‘Quince años tiene mi amor’ onwards, in the rest of the country as well. Between 1959 and 1967, they released 36 EP records at Odeón, which sold an average of 100,000 copies. Other popular songs from those days include ‘Bailando el twist’, ‘Quisiera ser’, and ‘Amor de verano’. Over the years, the duo participated in various song festivals at home and abroad as songwriters and performers, winning the 1966 edition of the Mediterranean Song Festival in Barcelona with ‘Como ayer’ and representing Spain at the International Song Festival in Rio de Janeiro’s Maracanã Stadium that same year with ‘Un dia llegara’. Meanwhile, they toured Spain as well as performing for audiences in Argentina, Chile, Peru, Venezuela, and Mexico.

From the duo’s first Spanish tours in 1961 onwards, when they were still part of a variety show with other artists, Ramón, using the basic knowledge of music theory he had acquired in conservatory, wrote the scores for the accompanying musicians himself.

“At the outset, our song arrangements were just for a small rhythm group: drums, bass, electric guitar, and a piano – sometimes there was a vibraphone player or a saxophonist to play solos. Little by little, we became more adventurous, adding more instruments to the scores; our recordings became more sophisticated. In many places where we toured, there was an orchestra, which allowed us the possibility to experiment with small and bigger brass arrangements. Sometimes, we simply fell back on the arrangements which had been used in our recording sessions. Even there, I had a foot in the door from the very beginning. I used to make a written-down arrangement containing the basic elements: rhythm, string lines, brass, and choirs – and a Catalan arranger, Joan Bou, put all of it together. The conductor for most of our recordings was maestro Josep Casas Augé. Progressively, though, I took over more and more responsibility. From 1966 on, I wrote our arrangements entirely by myself.”

Ramón (left) and Manolo de la Calva (second from right) with composer and arranger Augusto Algueró and his wife Carmen Sevilla

In between touring and studio recordings, the Dúo Dinámico also found the time to record four films, including ‘Búsqueme a esa chica’ in which they featured alongside popular teenage actress Marisol. Towards the end of the 1960s, however, when music tastes developed in a different direction, public interest in the duo began to dwindle. Trying to recreate the success from earlier years, they signed deals with new record companies, first Vergara and later Parnaso – but to little avail. Their 1970 album, recorded in London with arranger Kenny Clayton and the best English session musicians, failed to catch on with Spanish audiences, who were only longing to hear their old hits… as Manolo and Ramón found out the hard way.

“‘Quince años’, ‘Quisiera ser’, or ‘Perdoname’… these were the songs they knew and wanted to hear. We looked at them, not without a certain amount of contempt and professional irritation, while we continued singing the repertoire we had recorded in England, determined to continue until the public discovered how good it was. Wrong, very wrong on our part! We learned a lesson. The moment wasn’t propitious for the music we were making either. These were the final years of the Franco dictatorship; half of Spain was craving for political change."

"At the same time, coincidentally, folk and protest songs became fashionable all over the world. Spanish political parties were no longer illegal by then. Lurking in the shadows, they didn’t miss the opportunity to take advantage of music styles which were fashionable to bring across their political message. Furthermore, it allowed them to gather their supporters in concerts without giving offence to Franco’s armed police. Suddenly, protest singers burst onto the scene, making their careers while political support and contracts lasted. It was then that journalists started asking us the one question which, due to the political climate, seemed to have become obligatory, “What message do you want to carry to your audiences?” We needed time to recover from this new type of interviewing, but, frankly, we simply didn’t have an answer ready. Or, perhaps, not the answer they wanted to hear.”

In 1972, after nearly fifteen years, Manuel de la Calva and Ramón Arcusa decided to withdraw from the stage. Although continuing to write song material together in the following years, they went their respective ways, signing deals as record producers for different Madrid-based companies, Manolo for Columbia and Ramón for EMI Odeón. Amongst other artists, Arcusa worked with Víctor & Diego, Paco Revuelta, and the folk band Vino Tinto. As a producer, he scored a number-one hit in 1974 with Manolo Otero’s ‘Todo el tiempo del mundo’, a cover of an instrumental by the Daniel Sentacruz Ensemble from Italy. Though he felt he initially lacked the theoretical background, Arcusa started writing arrangements for his protégés as well.

“This Manolo Otero song is a good example to illustrate my learning curve in those years,” Ramón explains. “The Italian version, called ‘Soleado’, had an arrangement which I thought was really good – and I decided simply to copy it from start to finish. Writing out the full parts for this song helped me learning much about arranging for bigger orchestral setups. Around the same time, I also bought myself the sheet music of classical works; Albinoni’s ‘Adagio’ is a title that springs to mind. Studying those scores was very instructive, as I found out about the range of each instrument. Of course, I had ample background to deal with choirs and vocal arrangements. All of this put together meant I could get by as an arranger. Fortunately, creating melodies and counter harmonies for any instrument has always been something which comes to me intuitively."

"After a while, I managed to create a personal style of arranging; something I liked doing, for example, was giving an electric guitar part to the string section. To me, writing arrangements is the best part of creating a song, building it on paper, instrument by instrument, and then, finally, listening to the result in the recording studio felt like an orgasm! Probably, it’s similar to what an architect experiences when he finally sees his designs being brought to reality when the building project is finished.”

In 1974, Arcusa left EMI, preferring the career of a freelance producer, which allowed him to work with artists of different record companies, including the likes of Ángela Carrasco, Braulio, and the disco formation Sirarcusa. In 1977, he arranged and produced two number-one hits, ‘Ella’ by Luis Fierro and his self-penned ‘Soy un truhan, soy un señor’ for Julio Iglesias. Subsequently, Iglesias succeeded in convincing Arcusa to also arrange and produce the following album ‘A mis 33 años’. Even though Ramón had only taken on the job on the condition that it would be a one-off affair, Iglesias was so happy with the result – artistically as well as commercially – that he implored Arcusa to work on his following recording projects as well. In the end, Ramón arranged and produced all of Julio Iglesias’ albums for the next twenty-odd years, whilst also composing or co-composing several of his greatest hits, including ‘Pobre diable / A vous les femmes’, Un día tú, un día yo’, and ‘Hey!’. In 1979, at the instigation of Iglesias – who had already abandoned Spain in favour of Florida –, Arcusa moved to Miami, where he has lived ever since. The LP ‘Hey!’ (1980) was the first of Iglesias’ albums (partly) recorded in America.

“Back in Miami, our real home became the Criteria Recording Studios,” Ramón recalls. “The first thing that surprised me when entering Criteria were the replicas of the hundreds of gold albums recorded there by all the greatest of greats in the music business. On the first day, we already met the Bee Gees, who had done their famous ‘Night Fever’ album there. Another artist we encountered was Gloria Estefan, the lead singer of the Miami Sound Machine. When the Bee Gees had finished their sessions, we settled down in Studio D, a small studio used for vocal recordings and sound mixing. If the Bee Gees had come out with ‘Night Fever’, why couldn’t we produce something worthwhile too? The rhythm track and orchestra recordings were still done in Madrid, but we spent months and months on vocals and mixes in Miami. The truth is that, at the beginning, the staff at Criteria, although always treating us with all due respect, thought of us as Martians: we were the crazy Spaniards coming to spend loads of money. They had no idea who Julio was…

Though, by then, Julio Iglesias was a star in many European and Latin American countries, he had his mind set on a breakthrough in the United States as well – not an easy assignment given his unwillingness to take English lessons. Finally, in 1984, he recorded an English album in Los Angeles, ‘1100 Bel Air Place’, co-produced by Arcusa with Richard Perry and with arrangements by, amongst others, Nicky Hopkins and Michel Colombier.

“Great artists participated as duet partners," Arcusa recalls, "most notably Willie Nelson in ‘To All the Girls I Loved Before’, which reached number five in the Billboard Hot 100 and number one in the country hit parade. It was a song composed in 1975 by Albert Hammond which had more or less passed unnoticed at that time. But Julio’s duet version with Willie made it sound fresh again. It was a worldwide success. The contrast between Julio’s natural elegance and the scruffy and bohemian sound of the country singer that was Willie Nelson was priceless. It was something which was off the beaten track… it was unexpected. Another important duet on that album was ‘All of You’ with Diana Ross, a magnificent performance by both artists, and the no less surprising collaboration with the Beach Boys in ‘The air that I breathe’. The suggestion to take care of the background vocals for this one song more or less came from the group themselves – imagine, suddenly we found ourselves working with this legendary group, including their alma mater Brian Wilson!”

While his partnership with Julio Iglesias absorbed much of Arcusa’s time and energy, he continued to work with other European artists as a producer and songwriter now and again, including Nino Bravo and Trigo Limpio, and, somewhat later, Paloma San Basilio and Christer Sjögren. Finally, in 1995, after eighteen years together, Julio Iglesias and Ramón Arcusa parted ways.

When asked about his own part in creating Iglesias’ worldwide success, Arcusa comments, “All those years, I worked with Julio, for Julio, but I never was his employee – because, formally speaking, I was hired by his record company who paid me for my troubles. This construction gave me much freedom. This meant that, with Julio, the conversation wouldn’t be about money, but about success stories we wanted to share with each other or about having found or composed a song that we considered suitable for his next album. Furthermore, with me, his recordings became more modern, more pop, and he dared to sing songs which, without the arrangements I made for him, he probably wouldn’t have accepted. Otherwise, I suspect he would have stayed in his comfort zone as a ballad singer."

"My scores for him were admired by Spanish musicians, but also elsewhere in Europe. My secret was always to think, in the first place, about the singer, and to avoid making his life impossible by leaving no space for his voice. In music, as in spoken word, sounds are as important as silences – and that was my belief. My inspiration came from Don Costa’s arrangements and the sound of Ray Conniff, whose musical concept I imitated. Finally, of course, the choirs were always very important in my arrangements.”

Ramón (to the right) with legendary Spanish composer Manuel Alejandro in Los Angeles on the occasion of the simultaneous release of two albums by Julio Iglesias: ‘Un hombre solo’, produced by Alejandro, and ‘Non Stop’, for which Ramón Arcusa shared the production credits with Tony Renis and Humberto Gatica (1987)

Meanwhile, in parallel with their activities as producers for other artists, Ramón Arcusa and Manuel de la Calva had taken up touring again as the Dúo Dinámico. In 1980, EMI released a compilation, ’20 éxitos de oro’, which sold more than one million copies. In 1986, they recorded a new album, enthralling audiences with fresh songs. Initially, the duo had been lukewarm about the idea of releasing new material.

When offered the possibility to record a new album in 1986, “it didn’t seem like a bad idea,” as Arcusa comments, “but we were haunted by our own fear of failing, of not living up to our own standards. Right, we had been singing in concerts for seven years again, but our last album, recorded in London in 1970, had not caught on at all, even if we were satisfied with it from an artistic perspective. Sixteen years without recording material is a very long time indeed for any artist – hence our doubts. Well, we accepted the challenge, but on one condition: if, after having recorded the album, we weren’t convinced about the result, we would burn the tape in the studio while downing a bottle of the best cava."

"In the end, we didn’t burn the tape, but we had our sparkling wine nonetheless, because the resulting album, with three medleys and six new songs, including ‘Tú vacilándome y yo esperándote’, came out better than expected. Recently having done an album with Iglesias in L.A., I knew what a modern studio recording was supposed to sound like, production-wise. Nearly 200,000 copies were sold – and nobody was more surprised than us, especially when some of our fans from the sixties told us their daughter had returned home with our album, telling them how they had discovered these great new artists called the Dúo Dinámico. New! Just incredible…”

Two years on, the Dúo released another new album, ‘En forma’, which contained the hit success ‘Resistiré’ (= I will resist). In 1990, this song was included in Pedro Almodóvar’s film ‘¡Átame!’ (1990); thirty years later, during the Coronavirus lockdown, it became the unofficial hymn encouraging the Spanish people to continue demonstrating their resolve in the face of the epidemic. The Dúo Dinámico have remained in business until today, recording several more albums and even experiencing the honour a musical being staged with their own songs taking centre-stage: ‘Quisiera ser’ (2007). In 2014, Ramón Arcusa and Manuel de la Calva received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Latin Grammys in Las Vegas.

Looking back on the long (over sixty years!), fruitful partnership he has had with De la Calva, Arcusa analyses, “Surely, everyone knows that Manolo and I are different. Very different; we are like water and fire. Nevertheless, we are still friends, almost brothers, but taste-wise, we agree on very little, except for one thing: music. Being an extravert by character, Manolo is the soul of the Dúo on stage. He’s able to share his emotions with the audience completely. Me, less so. I am always thinking of the sound, the monitors, the backing musicians; is everything going well? This, sometimes, gives me a worried look, now even more so than in the days of old."

"Our relationship has been extraordinary, we’ve been together in this career of ours, although, secretly, there always was this hint of competition between the two. This has undoubtedly helped bringing out the best in both of us, especially as authors and singers. Few people are aware that, although most of our songs were signed by both of us, they were originally written by Manolo or by myself. Obviously, we have always worked on each other’s ideas or suggestions to improve on any song written by somebody else if we happened to stumble upon it. Sometimes, people ask us how we’ve endured sixty years together, while we saw other groups break up, start infighting, ending their careers ignominiously. Well, it’s very easy. First, always respect one another, and second… success. Success unites; failure divides and destroys what has been built.”

EUROVISION SONG CONTEST

Ramón Arcusa conducted the Eurovision orchestra on one occasion only, in 1978, but he was involved in the Eurovision Song Contest several times in other capacities. To begin with, in 1965, as part of the Dúo Dinámico with Manuel de la Calva, he took part in the Spanish pre-selection, which was held in Barcelona. With their self-penned song ‘Esos ojitos negros’, they just missed out on the ticket to the international final, however, finishing second behind Conchita Bautista’s ‘¡Qué bueno, qué bueno!’ .

Three years later, Arcusa and De la Calva were responsible for writing the song that brought Spain its first Eurovision victory: ‘La, la, la’, interpreted by Massiel. The story behind the tune is complicated and very interesting indeed. Arcusa vividly remembers the songwriting process. The scene is set in the small provincial town of Ourense in Galicia, where the Dúo Dinámico had performed the evening before. Due to a snowstorm, Manuel, Ramón, and their crew found themselves locked in their hotel, where there was little left for them to do but play card-games and wait for better weather conditions.

“While we were playing a game of Rummy,” Arcusa recounts, “Manolo whistled a little tune. Because I liked it, I tried to remember the sequence of notes, “Mi... fa-sol-sol... / fa-mi-re... mi-fa-fa... / do-re-mi-mi... re-re-do...si...”. When the game was over, I suggested, “Why don’t we go to the dressing room to rehearse for a bit?” Our guitar was still in the auditorium where we had performed the night before, so that’s where we went. Taking the notes that Manolo had whistled as a starting point, I sketched some harmonies which I thought were interesting: “Manolo, what about this!” He didn’t remember, but he did when we started playing them. And it sounded good. That day, we finished the melody of the chorus of what would turn out to be the Eurovision winner that following spring. After rehearsing it some 100 times to memorise the melody, we returned to the hotel."

"Two days later, we were due to travel to Belgium to perform for the Spanish émigré community, but we had to cancel the trip. The truth is that, although we didn’t get to Brussels due to the snow, this was a providential intervention from above, since otherwise we would never have composed ‘La, la, la’. A couple of weeks later, we finished the music. As a rule, we always allowed our initial ideas some time to mature. Manolo added the stanzas which, due to a key-change from major to minor, considerably improved the theme, while they gave it a distinctly Spanish, Andalusian, flavour at the same time.”

In January 1968, José María Lasso de la Vega, the duo’s manager, asked his protégés if they had any songs ready which would be suitable to submit to the Eurovision committee of Spanish national broadcaster TVE, who were about to pick the country’s festival entry in an internal selection. Listening to the melody which the boys played for him, Lasso agreed it had the potential to be a good Eurovision entry, but… there were no lyrics yet. Lasso suggested asking Joan Manuel Serrat, an up-and-coming singer-songwriter from Barcelona, to add the words and to also perform it on the Eurovision stage. Ramón and Manuel instantly fell for the idea, as Joan Manuel was a friend of theirs and they were keen to help him extending his reputation beyond the region of Catalonia. Invited to come and listen to the melody, Serrat liked it and accepted the proposal, including Manolo and Ramón only condition of sticking to simply la, la, la, la… in the chorus to make the sound as accessible as possible to an international audience. However, on the evening before the submission deadline, there was still no sign of Serrat or his lyrics.

“That night, Manolo improvised lyrics for the verses," Arcusa recalls, "which, as we then presumed, were only provisional, and which we would be happy to have replaced afterwards by Joan Manuel’s version if the song were to be chosen. We recorded a demo. At eight o’clock in the morning, we handed in the tape at TVE personally – just in time. That same day, the expert jury met to select the best song for Eurovision. From all submissions, our ‘La, la, la’ was chosen unanimously. We’re making progress! We’ve now got our song, with our lyrics and music, but Serrat still hasn’t written lyrics in Spanish, as we had asked him, though he comes up with a wonderful version in Catalan. Joan Manuel turned out to have two record deals: one with Edigsa Editions in Barcelona for his Catalan repertoire, and a second for his Spanish output, with a company based in Madrid, Zafiro. Together, all of us travelled to Milan, where both versions were recorded. The arrangement was taken care of by nobody less than Bert Kaempfert, the composer of Frank Sinatra’s ‘Strangers in the night’ – thanks to an intervention by Bert’s friend Artur Kaps, who was in charge of Eurovision at TVE.”

Convinced of the potential of ‘their’ song, record company Zafiro put the money on the table for Joan Manuel Serrat to go on a promotional tour across Europe, singing his entry in radio and television programmes in several other participating countries. Several weeks passed. Suddenly, from Paris, Serrat sent an open letter to TVE stating that he was only willing to sing ‘La, la, la’ in the Eurovision Song Contest in London if given permission to perform it in the Catalan language. Predictably, TVE was appalled Serrat’s unilateral statement, referring to his letter as blackmail. Manuel de la Calva and Ramón Arcusa were not feeling over the moon either. Without prior consultation, Serrat faced them with a fait accompli. Years later, Serrat said he stood up to the repression exerted by TVE and Spanish authorities, but, in his memoirs, Arcusa sheds a different light on the matter.

“Neither the Catalan language nor Catalan culture in general were repressed to the extent claimed by Joan Manuel. Moreover, in the specific (Catalan nationalist – BT) environment that he frequented, the shadow of censorship was felt more heavily than elsewhere, or it was perused to boast a certain level of victimhood or… on a strictly political level, activists were looking for a way to provoke a confrontation with the Franco regime on such a petty subject, because the subject of the quarrel was… our song. Or perhaps, Joan Manuel didn’t like the idea of representing the regime’s television station on an international stage. Who knows, maybe he just didn’t feel comfortable with the song, for reasons we’ll never know. It’s true that, afterwards, representatives of the regime, including Spanish television, didn’t treat Joan Manuel courteously. For this reason, we were on the phone with him every night – we in Madrid, he in Paris –, telling him about everything that was being said or published. Predictably, the criticism of him (in Spanish state media – BT) lasted for several weeks. We always defended him, as we felt that it had been his personal choice.”

Following Serrat’s demarche, TVE instantly took the decision to have him replaced. “Juan José Rosón, who was the general director of TVE at the time, called Manolo and myself to his office, commenting on what he felt was the impropriety of Serrat’s attitude – we didn’t know anything else about Joan Manuel’s considerations other than what was told on television – and he blandly told us to remain on standby, as we may be appointed to represent Spain ourselves. Manolo and I looked at each other in disbelief, because life seemed to be handing us another opportunity, which was rather necessary at this point in our career which had been on the wane for a while. Well… it wasn’t a weird idea: after all, we were the authors and, what’s more, we were professional singers."

"Everything seemed to be sorted out, it all made sense, but then, suddenly, Serrat’s Spanish-language record company, Zafiro, threw themselves into the fray, demanding that an artist from their catalogue should be chosen as replacement. They reasoned that they had already spent so much money that it would be unfair if another company walked away with the laurels if we won. Sensitive to their argument, TVE agreed; thereupon, Zafiro put forward Massiel, who happened to be touring in Mexico at the time. Returning to Spain with the first possible flight, she hurried into the recording studio with us and Juan Carlos Calderón, who helped us to adapt the arrangement to suit her key and… we were ready to go.”

According to some sources (listed below this article), Rafael Ibarbia, TVE’s staff conductor who joined Massiel and the songwriters at the 1968 Eurovision Song Contest in London’s Royal Albert Hall as the musical director, also played a role in creating the final version of the arrangement, either by writing the version for Massiel or by speeding up the tempo in order to stay within the three-minute deadline.

Arcusa emphatically denies this, “No, that’s bullshit! The great original version was done by Bert Kaempfert, who wrote it in Ab, the key suiting Joan Manuel’s voice. When Massiel was chosen to go to London, the score had to be transposed to Massiel’s C. At the request of TVE, Juan Carlos Calderón took care of this. Frankly, this transposing job could have been done by any music copyist, but TVE didn’t want to take any chances and picked an expert arranger. After all, more eyes see more. Rafael Ibarbia used this same arrangement in London. We knew perfectly well that one of the rules for any participating song was that it couldn’t be longer than three minutes. This certainly wasn’t something that had to be pointed out to us or our conductor in London. I never noticed anything in London that was different from Kaempfert’s original version other than the key tone."

"Ibarbia was the broadcaster’s main conductor, who led the orchestra for many music programs. As the Dúo Dinámico, Manolo and I regularly performed in television shows backed up by his orchestra. Like us, he came from Catalonia and, on a personal level, he was very accessible. As far as I remember, nobody else was considered for the conducting job in London. Everything had been sorted out: the song, the arrangement, and the singer… and Ibarbia was a solid conductor. There was no problem at all.”

Posing for the cameras with the Eurovision winner’s medals, from left to right: Manuel de la Calva, runner up Cliff Richard, Massiel, and Ramón Arcusa

“Attending all rehearsals, we saw more and more positive signs. Beforehand, we’d already heard that the expectations were good for our entry, but in London’s Royal Albert Hall, the outlook became even better. The musicians of the Festival Orchestra cheered our song in rehearsals and predicted that it would win ahead of their compatriot, none other than Cliff Richard and his ‘Congratulations’. That’s what’s called British phlegm! The orchestra played extraordinarily well for our song: we didn’t expect anything less from English musicians. During the concert, Manolo and I were in a boot on the left-hand side of the stage – no, not backstage. We have always been very pragmatic and we were happy being there among the audience. We expected a good result and I don’t remember feeling nervous.”

“When we won, it obviously was a proud moment for me as a songwriter – in the same way as I was immensely proud when my composition ‘Soy un truhan, soy un señor’ for Julio Iglesias was a number-one hit in 1977. For the career of Manolo and myself, it was good to get the publicity – and it kept us going for about a year, but not much longer. It didn’t impact our career in a fantastic way. The next Dúo Dinámico album sold miserably. Funnily, it was recorded in London, and even though it was two years after that glorious moment in the Royal Albert Hall, some of the musicians and staff in the studio still remembered us. That was a really special moment!”

“Back in Spain, that Eurovision win in 1968 was celebrated as if we had won a battle against the Royal Navy. Finally, we had our revenge from the inglorious defeat of the Spanish Armada, and in English waters! As a country, Spain was badly in need of an upsurge; I like to think that our ‘La, la, la’ contributed in bringing it about. Afterwards, somehow, there was a quarrel between Massiel and us, because, although we recognised her contribution to the success, we didn’t want to forget what had been brought about by the person who had promoted the song throughout Europe, Joan Manuel Serrat. But all of this has long been forgiven and forgotten."

"More than sixty versions have been recorded of our ‘La, la, la’ in every language imaginable, with some of the best singers and orchestras, ranging from Franck Pourcel to a charming interpretation by Amália Rodrigues. Even Filippo Carletti recorded it! For Manolo and me, the song has remained important until today, as there are many occasions when the 1968 Eurovision Song Contest is remembered in some way on radio or TV. On each of those occasions, they play the song again!”

Manuel de la Calva (left) and Ramón Arcusa being hailed in Madrid after their Eurovision win in 1968 with Massiel and ‘La, la, la’

Four years later, in 1972, Spain was represented in the Eurovision Song Contest by the magnificent crooner Jaime Morey. As in 1968, the song was picked by TVE in an internal selection. In the end, the melody chosen was a ballad called ‘Amanece’, with lyrics by Ramón Arcusa, whilst the music and arrangement were taken care of by the famous and influential film composer and television conductor Augusto Algueró.

“One day,” Ramón recalls, “Augusto Algueró called me, asking me if I wanted to do the lyrics for a composition he had written and which, in all probability, would be the Spanish entry for the Eurovision Song Contest. He played the tune to me and gave me a cassette with the piano part and the melody. At the same time, he told me he had commissioned three other lyricists to write a version as well. One of them was Antonio Guijarro, with whom Augusto wrote dozens of successful songs (including ‘Estando contigo’ for Conchita Bautista in 1961, Spain’s first-ever Eurovision contribution – BT). Augusto himself would pick the one he felt was most suitable. I decided to give it a try.”

“Let me be honest; I feel that this melody was not among Augusto’s best. He perhaps made the song a little complicated on purpose, adding more harmonies to prove his excellent musicianship. The verses weren’t easy, but the chorus was OK. Anyway, I allowed myself to be inspired by his music. Once I had the title in place, the rest of the words flowed from that. Did I like the result? Well, I’m not enormously proud of those lyrics, but, still, Augusto picked my piece of work. It wasn’t the first time I worked with him. In the early years of the Dúo Dinámico, he wrote an arrangement for us, ‘El tercer hombre’, because the song was published by his father’s company. His father also published some of our compositions for the film ‘Búsqueme a esa chica’. They were both Catalans; so we spoke the same language, which helped creating mutual trust. We had a very natural friendship with Augusto, let’s say: in a professional way. Though I felt ‘Amanece’ wasn’t particularly good, I’d like to stress that Augusto Algueró was a great musician, author, and arranger.”

At the 1972 Eurovision Song Contest in Edinburgh, won by Vicky Leandros’ ‘Après toi’ on behalf of Luxembourg, Jaime Morey’s interpretation of ‘Amanece’ finished tenth among eighteen competing entries. Naturally, Augusto Algueró conducted the orchestra for the Spanish entry. Ramón Arcusa and his English wife Shura were in the audience in the Usher Hall.

“I had never been to Scotland before,” Ramón reminisces, “and we had a great time. I remember trying a glass of real scotch back in our hotel. Jaime Morey was a friend of ours like Augusto. We had regularly met him backstage at music events in which we were both involved. He was kind of a modern crooner, very solid, and I think he defended the song very well. Listening to it now, I prefer the way he sang it on record, especially in the verses. Unfortunately, the sound mix in the television broadcast was awful. Thinking back, I cannot remember we were disappointed finishing tenth. In fact, I was rather happy with it. It was a respectable result – unthinkable today with all those songs from the Nordic and Baltic countries taking part. Augusto didn’t really need a Eurovision success to prove his mettle. He was already a crack in the Spanish music scene, and having his song picked to represent the country in the Eurovision Song Contest was just new proof that he belonged to the top of our country’s music business.”

In the 1978 Eurovision Song Contest, Spain was represented by Canarian singer José Vélez, who performed a love song wrapped in a waltz melody – a surprising rhythm for a Spanish entry – called ‘Bailemos un vals’ (= Let’s dance a waltz). According to the official credits, the song was co-written by Manuel de la Calva and Ramón Arcusa, who, at that time, were working separately as music producers, but still collaborated as songwriters regularly. “Honestly,” Arcusa admits, “this song was written by Manolo. Throughout our career, the two of us have shared our compositions. His songs were also mine, and mine were his. In this case, he wrote the music and the lyrics, and I wrote the orchestral arrangement. I really loved that song. As usual, Manolo had thought of a huge gimmick when writing it: a catchphrase in French, ‘Voulez-vous danser avec moi?’… really clever since the festival was held in France that year.”

In Paris, Ramón Arcusa conducted the festival orchestra himself – a surprise perhaps for those who only remembered him as one of the guys of the Dúo Dinámico. Few people knew, though, that Ramón had already written most of the arrangements for the Dúo Dinámico from 1966 onwards, and, once he took up working as a music producer in 1972, he had slowly become more confident writing more intricate orchestrations – but did he feel comfortable conducting an orchestra?

“It was a gradual thing,” Ramón explains. “In the early 1970s, we were already used to recording the scores for the various orchestral sections separately: rhythm, brass, strings, the backing vocals, etcetera, so I didn’t need to conduct large groups of musicians simultaneously. In those years, I quickly learnt my trade, writing dozens of arrangements and conducting groups of musicians in recording sessions. In 1977, I probably had my first experience with a big orchestra when I conducted a guest performance by ‘my’ artist Manolo Otero at the Viña del Mar Song Festival in Chile. Later that same year, I recorded my first album with Julio Iglesias, ‘A mis 33 años’, which was done with full string and brass sections as well as a woodwind group, a choir of six, and of course a rhythm section. Some of the session musicians were surprised to see me conducting. Following that recording, I conducted the orchestra in a television show with Julio as well.”

“Around that time, at the premises of the SGAE (the Spanish Association for Composers, Authors, and Music Publishers – BT), I happened to bump into the great musician Antón García Abril (a renowned composer of serious music and film soundtracks – BT), who told me he had seen me on television. According to him, I conducted the orchestra and moved my arms like nobody else! He thought I did an excellent job. At first, I wasn’t sure if he was being serious, but he was – so I said, “Thank you very much!” It’s the best compliment I have ever been given. Not bad for someone who never studied conducting."

"Perhaps I intuitively learnt how to move my arms when conducting the church choir at the catholic school. The role was given to me as I was the only boy able to read the score. We took on some demanding pieces, such as the ‘Ave María’ composed by Tomás Luis de Victoria, a masterpiece. On the other hand, we also sang Gregorian pieces. There’s no type of music in which more gesticulation is required from the conductor than in Gregorian chants, so maybe this experience had helped me learning about the conducting lines. Frankly, though, if you ask me, I don’t have a clue if those lines should be twisted or zigzag! To cut a long story short, I wasn’t feeling nervous at all about conducting the Eurovision orchestra in Paris. I was sure about the arrangement I had written, while I had enough experience by then to guide the musicians through the score professionally.”

Picture postcard of José Vélez during rehearsals at the 1978 Eurovision Song Contest in Paris, with Ramón Arcusa behind him conducting the orchestra

At Paris’ Palais des Congrès, ‘Bailemos un vals’ received a total of 65 votes from the international jurors, finishing ninth among twenty competing songs.

“That week in Paris was flawless,” Ramón comments. “The French had put together a fine orchestra, probably with the best musicians available: after all, you don’t go on a date without looking your best. In the rehearsals, we didn’t have any notable problems. Manolo was José Vélez’s record producer and he looked after him. We always got on well with our artists. Artists need your help and they don’t want discussions and negativity. We made sure everything was easy and smooth. José performed the song with passion, which made us proudly happy. In France, the song caught on – afterwards, a French advertisement company even used it for a television commercial. It was nice to conduct the Eurovision orchestra, but I cannot say it made me feel particularly proud. Lots of things occurred in the course of my career, and this was one of them. I took life as it came and was always happy when opportunities like this came my way.”

After 1978, and three Eurovision participations, Ramón Arcusa did not return to the competition. What does he think of the way the contest has evolved?

“The Eurovision Song Contest is now a festival of lights and colours: of course, music is a necessary element, but it seems to come in second place. Watching the programme, one cannot escape the impression that the producer of each and every song has been trying to invent the most exciting or exotic presentation. In this setup, the song itself seems less important. When television as a medium was less developed, music itself took centre stage. Progressively, due to developments in the world of television, live music has been suffering, and so have the musicians.”

OTHER ARTISTS ABOUT RAMÓN ARCUSA

So far, we have not gathered comments of other artists about Ramón Arcusa.

Ramón Arcusa’s memoirs, published in 2020

EUROVISION INVOLVEMENT YEAR BY YEAR

Country – Spain

Song title – "La, la, la"

Rendition – Massiel

Lyrics – Ramón Arcusa / Manuel de la Calva

Composition – Ramón Arcusa / Manuel de la Calva

Studio arrangement – Bert Kaempfert / Juan Carlos Calderón

Live orchestration – Bert Kaempfert / Juan Carlos Calderón /

Conductor – Rafael Ibarbia

Score – 1st place (29 votes)

Country – Spain

Song title – "Amanece"

Rendition – Jaime Morey

Lyrics – Ramón Arcusa

Composition – Augusto Algueró

Studio arrangement – Augusto Algueró

Live orchestration – Augusto Algueró

Conductor – Augusto Algueró

Score – 10th place (83 votes)

Country – Spain

Song title – "Bailemos un vals"

Rendition – José Vélez

Lyrics – Ramón Arcusa / Manuel de la Calva

Composition – Ramón Arcusa / Manuel de la Calva

Studio arrangement – Ramón Arcusa

Live orchestration – Ramón Arcusa

Conductor – Ramón Arcusa

Score – 9th place (65 votes)

SOURCES & LINKS

- Ramón Arcusa’s entertaining and very well-written memoirs: 'Soy un truhan, soy un señor’, ed. MR: Barcelona, 2020

- Bas Tukker had an extended email exchange with Mr Arcusa in July and August 2020, discussing various parts and aspects of the latter’s career in music

- Two online articles claiming Rafael Ibarbia rewrote the arrangement for ‘La, la, la’ prior to the Eurovision Song Contest in London, which can be accessed by clicking this link and this link

- Photos courtesy of Ramón Arcusa & Ferry van der Zant

- Thanks to Edwin van Gorp for proofreading the manuscript

WEBSITE

%20(Shura%20Hall).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment