The following article is an overview of the career of French arranger Pierre Chiffre. The main source of information is an interview with Pierre Chiffre, conducted by Serge Elhaïk in 2016. The article below is subdivided into two main parts; a general career overview (part 3) and a part dedicated to Pierre Chiffre's Eurovision involvement (part 4).

Contents

- Passport

- Short Eurovision record

- Biography

- Eurovision Song Contest

- Other artists about Pierre Chiffre

- Eurovision involvement year by year

- Sources & links

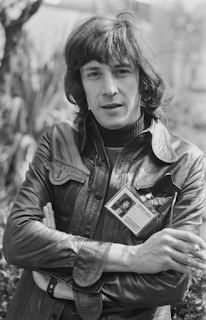

PASSPORT

Born: March 21st, 1948, Gabarret (France)

Nationality: French

SHORT EUROVISION RECORD

Pierre Chiffre, who had a short career as an arranger and conductor in Paris’ recording studios in the first half of the 1970s, led the orchestra in the 1974 Eurovision Song Contest, conducting his own arrangement to ‘Fleur de liberté’, that year’s Belgian entry performed by Jacques Hustin.

BIOGRAPHY

Pierre Chiffre was born in a village about halfway between Bordeaux and Toulouse in Southern France. He grew up in a family in which both parents were avid amateur musicians. “In her young years, my mother had tried to become a professional singer, but in the end, she had learnt to play the piano instead. In fact, her sister was an opera singer for a while, but she had to stop due to familial reasons. As for my father, he was a tax collector, but he loved playing the piano as well. His mother was Russian and I think his Slavic genes gave him his musicality. From age five onwards, for some eight or nine years, I had the privilege of studying solfege and the piano with several private teachers. Now, my father, who besides his daytime job spent a lot of time and energy on organising summer festivals in villages across the region, had once met Édouard Duleu (an accordion player enjoying nationwide fame in France – BT) at one of those occasions; thanks to my father’s intervention, I was allowed to play the accordion on stage at Duleu’s side at several of those festivals. An accordion had been given to me as a present by my parents – and in fact after a while I could manage quite well playing it in a self-taught way. In spite of myself, I became the petite vedette of the village and the wider surroundings, also performing at local school parties now and again.”

“We moved to Aire-sur-l’Adour (some 50 km south of Pierre’s native Gabarret – BT) when I was ten years old – and some time later, in my adolescence, when I was about fourteen, I developed an ever-increasing passion for forming all kinds of little rock groups with my classmates. We founded a band with three or four elements… piano, guitar, bass, and drums, playing rock and what is referred to as pop nowadays. Around the same time, I began composing music for some songs here and there. Despite this, I never followed any conservatory course, which made me a true autodidact when I turned to working as an arranger and conductor later on.”

“In 1965, when my father retired, the family moved to Bordeaux. This was great for me, as it allowed me to get to know a whole bunch of young people who played in all kinds of different music groups who toured the region. Of my peers, I was the only pianist, for all the others had chosen guitar, bass, or drums. By that time, I had said goodbye to my accordion, in part due to my musical tastes which had changed, but also because I needed the money to buy myself a portable electric piano. It allowed me to join a band which I had met. Fortunately, my parents also sponsored me a little to buy that piano, but only on the condition that I would continue my studies at the lycée in Bordeaux. They were keen for me to embrace a liberal profession, never really taking my passion for music entirely seriously. With our band, we didn’t have that many professional engagements, playing occasionally in nightclubs and in joint performances with ballroom orchestras.”

“One day, a musician approached me to ask if I was interested in joining Eddy Harrison’s ballroom orchestra for dancing galas. I accepted, even though I was just seventeen, with all the other orchestra members being three to eight years my senior. At this point, my parents decided to keep a more watchful eye on me, since Harrison’s orchestra sometimes performed in venues further away from Bordeaux. This all went rather well until, one day, a better-known bandleader, Jean Bernard, who was an accordionist and trombone player, gave our orchestra an offer we couldn’t refuse. He was particularly interested in our rhythm group. Bernard’s ensemble had a small brass section – and he performed at all kinds of occasions, bals musette and other large festivals. As Bernard took over our entire orchestra, we effectively merged two bands into one. This made us one of the two or three most sought-after orchestras in the Bordelais, the region around Bordeaux.”

“Already in the days with Eddy Harrison, I was the orchestra’s arranger, quite simply because I was the only one in the band who knew anything about solfege. I wrote for a limited number of musicians; a rhythm group and one saxophone, sometimes with one additional trumpet. When Jean Bernard became our bandleader, he asked me to write dozens and dozens of arrangements for his orchestra of up to twelve elements with three vocalists able to handle different styles – including one black guy who sang rhythm-and-blues. Every week, I penned four or five arrangements of songs which were in the charts at that time. Because I really wanted to get into things seriously, I had taken out a loan to buy myself a Hammond organ.”

“Finding myself unable to combine school with my activities as a musician, I quit the lycée mere months before the final exams. To appease my parents, I enrolled at Bordeaux’s high school to obtain a law degree. This was a two-year course which didn’t require any prior diploma. Moreover, the lessons only took up two hours a day – and not even every day. In between courses, I sometimes attended jazz concerts which took place at Bordeaux’s local radio station. There I met a drummer who became a friend; we decided to sit together each morning for one hour to study solfege. This guy knew his way around in the world of jazz, and with him and one other, I formed a jazz trio with Hammond organ, drums, and guitar. Part of our repertoire were contemporary hits which we interpreted the way we liked them. We didn’t perform that much; just some touring in the summer now and then. We also worked in nightclubs in and around Bordeaux, while I continued touring with the ballroom orchestra during weekends.”

“Meanwhile, I also continued trying to write the occasional song. Some people I got to know wondered if I wanted to put their lyrics to music. When I had passed the exam required to join Sacem (France’s music copyright organisation – BT), there was the requirement of submitting the names of two musicians who supported your membership request. Well, those two were – first my father’s old friend, Édouard Duleu, the accordionist, and then one of Duleu’s friends… none other than Raymond Lefèvre!”

“Another friend of mine from Bordeaux, Bernard Saint-Paul, worked as an artists’ impresario at the time, contracting English bands to perform in nightclubs across the Bordelais. One day, he told me he’d love to record some of the songs I’d composed with one of those overseas groups. I had just finished the music to one of Bernard’s lyrics. Shortly after those sessions, Bernard left for Paris to become Adamo’s artistic director. Later on, he also started working with Gilbert Montagné and Véronique Sanson. It wasn’t very long after he had left when he called me. It was in the fall of 1968. “Pierre, Adamo is coming down to Bordeaux for a gig. He has a support act performing the part of the show before the break, a young artist who has just made his debut. It would be interesting if you get in touch with him, because we have to form an orchestra to accompany him.” It turned out that youngster was Julien Clerc! Bernard Saint-Paul had told him I wrote arrangements for a local orchestra and that I was good at my job.”

“That night, Julien told me, “Listen to my performance in the first part of the show and we’ll discuss it afterwards.” His performance struck me like a lightning bolt. My lord, what a great performance! His set consisted of merely three songs, all coming from his first two singles, ‘La cavalerie’, ‘Jivaro song’, and ‘Ivanovitch’. Later that night, in a conversation, Julien explained to me what kind of accompaniment he was looking for, “but,” he added, “at the moment I don’t have the means to hire a group of musicians. I’m looking for a conductor, someone who joins me to look after the musical accompaniment, working with local musicians wherever we come to do a show.” He finished by saying, “My next record is due to be released next February on Europe N° 1 (a popular radio station – BT). Let’s meet on that and that day at the entrance of the radio station, at half past eleven.” Now, imagine, this appointment was three months away! I was astonished that anyone was organised enough to plan a meeting like this.”

Jacqueline Taïeb’s single ‘Bonjour Brésil’ (1969), one of Pierre Chiffre’s first feats as a studio arranger

“Anyhow, I had to part ways with my ballroom orchestra and also with my family. I had to settle in Paris! I was still in touch with Bernard Saint-Paul who told me in December 1968, “Come over here and then we’ll see if we can sell your compositions.” He had booked a room for me in a small hotel at the Rue Saint-André-des-Arts and introduced me to some Parisian music publishers – and in fact they bought one or two songs from me. Suddenly, I was immersing myself in Paris and everything it stood for… it was an overwhelming experience.”

“Finally, in February 1969, I went to Rue François Ier where Europe N° 1 studios were. On the pavement, there’s this big bloke, wearing the fur coat he was famous for back in those days. He shakes hands with me, we enter the building, finding our way up into the studio. After the presentation of his new record, ‘La Californie’, we had a little chat and he said, “I’ve got some good news; next month we will be the support act for Gilbert Bécaud’s concerts in the Olympia Hall.” Incredibly, my first job in Paris was to coordinate Julien Clerc’s performance with the Olympia’s regular orchestra. We rehearsed the performance in the Ancienne Belgique, a concert hall in Brussels, where I led a band of four musicians while seated at a superb Hammond organ. In the Olympia, and subsequently on tour, I had the opportunity to witness Gilbert Bécaud at work, a great personality who played all kinds of tricks on me. At the time, my hair was rather long and I was wearing Ray Charles-type spectacles. Bécaud liked nothing better than wearing a wig and then nicking the spectacles from my dressing room. His bandleader Raymond Bernard, the regular conductor of the Olympia orchestra, told me, “Well, nobody knows the tempo of Julien’s songs better than you do, so obviously you’ll conduct the orchestra for his part of the show.” Of course, someone like him showing such confidence in me was fantastic.”

“Being Julien Clerc’s bandleader was a big plus for my own career, given how steep his path to the top of the entertainment ladder was. The guy was popular overnight. In the weeks following our performance at l’Olympia, Julien told me, “Now is the right time to form an orchestra of our own.” So that’s what I did, hitting the road to perform at all kinds of different galas with the musicians I had recruited. At the young age of 21, I had managed to get a foot in the door in the world of showbiz.”

“Around the time of that tour with Julien Clerc in 1969, Bernard Saint-Paul gave me the opportunity to work as a session player and also as an arranger. In the recording studio, I met a singer who called himself Marcellin, for whom I wrote the two arrangements to his first single release. It was the first time my name appeared on a record sleeve. I never asked myself if I had the ability to be a record arranger. I simply said, “Yes, I’ll do it.” Claude Benaya (a bass player – BT), who knew the studio business inside out, helped me out by bringing together a group of musicians for this session with Marcellin. Following that, again thanks to Bernard Saint-Paul, I recorded another single, this time with Jacqueline Taïeb. Of course I had never studied to be an arranger; therefore, for Marcellin’s songs, I simply used the formula of the orchestra I was used to write for in the Bordelais – those were the instruments I knew. I didn’t want to take too many risks working in the studio for the first time with musicians I didn’t know. At the same time, though, I decided to buy myself a book which detailed the range of every orchestral instrument. For the session with Jacqueline Taïeb I added one or two instruments to the set-up just to hear how that would sound. I was quick to realise what could be done with the means at one’s disposal in the professional recording studios.”

In those early days of Chiffre’s career as a studio arranger, he was fortunate to have rising star Julien Clerc as one of his guardian angels. In 1970, when Clerc recorded his second album ‘Des jours entiers à t’aimer’, Chiffre – essentially still a ‘nobody’ in Paris’ session world – had the opportunity to take care of one title, ‘Bourg-la-Reine’. “Without a shadow of a doubt, this was a favour Julien accorded me,” Chiffre comments, “and I remember how weird I felt standing in that studio at the side of Jean-Claude Petit, who wrote the majority of arrangements for that record.”

Julien Clerc taking centre-stage in the cast of the French staging of ‘Hair’ at Paris’ Théâtre Porte-Saint-Martin

During Clerc’s concert series in Olympia, the singer received an offer to play the lead role in the French staging of Hair, which would go on to be performed for two-and-a-half years at Théâtre Porte-Saint-Martin, Paris. The rock musical’s producer, Annie Fargue, and director Bertrand Castelli wanted Clerc’s conductor to sign on as well. “Of course I said yes,” Chiffre recalls. “They just said, “You’re Julien’s band leader, so we want you to be the band leader in Hair as well.” Apart from the rhythm group which accompanied Julien for his concerts, Claude Benaya found the other musicians for me, most notably the brass players and a percussionist. When the performances of Hair started, Julien was still having his tour as well – on the nights when he was performing in a solo concert, there was a replacement taking his part in Hair. I joined Julien, which meant Claude Benaya had to take over the band leadership in the theatre on those nights. At some point, Julien decided to abandon Hair, giving precedence to his solo career. The show continued, with Gérard Lenorman taking Julien’s part. Inevitably, Bertrand Castelli wanted me to choose; either continue to conduct Hair, or follow Julien. To tell you the truth, my daughter had just been born, it was in the spring of 1970 and I was beginning to be booked to write arrangements for several artists – I wasn’t particularly looking forward to going on the road any longer. That’s when I told Julien that I had decided not to come with him… to our mutual regret.”

When Hair stopped in 1972, Chiffre worked for one more year on another musical production, Godspell, which was staged in the same Parisian theatre. “The cast consisted of a group of young artists who were virtually or completely unknown at the time, like Dave, Armande Altaï, Daniel Auteuil, Michel Elias, and Grégory Ken. The orchestra I led was much smaller than in Hair – just four musicians. I played the piano and the organ, while the other band members were my good friends Christian Padovan, Gérard Kawczynski, and André Sitbon. With guys like this on board, we couldn’t be anything but successful! When Godspell stopped at the Porte-Saint-Martin, the show went on a tour across the country. Because I wanted to stay in Paris, Michel Bernholc replaced me. For his studio arrangements, Michel often used the same group of session players as I did.”

In that same period, Pierre Chiffre also composed a fully-fledged musical, ‘La nuit des temps’, but regrettably it never reached the stage. Meanwhile, Chiffre was ever more in demand as an arranger for pop artists. Notably, he added the scores to Gérard Palaprat’s first two albums, ‘Fais-moi un signe’ (1971) and ‘Vive la terre’ (1973). Chiffre first worked with Palaprat in ‘Hair’, where the singer performed one of the side roles.

“One night, while we were performing with Hair, I was approached by a guy named Patrick Lemaître. “You are an arranger, aren’t you?” he asked me, “and don’t you conduct Julien Clerc’s stage performances as well? Well, listen, with Maurice Vallet, I’m planning to write some songs for a record with Gérard Palaprat. We would like you to take care of the arrangements. I’ve got quite some ideas for the arrangements of my own songs as well.” That was in 1970 for ‘Les orgues de Berlin’, the single which kick-started Gérard’s solo career. I had some ideas myself as well, and following Claude Benaya’s suggestions I wrote a harp part for the intro of ‘Tristan des terres neuves’, the B-side of that same single. In the end, the recording was a real team effort with Patrick Lemaître and the session players. That’s one of the reasons why I thought of myself more as a conductor than an arranger. Another factor was that, when it came to writing technique, I never attained the level of certainty of my colleagues in the business… in fact, some of them were better than me by a country mile. When I was writing arrangements, my main ally wasn’t my knowledge of music, but my nerve, I would say. I just did it!”

“With Palaprat, we had one hit after the other. I remember ‘Fais-moi un signe’, also produced by Patrick Lemaître, a song for which the arrangement was a bit eccentric – rather Anglo-Saxon. ‘Pour la fin du monde’ was another notable success. Palaprat’s song ‘Dostoïevski’ was recorded live with Russian musicians who worked in the ‘Etoile de Moscou’ (a Russian restaurant in Paris – BT) – we had to do this live, because it was a song in which the melody followed the voice rather than the other way around. It took me considerable preparation time to get the hang of the balalaika. Obviously, I’d never written a balalaika arrangement in my life.”

Like his fellow arranger Michel Bernholc, Pierre Chiffre usually refrained from working with the most sought after group of session players in Paris, who more or less worked as a group – the so-called ‘requins’. Instead, he formed a group of his own with younger musicians. Chiffre, commenting, “Indeed, it was really important for me to form a rhythm group consisting of guys who got along well with each other and who produced a sound which was different from what the run-of-the-mill pop record sounded like in those days. There always was this band of four or five core musicians with me in the studio. For string and brass players, this was not the case – Jean-Claude Dubois usually assembled those players on my behalf.”

In the early 1970s, apart from his involvement with Gérard Palaprat, Chiffre also worked on arrangements for Alain Bashung, Claudia Alexandre, and France Gall’s brother Patrice. In 1972, he had the opportunity to write an arrangement for Johnny Hallyday, scoring his single release ‘Comme si je devais mourir demain’. “I owed that commission to Patrick Lemaître and Jean-Pierre Lang. For the recording, I didn’t work with my own set of musicians, but with Johnny’s rhythm players. All of this took place in London, which was a great experience; aged just 24, I found myself working in the same studio the Rolling Stones used for their recordings! That session for Hallyday was really out of this world, as I was lucky enough to have at my disposal a group of twenty local string players who really swinged. A swinging string arrangement wasn’t something which one could expect to accomplish easily with French musicians back then.”

“One of the main producers of Barclay Records, Philippe Monet, took a malevolent delight in introducing me to others as the frontrunner of a whole new generation of arrangers. Certain producers who understood what I was doing, specifically asked for the ‘Equipe à Chiffre’ for their sessions. I employed the recording techniques I knew so well from my experience of working with rhythm groups in smaller studios – studios which were mostly in demand for demos, not for full-fledged recordings. I was looking to create a sound which was flatter, more Anglo-Saxon; the type of sound I had discovered when recording the orchestra for Johnny Hallyday in the Olympic Studios (in London – BT).”

Astonishingly, given his success as a studio arranger, Pierre Chiffre left Paris and his career there behind in 1975, withdrawing to the southwestern part of France where he had grown up. “Don’t forget my Parisian career had developed more or less by accident,” Chiffre explains. “I never put pressure to make it there; it just happened. Looking back I consider it a wonderful human adventure. I experienced that period in an incredible way – so incredible, in fact, that I couldn’t imagine continuing my work in the music industry if conditions were to change radically from those I was used to. When I noticed this would be impossible, I took the decision to stop. This was a matter of character, because I sensed the metier was about to change profoundly, but also for private reasons. Moreover Paris simply wasn’t my cup of tea.”

“I retraced my steps, moving back to Bordeaux. There I joined TH Marcus, a local pop-rock band. At the time my desire was to get back onto the stage. We even recorded a single which was released at RCA in 1977, containing one title written by Gérard Palaprat, and the other by myself. Admittedly that record wasn’t really representative of the kind of music we usually played. Our band stayed together for two or three years before we each went our separate ways. Professionally, I went into business. My ambition was to combine sound and image. Those were the days of slide-films; with a friend in Bordeaux who was a professional photographer I produced several of such audio-visual productions.”

Occasionally, in the second half of the 1970s and early 1980s, Chiffre returned to Paris for studio projects with pop artists, including Philippe Richeux, Nathalie Corène, and Pascal Brehat. “That album with Brehat was a commission which came my way thanks to Jacques Poisson, a producer who I had stayed in touch with after leaving Paris. From time to time, Jacques and I met up somewhere in the vicinity of Bordeaux where he owned a seaside house. Together we loved conceiving all kinds of grand projects for the future. In 1986, four years after the album for Brehat, I wrote arrangements for a studio recording for the last time. This was for Désir – and I admit I felt disillusioned having to work in a studio not chosen by myself and with musicians which hadn’t been handpicked by me.”

“The owner of that studio was a singer, Jacky Reggan. By that time, he was earning a life organising concerts in large festival domes. Thanks to Jacky I met an engineer who had opened a shop in Paris focusing exclusively on music software and music interfaces. At the time, this was the only shop in Europe of its sort. The arrival of micro informatics enabled me to take the leap from music software applications to graphic applications, a much wider playing field. I worked in communication technology, making a career in it which lasted for years. At the moment (speaking in 2016 – BT), I’m living in the South of France where I withdrew after retiring from my profession. As for music, nowadays I only play when I feel like it. I undertook writing music for large church organs, but I haven’t had the opportunity yet to have those compositions performed. That’s something I like toying with in my mind…”

Pierre Chiffre in later years, after his withdrawal from the recording business

EUROVISION SONG CONTEST

Pierre Chiffre was involved in the Eurovision Song Contest as a conductor once, in 1974, at the tender age of 26, not representing his own country, France, but its northern neighbour Belgium. That year, Belgium was represented by one of Wallonia’s most popular solo artists, Jacques Hustin. Working with various co-authors, Hustin submitted six songs for a televised pre-selection, aired on January 14th, 1974, and hosted by legendary RTB speakerine Paule Herreman. For the arrangements, Hustin – or his record company – took the decision to turn to France; more specifically to Paris. The task of subdividing the six arrangements befell on artistic director Jacques Poisson, a good friend of Pierre Chiffre.

“One day, Jacques Poisson told me, “Jacques Hustin is a very popular singer in Belgium. He will be representing his country at the coming edition of Eurovision, but we don’t know yet which song he will be performing there. First we’re going to record six titles; I want you to write the arrangements to three of them – the three others will be taken care of by Christian Chevallier.” The sessions took place at the Studio d’Hérouville (a legendary recording studio situated in a chateau on the outskirts of Paris owned by film composer Michel Magne – BT) and when we were done, the recording tapes were sent to Belgium for the final choice. While working in those sessions with Chevallier, I was much impressed by his skilful handling of the string and choral parts. He was an ace at writing them. Afterwards, Jacques Poisson said, “And Christian Chevallier was impressed by your efficient way of working!”

“Some weeks later, I received a message from Jacques Poisson to the effect that of the six original titles, three had been eliminated – but the three songs left were all arranged by me! (‘Etranger, baladin, voyageur’, ‘Fleur de liberté’, and ‘On dit de toi, on dit de moi’ – BT) “So you’re sure of your ticket to Eurovision,” he said. In the end, ‘Fleur de liberté’ was chosen for the contest. The arrangement I had written for the record version had to be revised and modified for the orchestra of the BBC put in place for the show consisting of eighty elements.” (it is beyond my knowledge exactly how many musicians were in Ronnie Hazlehurst’s orchestra for the contest in 1974, but eighty seems a bit too generous – BT)

When asked about his memories of the international Eurovision final, held in Brighton, Chiffre comments, “One had to be there several days in advance of the actual broadcast. On the day of my departure for England, while packing my suitcase, I heard on the radio that Georges Pompidou had passed away (Pompidou being the president of France, who died on April 2nd, 1974 – BT). France, which had picked the singer Dani as its representative, withdrew as the contest was due to take place on April 6th, the day chosen for the president’s funeral. Upon my arrival in Brighton, I was asked to produce my passport at the hotel reception. The girl at the desk quickly noticed that it was a French pass. She told me there had to be some sort of misunderstanding, given that the French delegation for the Eurovision Song Contest had annulled all their bookings! I explained her that, even though I was French, I was part of Belgium’s delegation.”

“As for Jacques Hustin, he finished ninth, and I remember well how ABBA, the group from Sweden, came first with their song ‘Waterloo’. For them, it was the starting point of a marvellous career. In spite of everything, in spite of that ninth place, one Belgian newspaper put our performance on their front page the following Monday. The journalist commented to the effect that it was a good result, given how badly Belgian singers had done in previous years. They had regularly finished near the bottom of the scoreboard. As for my own contribution, taking part in Eurovision is a happy memory. Whichever way you look at it, the contest was some sort of an apogee in my career.”

Belgium’s Eurovision representative Jacques Hustin in Brighton’s Pavilion Gardens (1974)

OTHER ARTISTS ABOUT PIERRE CHIFFRE

So far, we have not gathered comments from other artists about Pierre Chiffre.

EUROVISION INVOLVEMENT YEAR BY YEAR

Country – Belgium

Song title – "Fleur de liberté"

Rendition – Jacques Hustin

Lyrics – Franck F. Gérald

Composition – Jacques Hustin

Studio arrangement – Pierre Chiffre

Live orchestration – Pierre Chiffre

Conductor – Pierre Chiffre

Score – 9th place (10 votes)

SOURCES & LINKS

- Thanks due to Serge Elhaïk, who allowed me to use the interview he did with Pierre Chiffre in 2016, the original of which can be found on pg. 459-70 in his monumental book about French arrangers: ‘Les arrangeurs de la chanson française’, Ed. Textuel: Paris, 2018

- A YouTube playlist of Pierre Chiffre’s music can be accessed by clicking this link

- Thanks to Joe Newman-Getzler and Edwin van Gorp for proofreading the manuscript

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment